AVPS Releases 2011 Holiday Card

29 December 2011

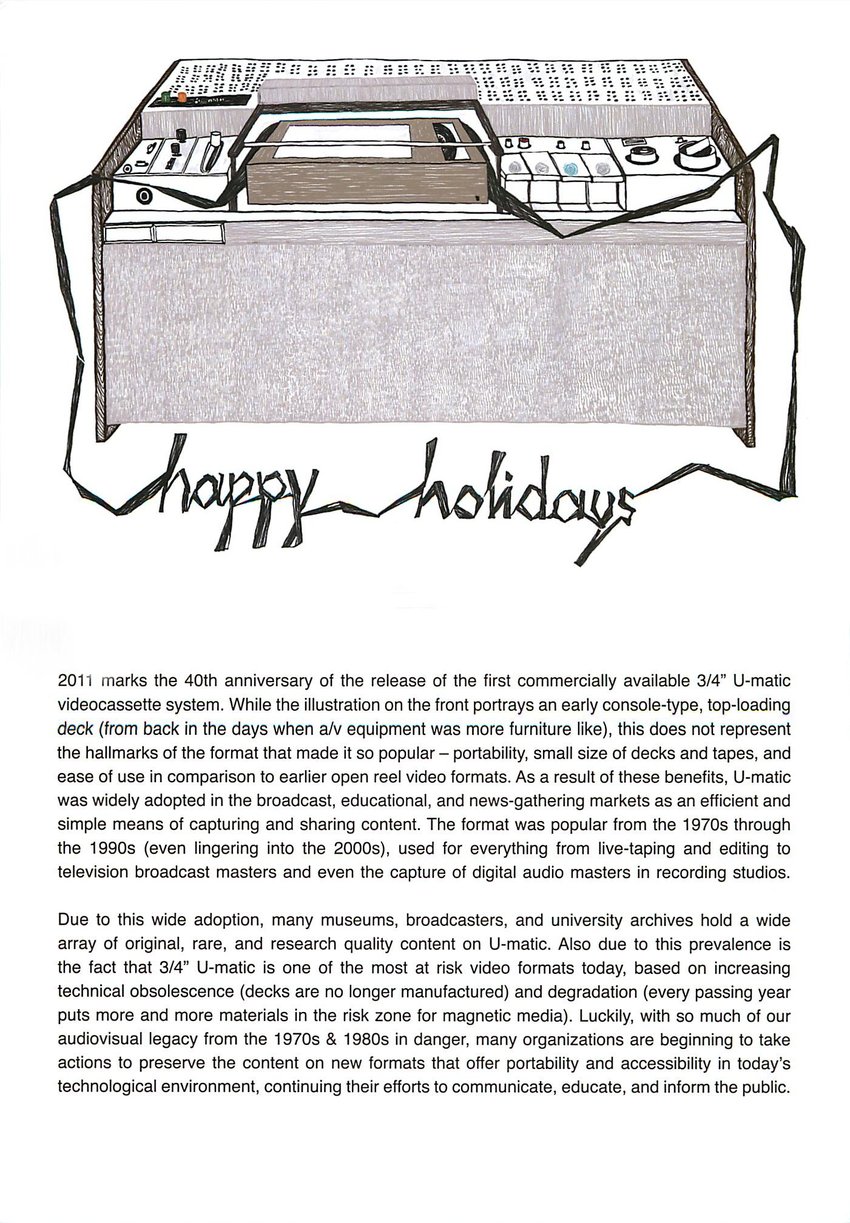

AudioVisual Preservation Solutions released its sixth annual original greeting card for the 2011 holiday season. This year’s card features an illustration of the first commercially available 3/4″ U-matic deck in commemoration of the 40th anniversary of its initial release to consumers and significance in the wider adoption of videotape beyond the television studio.

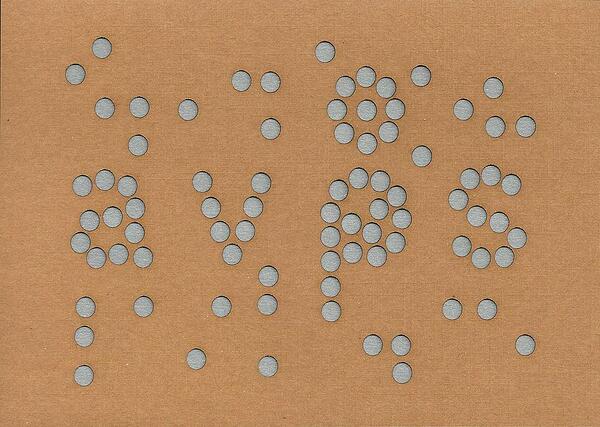

Also available for viewing now is the 2010 holiday card, which features a punch-hole design of the AVPS logo in recognition of the history of punch cards in the development of modern digital technologies.

As in past years, the cards are inspired by the field that we work in and its history. As audiovisual and digital media become a more ingrained part of society, we often forget the moments of origin or the amazing advancements they represented. The original art work is created by Stephanie Housley, a New York based artist/designer.

We are pleased to send these greetings to our clients and all of the other members of our community who are dedicated to the preservation of our audiovisual heritage. We are especially delighted to note that we often see the cards posted in the archives we work in long after the holiday season has ended.

2010 and 2011 Holiday Cards:

https://www.avpreserve.com/uncategorized/avps-holiday-cards-2010-2011/

2008 and 2009 Holiday Cards:

https://www.avpreserve.com/uncategorized/avps-holiday-cards-2008-09/

2006 and 2007 Holiday Cards:

https://www.avpreserve.com/uncategorized/avps-holiday-cards/

AVP Holiday Card – 2011

29 December 2011

Artwork by Stephanie Housley from Coral & Tusk

All Images on this page are copyright protected and may not be reproduced or used without permission from AudioVisual Preservation Solutions.

AVPS Holiday Cards 2010-2011

29 December 2011

All Images on this page are copyright protected and may not be reproduced or used without permission from AudioVisual Preservation Solutions.

Select links below to see a larger image with the full text

2010

2011 Archives Year In Review

28 December 2011

When the world ends next December, all of our blathering and fretting over the best way to preserve archival materials will prove to have been in vain. In spite of it all, we trundle ahead with our work like the Sisyphean hero. Normally, I imagine the hill decades or centuries long; if asked my opinion about a new movie or album or current event, I say ask me again in 50 years. But, considering the circumstances, the normal timeline needs accelerating. Thus, the 2011 Archives Year in Review.

Most Interesting Acquisition: Library of Congress to receive entire Twitter archive

Though easily mocked by Your Dad (Yes, Twitter is mostly banal content, but so are the journals and letters of the past that are considered important source materials today) this acquisition is important not only because of the snapshot it provides of everyday life and the way that technology affects or is adapted by society, but also because of the technological efforts required to ingest and preserve the collection. As LOC Digital Initiatives Program Manager Bill Lefurgy says in the article, the Library needs to develop guidelines and methodologies for how to accept and manage very large data sets in anticipation of future acquisitions. The Twitter data presents an excellent opportunity to collaborate with private industry on improved means for data transfer and preservation.

Most Appropriate Reaction to the Twitter Acquisition: Tweeted by @AlbertBrooks, “Damn. If I had known this I never would’ve done that one about my ass”

Most Archivally Philosophical Documentary: Knuckle

The argument over the best use of archival material in a documentary is a parlor game, no real answer but a playful way to show off one’s erudition and argue for argument’s sake. Instead I ask the question, when does source material become archival material? Ian Palmer’s Knuckle, a documentary about the tradition of bare-knuckle fighting to settle disputes among families in the Irish Traveller community, was videotaped periodically over 12 years before being crafted into a film. Palmer states that he put the tapes away in boxes and didn’t even know what the content was until reviewing it when production started. What defines an archive? Age? The way it’s stored? Frequency of access? Original intention for the materials? An original creator vs. a re-user of existing material?

Most Egregious Use of Archival Material in a Documentary: Flying Monsters 3D with David Attenborough

The 3D processes used in this film did not exist during the dinosaur age, so I can only assume that they used some crappy post-process conversion on the source footage. Very disappointing.

#waytotakeastand Award for Archives: Association for Recorded Sound Collections Copyright Committee

Many people don’t realize that audio recordings made prior to 1972 fall under state and not federal copyright law. This means that the same length of copyright, public domain applications, and Section 108 protections do not apply to audio recordings unless a state has modified its laws to mirror federal statutes. This is seldom the case, and as a result the access to pre-1923 works and the ability of libraries and archives to take care of such works has been severely limited. Since 2009, ARSC has been rattling cages in the federal government to prompt a change to this odd exemption, and the US Copyright Office will be releasing a report studying the issue in the near future. Way to take a stand!

#yourenothelping Award for Archives: Digital Photo Frames

I know all the HGH we’re taking is giving us enormous heads and wide bodies, but imagine those heads stretched from 4:3 to a 16:9 aspect ratio. We don’t have to worry about preserving digital photography because our great-great-grandchildren will be so freaked out by the monstrosities they see that they will destroy them all anyway. The insidious infiltration of devices like these (and widescreen televisions) present a major need area for media education.

Archive of the Year: That Box of Photos Under My Bed

It’s got some really great stuff in it. I swear I’ll get around to taking care of it in 2012.

Happy New Year!

Don’t Kill The Carrier Part 1 — The Digital Dilemma Is A Communication Problem Not A Format Problem

1 December 2011

My first experience with 16mm home projection was during a sleepover at a classmate’s home. I was 7 and at the time in a private school in southern Oregon, which meant my classmate A) either lived in town or in an even smaller town somewhere within a 50 mile radius (it was the latter), and B) that his parents were either overly strict, religious, or anti-authoritarian (it was primarily the latter). For those of you not from the West Coast, this type of anti-authoritarianism tends to manifest on a broad continuum, with the peacelovehippies on one end, the Manson hippies on the other, and bulk represented in the middle by more of a Bakersfield/Five Easy Pieces kind of vibe.

Of course segments of these types mix together in contradictory ways. At my classmate’s house we were forbidden from watching Three’s Company because it was too racy, we went to a natural food store for snacks made from various puffed or toasted grains (after sneaking some Nerds and Bottle Caps on our way from the bus to his home), and we spent the evening watching 16mm educational films because his father worked for a distributor and could get a projector and films for free.

So my associative experience with 16mm film projection? Some combination of awe over moon landings, malnourishment (70s health food was a much different [soy-based] beast than what is available today), and primarily discomfort and slight concerns over my safety in case I made a reference to Loni Anderson or Soap. In my mind, viewing a film film in a non-theatrical venue equates to nervousness, low level fear, and hunger.

What, then, does this mean in terms of the format? Nothing, really. 16mm is not inherently Manson-like (8mm, perhaps), but these are my emotional attachments to the viewing experience. This is nothing against the format or the filmic experience — my next 16mm viewing came 20 some odd years later on a Brooklyn rooftop, discussing the deep magenta tone of a NYPL print of On The Town in between reel changes with my NYU archiving cohorts. There was probably a similar degree of fear and hunger involved, but, overall, a rather different experience than the earlier one.

Between these endpoints, my primary interactions with Cinema were the multiplex, television, home video, and TV/VCR combos rolled into classrooms. My film classes at two universities before NYU utilized projected VHS tapes, either from the library, Blockbuster, or dubbed from TV. Despite my chosen career and the obvious aesthetic qualities of film, my life and the lives of the bulk of people I know have to make me assume that over the past 30 years these types of experiences with movies are more representative of the broader culture than actual film projection.

And it is exactly these points of personal experience and aestheticism where the film-as-film preservation argument runs into the first of many impediments — not due to a question of quality but a question of how we communicate across a broad audience. We can write touching paeans about our personal attachment to film or create masterful homages to certain styles or periods in cinematic history, but in the end we have to consider whether these great enlightenment sermons are converting souls or just creating an emotional buzz for ourselves, whether they push ideas ahead or are more like resigned obituaries looking to reify the past ere it dissipates forever.

We also have to consider that media archiving and preservation extend well beyond motion picture film. Within the past 20-30 years how much content has been created on video as opposed to film? And what of audio? These media types do not have a viable long term format to migrate to outside of the digital realm, and many of them are already born digital. Perhaps we need to ask ourselves if a fundamental rejection of digital preservation and the work needed to establish archival methodologies in favor of film is ultimately detrimental to the preservation needs of non-film materials as well as the presentation needs of existing digital cinema.

The personal narrative can be an effective rhetorical angle, but it is not the entire argument. In order to more successfully advocate for the importance of media archiving and preservation we need to acknowledge that the unreceptive do not typically travel the Damascan road. Within the humanities, critical arguments based on the appreciation of all that is sweetness and light are valid but limited lines of reasoning. Limited because aesthetic arguments tend to be easily dismissed by those not of like mind or similar background as mere opinion or too soft, but also limited because it does not take full advantage of the skills a humanities education provides: analysis, questioning, interpretation, empathy, awareness of audience, historical perspective, and more.

As with all formats, the risks associated with digital media and its material differences from film are real and definable. The way those risks and differences are communicated — both in terms of creating awareness and establishing means of dealing with them — will greatly affect our ability to deal with the challenges and to gather the resources we need to do so.

Next: Don’t Kill the Carrier Part the Second: The Digital Dilemma is a Resource Problem not a Format Problem

— Joshua Ranger