AVPreserve At NYAC 2013

30 May 2013

AVPreserve President Chris Lacinak will be chairing a panel at the upcoming New York Archives Conference to be held June 5th-7th in Brookville, New York. NYAC provides an opportunity for archivists, records managers, and other collection caretakers from across the state to further their education, see what their colleagues are doing, and make the personal connections that are becoming ever more important to collaborate and look for opportunities to combine efforts. We’re pleased to see that this year’s meeting is co-sponsored by the Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York, another in their critical efforts to support archivists and collections in New York City and beyond.

Chris will be the chair for the Archiving Complex Digital Artworks panel with the presenters Ben Fino-Radin (Museum of Modern Art), Danielle Mericle (Cornell University), and Jonathan Minard (Deepspeed Media and Eyebeam Art and Technology Center). It’s hard to believe, but artists have been creating digital and web-based artworks for well over 20 years, and the constant flux in the technologies used to make and display those works has brought a critical need for new methodologies to preserve the art and the ability to access it. Ben, Danielle, and Jonathan are leading thinkers and practitioners in the field and will be discussing the fascinating projects they are involved with. We’re proud to work with them and happy their efforts are getting this exposure. We hope to see a lot of our friends and colleagues from the area in Brookville!

New Software Development Services At AVPreserve

29 May 2013

One of the core concepts behind the work we do is that because the necessary tools for media collection management and preservation have been limited in scope and because the need for such tools is so urgent, it is up to us as a community to develop those tools and support others who do as well, rather than hoping the commercial sector will get around to it any time soon in the manner we require. This has been an important factor of why AVPreserve has looked to open source environments in developing utilities such as DV Analyzer, BWF MetaEdit, AVI MetaEdit, and more.

While most are aware AVPreserve has been a part of developing those desktop utilities, over the past year we have been doing a greater amount of work in the design and development of more complex, web-based systems we are using for the various needs of cataloging, managing and updating metadata, collection analysis, and digital preservation. With the collaboration of our regular development team and the designer Perry Garvin we work on all aspects of frontend and backend development, from needs assessment to wire-frames, implementation, and support. Some of the projects we have been working on are entirely built up from scratch, while others focus on implementation of existing systems or the development of micro-services that integrate with those systems to fill out their abilities for managing collections.

Some of our new systems include:

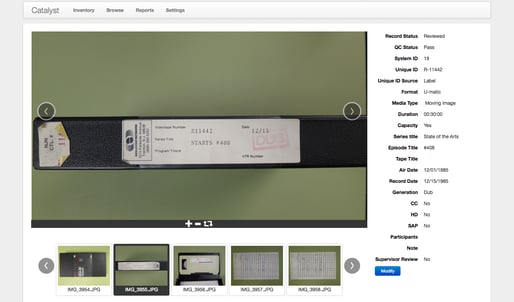

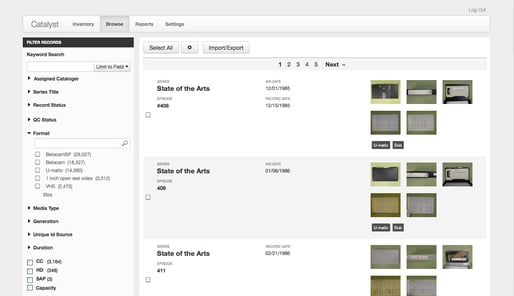

Catalyst Inventory Software:

In support of our Catalyst Assessment and Inventory Services we developed this software to support greater efficiency in the creation of item-level inventories for audiovisual collections. At the core is a system for capturing images of media assets, uploading them to our Catalyst servers, and them completing the inventory record based on those images. Besides setting up a process that limits disruption onsite and moves the majority of work offsite, Catalyst also provides an experience-based minimal set of data points that are reasonably discernable from media objects without playback. This, along with the use of controlled vocabularies and some automated field completion, increases the speed of data entry and provides an organization with a useable inventory much quicker. Additionally, the images provide information that is not necessarily transcribable, that extends into deeper description beyond the scope of an inventory, or that may be meaningful for identification beyond typical means. This may include run down sheets or other paper inserts, symbols and abbreviations, or extrapolation based on format type or arrangement. Search and correct identification can be performed without pulling multiple boxes or multiple tapes, and extra information can be gleaned from the images. Catalyst was recently used to perform an item-level inventory of a collection of over 82,000 items in approximately three months.

AMS Metadata Management Tool

The AMS was built to store and manage a set of 2.5 million records consolidated from over 120 organizations. The system allows administrative level review and analytic reporting on all record sets combined, as well as locally controlled and password protected search, browse, and edit features for the data. This editing feature integrates aspects of Open Refine and Mint to perform complex data analysis quickly and easily in order to complete normalization and cleanup of records or identify gaps. Records are structured to provide description of the content on the same page along with a listing of all instantiations of that content where multiple copies exist, while also providing streaming access to proxies.

Indiana University MediaScore

AVPreserve’s development team supported Indiana University in the design and creation and MediaScore, a new survey tool used to gather inventories of collections. Within MediaScore assets are grouped at the collection or sub-collection level and then broken down by format-type with like characteristics (i.e., acetate-backed 1/4″ audio, polyester-backed 1/4″ audio, etc.), documenting such things as creation date, duration, recording standards, chemical characteristics, and damage or decay. This data is then fed into an algorithm that assigns a prioritization score to the collection based on format and condition risk factors. In this way the University is able gather the hard numbers they need for planning budgets, timelines, and storage needs for digitization their campus-wide collections while also providing a logic for where to start and how to proceed with reformatting a total collection of over 500,000 items that they feel must be addressed within the next 15 years.

**************

These are just a few of the projects we’re working on right now. We’re thrilled to be augmenting our services this way and to be able to provide fuller support to our clients, as well as to continue developing resources that will contribute to the archival field. We’re looking forward to new opportunities collaborate and provide solutions in this way.

AVPreserve Welcomes Alex Duryee

24 May 2013

AVPreserve is pleased to welcome Alex Duryee to our team. Alex is a 2012 MLIS graduate from Rutgers University with a specialization in Digital Libraries and comes to us from Rhizome where he worked on the preservation of net- and disc-based artworks. Experienced in web archiving, data preservation, and the migration of content from optical and magnetic digital storage, Alex is working on a number of digital preservation projects with us. These range from developing new tools and software for support of integrity assurance for digital repositories and audio transfers (extending on our work with BWF MetaEdit and Digital Audio Interstitial Errors, to analysis and normalization of a dataset consisting of 2.5 million records. The work he is doing is a part of our growing focus on developing tools and support for managing metadata and digital files in a preservation environment. We’re excited to add this to our continuing services involving physical collections and excited to have Alex on board!

Does The Creation Of EAD Finding Aids Inhibit Archival Activities?

22 May 2013

One of the primary outcomes of processing is establishing access to collections, traditionally assumed to be enabled by arrangement and description of materials and generation of a finding aid. The theory here is if you can find an item’s exact (Or approximate. Or possible.) location within a shelf or box or folder, you can access it.

If I haven’t explicitly stated it, I hope that some of my other posts have at least inferred that this concept is a fallacy, because the discovery of an audiovisual item does not assure accessibility to its content if that object is not in a playable condition. Access may come eventually through a reformatting effort or researcher request, but that is not a certainty.

This is why I have written that, in most cases, the outcomes of processing audiovisual material needs to focus on planning and preservation activities first. The archivist’s responsibilities include provision of findability, accessibility, and sustainability to collections. Processing has the capability of hitting at least parts of all of these marks, but, given that a focus of processing is generation of a finding aid, those responsibilities can at times be seen through that prism, the every problem looks like a nail thing. The danger here is the potential for the finding aid to become the endpoint rather than a stepping stone to further collection management, especially in institutions dealing with severe backlogs and growing collections.

Of course it can’t be expected that all archival activities support all needed outcomes. However, in spite of the traditional thinking that multiple touches of the object for cataloging or processing lead to an increase in the cost of managing that asset, I feel we have to start looking at the approach of making multiple passes on the object and its content in order to help achieve description, accessibility, and persistence.

If we are looking to optimize the use of resources by focusing on the outcomes they support, we need to ask if those outcomes are being optimally realized. In other words, if we are focused on producing finding aids, are those actually doing the job we think they are.

To put it succinctly, no, not in the way they could and the way they need to be.

I’m talking specifically here about EAD-based finding aids. I will not discuss the structure of that schema here nor the structure of DACS because, though they have not been ideally suited for audiovisual collections in the past, that is not the issue here. Rather, the issue is that EAD finding aids are not doing the job of being findable because EAD is not discoverable through Internet search engines, and the records or online aids themselves are frequently segregated from the library’s catalog or main site.

Even in cases where box and folder browsing is sufficient for onsite access, this lack of integration and external searchability inhibit discovery and use by a wider community. And we’re not really talking anything complex here like linked open data or developing a brand new schema. EAD already has an LOC (and likely other) approved crosswalk to MARC and other standards. With legal exceptions, why wouldn’t all finding aid records also be in the main library catalog? And why are finding aids frequently buried within the Library website under multiple clicks to the Special Collections and Archives (which may even be divided out further if an organization has multiple archive divisions) rather than being front and center along with access to the public catalog?

I understand that there are often extenuating circumstances here, such as collections with access restrictions or sensitive content. However I can’t help but suspect that this segregation is in part self-imposed, coming out of an outdated paranoia about limiting access to “approved” researchers or obscuring the contents of a collection to avoid legal issues. Or, alternatively, self-imposed by the enforcement of traditions and standards that have, for the large part, failed to adapt to changes in culture and technology. Changes which, to be honest, are not new. Motion pictures have been around for over 100 years. We’ll see how well the new DACS addresses audiovisual content, but, even if the issue is slightly better resolved, why has it taken this long?

There is nothing inherently wrong with the concept of finding aids, but there is something wrong with funneling resources into an inefficient system. This was the lesson of MPLP, though Meissner and Greene’s approach was to attack the inefficiency of the methodology. Having reviewed that, we also need to review the outcome of that method similarly and ask if the outcomes are meeting the needs of those we serve — our users, our institutions, and our collections — and if the outcomes support sufficient return on the investment of resources.

We have to admit that we often have a limited opportunity to test that ROI because, in part, the lack of access perpetuated by inadequate means of findability creates a self fulfilling prophecy of lack within archives. At administrative levels, limited resources are allocated to collections because limited access suggests such resources are not necessary. At the ground level, that lack of resources makes caretakers wary of promoting greater access because providing that access is difficult to support by under-staffed departments, and so they do not (or cannot, as is often the case with audiovisual materials). Back at the administrative levels, usage or request reports show that rates are not significantly increasing, proving that resource needs remain minimal because requests and fulfillment of access to records is minimal. And the cycle continues. No one is served. Not the administrator, nor the archival staff, nor those whom they aim to serve.

Frankly speaking, the search portals in libraries and online are probably better and certainly more user friendly than EAD finding aids. I’m not saying we need to jettison finding aids entirely because they contain much information that supports context, provenance, collection management, and other archive-specific or internal data. Rather, what we need to focus on more is how we can shape the creation of finding aids so that the data can be mapped to other portals users are more likely to access in a manner that is simple to achieve, does not lose meaning in the migration, and supports the needs expressed in those other systems. Likely this means that EAD is just one of many forms the data takes, not the ultimate container.

There are of course archival institutions working beyond EAD in innovative areas, but overall we have to accept that findability and access are no longer centralized, and realize that the structure of EAD finding aids and the manners in which they are distributed ignore or actively work against that fact. Only by integrating with other systems and technologies can archives maintain necessary authority over their records, more fully supporting archival services and responsibilities in a changing landscape.

— Joshua Ranger

AVPreserve At PASIG 2013

20 May 2013

AVPreserve President Chris Lacinak and Senior Consultant Kara Van Malssen have been invited to speak at this week’s meeting of the Preservation and Archiving Special Interest Group (PASIG) May 22-24 in Washington DC. PASIG is self-described as an “independent, community-led meeting providing a forum for practitioners, researchers, industry experts and vendors in the field of digital preservation, long-term information retention, and archiving to exchange ideas, identify trends, and forge new connections.” The PASIG meetings are critical to the future of preservation because, though the archival and tech worlds frequently work on parallel tracks concerning the same issues, there is a distinct lack of opportunities for conversation and sharing between them. Over the past few years the group has also taken an increased interest in dealing with the complexities of audiovisual materials.

At the meeting Kara will be a part of the Digital Preservation Bootcamp Panel speaking about Best Practices in Preserving Common Content Types for Media, along with a stellar group of digital preservation experts from Stanford University, Library of Congress, California Digital Library, and more. On Day 2 Chris will be a part of the Audiovisual Media Preservation Deep Dive panel discussing our new Cost of Inaction calculator. This analytical tool compares the money invested in reformatting magnetic media and the resulting extension of the media’s life against the cost of managing that media without making it accessible and, ultimately, losing it to decay or obsolesce within the next 10-15 years. Chris’ co-panelists will be Richard Wright (AudioVisual Trends), Dave Rice (City University of New York), and Mark Leggott (Islandora/University of Prince Edward Island).

As always there are a number of great panels and speakers planned, and we hope you’re able to make it this year or put the meeting on your radar for the next one. Chris and Kara are excited to attend PASIG to contribute and learn from others, so say howdy to them while you’re there.

How Do Archives Measure Up?

17 May 2013

Ask any archivist — or most anyone for that matter — what the importance of historical materials held by archives is and they will likely tell you that it is so large it is immeasurable, assuming that that is true and flattering. True, yes, to a degree, but definitely not flattering. In fact, that is one of the big problems with archives — that their value or impact is not directly measurable. We try to measure, and, despite the strength of the adverbs we use (very, extremely, critically, etc.), the measurement is soft because it lacks numbers.

Numbers. As a strict humanist I find numbers to be as much a faith-based system as any other, but they are what most people most easily grasp onto. Especially where money is involved. And that’s a big problem, because archives are cost centers — they take money and produce little direct revenue in return, even when they attempt to through licensing and other grasps at monetization. So instead we have to look to places where we can create numbers and generate reports to impress or prove that we are spending money wisely. This then boils down to number of patrons/requests, number of items/boxes, linear feet (ugh), and hours or Terabytes of content.

These numbers impress in one way (size matters), but we also have to prove productivity, which, unfortunately, has come to be measured by the number of finding aids produced and the number of linear feet processed within a given time. That helps give a sense that processing grants have been well spent, but, as I have argued before, does little to support preservation planning and creating access for audiovisual collections…Not to mention the fact that measurements such as linear feet give little sense to the number and length of a/v assets.

Not that these numbers don’t matter at all, because they do tell a particular story and different parties look to different measurements as meaningful. However, what they are focused on measuring is Return on Investment (ROI) — money in and money (or product) out. Really, though, what we should be looking at right now with audiovisual collections is COI — the Cost of Inaction.

How much are we losing content-wise and money-wise by not spending money on reformatting and other preservation activities? And is this measurable? Yes, it is. How many U-matics do you have in your collection? In 10-15 years those items and their content will be lost if they are not reformatted, and the money spent to store them and do any processing or management work on them all the years they’ve been sitting there will be a sunk cost. How many DATs do you have? How many VHS tapes? How many lacquer discs? How many 1/4″ audio reels? How many 1/2″ video reels? Those are numbers.

And really, this is the point we’re coming to with magnetic media, of measuring collections in terms of loss rather than in the number of assets and their use if we do not act soon. Those linear or cubic feet may remain (plastic takes a long time to go away), but the content will be irrecoverable, whether due to decay or the overwhelming cost to reformat it. I have to ask then, what is the ROI we’re giving to our culture if we let that happen?

— Joshua Ranger

Materialism, Morality And Media Culture

15 May 2013

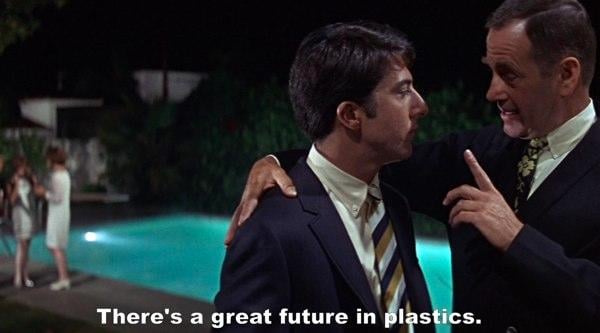

Plastics!

Film buffs know what this means. As in One Word. As in selling out one’s soul to live the life of a corporate middleman. As in a lifetime of creating cheap, soulless, synthetic replicas formed from deadly chemicals.

Film (and other media) buffs also ought to know what this means on a more physical level. As in plastics are a major component of the material object that we love. Plastic helps store the images and signals. Plastic helps transport the movements and sound through the decks and projectors. Plastic encases the hubs and reels, which themselves are often plastic.

Plastics!

So are we sellouts for worshipping plastic and chemicals, despite the warning we received from the past?

Well, apparently not so much, for it seems that digital has replaced plastics as the symbol of mass production and soullessness. In a recent blog post for Good Magazine, Ann Mack explores the analog countertrend to the digital era and decries the intangibility and inauthenticity of the digital as symbols of our fall from grace.

In Mack’s view the imperfection of physical objects makes them more real and more present to our lives than the slick perfection of digital devices. (I would ask if she has ever used a PC or an iPhone in order to review this idea…) The comparison morphs into an battle of real vs. fake. Fake is mp3s and streaming video and emails. Real is a live concert, handwritten letters, and vinyl LPs.

One could easily dismiss the gaps in logic and false equivocations as just part of the nature of blogging (I am not an unguilty party here.), but my sense is that this argument is representative of the general feeling out there around the digital vs. analog issue, as well as representative of how we conflate that issue with an assessment of cultural trends and moral judgement.

When we talk about our love for media there are three possible aspects we are referencing: the materiality and mechanisms of the physical object, the characteristics of the format that present themselves during playback, and the content itself outside of the object/format. One or many of these factors may be an influence on the viewer depending on their level of knowledge and engagement.

For those of us deep in the audiovisual production and preservation field this separation may not seem right. If we love one portion, shouldn’t we love them all for working perfectly in concert to create an experience? Love them all despite their flaws and physical or intellectual failures. And fail media does. Often. Often and often spectacularly.

But the complete formation of this golden triangle is seldom the case. This movie is awful but it was shot and distributed on VHS, so that makes it more interesting…This independent movie overcomes the flaws of how it was produced due to the performances and story…This movie is a minor classic but we’re seeing it projected on a nitrate print so that elevates it…This home movie is amazing but the original was so shrunken that it’s full of gaps and poor image quality…

Really though, these issues are incredibly academic and trend-based in nature. Delving down to that level requires an extreme knowledge and experience with film history that many people would not care about, but it is also linked to shifts in what a cultural moment considers valuable and relevant. This shifts back and forth from the new to the nostalgic, from the analog to the digital — though not all formats are considered equally within their respective categories (audiocassettes have a minor nostalgic following but will never be as respected as vinyl).

I find it interesting that the arguments Mack makes are largely about the experiential — the album cover, feeling paper, face time — and seem to mirror the studio arguments in the 50s on the superiority of the theatre experience over television. In either case this is a facetious argument because the format or experience is not a telling factor of the quality or purpose of the content, but more the individual’s reason or ability to select one experience over the other. A banal handwritten letter is still a banal letter. A film projected on a screen does not necessarily gain in aesthetic or intellectual quality purely due to that occurrence, or the fact that you were eating Goobers while watching it. (But, then again, Goobers.)

But this area of the format wars seems well trod and is not where my interest here lies. To chase a trend in order to explain it seems as frivolous as chasing trends to simply follow them. What I am concerned about is the moral judgement that this analog/digital divide gets saddled with. About the link of authenticity to physical media, to imperfection, and to time away from the screen as Mack puts it.

In and of themselves these are not bad things to be interested in, and neither are their opposites. Where I have a big question is whether we have been tricked into having an argument over the superior format of consumerism and branding. In Mack’s blog the positive examples are about growths in revenue and materialism. Does it really matter if one is purchasing a typewriter or a computer, a DVD or a movie ticket? And what about the moving line of nostalgia? Typewriters are old and cool, but it’s still mechanical and not handwritten. VHS was feared as the death of film, but now, perhaps because the threat was averted, it’s got more cache via nostalgia than DVD or streaming. Do the qualities of a material need to be perceptible to be of value (the grain of film, the touch of paper, the whir of the projector)? These sensual events do have meaning and value, but why is that more important than the intangible, indescribable, or worse, the inconvenient facts of materiality?

In the end, yes, the relative availability of formats or content is market driven, and that has an impact on our ability to preserve materials. But I wonder what happens when we internalize consumption as a point of advocacy or a valuative argument, and then merge that with the moral judgements we make on what and how other people consume. What does that do to our critical faculties, to what we are willing to accept or reject, to latch onto or overlook in our assessment and decision making? And do the results of that force us into a moral rigidity when we need to be much more plastic?

Plastics!

— Joshua Ranger

Chris Lacinak Presenting At ARSC 2013

14 May 2013

AVPreserve President Chris Lacinak will be attending and presenting on a panel at the 2013 Association for Recorded Sound Collections annual conference to be held in Kansas City, Missouri May 15th-18th. Kansas City is one of our favorite American cities, and its deep ties to the history of Jazz and Blues make it especially poignant location this year considering that an overriding theme of the conference will be discussion of the recently released National Recording Preservation Plan.

Chris will be on a panel with Josh Harris from the University of Illinois and Mike Casey and Patrick Feaster from the University of Indiana. The panel ties into the reports’s call to action by looking at three recent large scale census and inventory projects that are forming the basis of institutional preservation plans. Chris will be presenting on our work with the New Jersey Network (NJN) to inventory and provide a roadmap to preserve the 100,000 item program library that was left after the station was shuttered by the New Jersey government. For the project we used our new Catalyst software, a system we developed in-house that uploads multiple images taken of assets by on-site photographers to a centralized server, enabling an off-site cataloging team to create database records from the images remotely. The end result is a database containing both the images and metadata, enabling planning while mitigating the need and cost of accessing the physical materials until selected for reformatting.

Chris is excited as always to be participating in the ARSC conference, and doubly excited to publicly present Catalyst for the first time. We believe our new system can have a lot of impact on the ability to be proactive and more effective in preservation planning, and we look forward to getting feedback on it. Check out the panel and say hi to Chris if you’re not too busy having fun in KC.

Ray Harryhausen Is Cinema To Me

9 May 2013

Ray Harryhausen is cinema to me.

I use the term cinema and associate it with him because my love of the moving image was not forged in theaters but on UHF and early cable television. When I was 5 years old I was semi-disappointed one day when I thought I heard my mom say The Birds was on TV that afternoon, and it ended up being Thunderbirds Are Go. Semi-disappointed because Thunderbirds, Hitchcock, Universal horror, and the cannon of Ray Harryhausen were what captivated me at that time and what made me love the moving image.

I use the term cinema because, as a result of this, I was not tied to film projection as the sine qua non of the enjoyment of watching moving images. To me it is about the creation of illusion, about the frame. It is about the sense that just outside the frame are 30 people, backgrounds that would ruin the historical or geographic setting, and some crazy special effects guy pressing buttons and moving levers. It is about the sense that editing these pieces of film and variations in performance can create an infinite number of works spanning across genres. It is about tromp l’oeil and rear projection and prosthetics and matte painting and animation.

I use the term cinema because, really, for about half the lifespan of film, video and digital moving images have existed. However, though I know they are not easy, on a personal level I dislike CGI and 3-D because they seem easy. I enjoy the challenge and creative thinking that go into practical effects, the skill and mental trickery that give two-dimensional images depth and body.

I use the term cinema even though it sounds tiresome to say that cinema is illusion. But it is not an illusion in magical terms. It is illusion created from skill, imagination, coincidence, and the risk of gut feelings. The illusions often fail from the get-go, or they fail several years later when superseded by other technologies that appear more “real”.

I use the term cinema because it transcends time periods and formats. And though Ray Harryhausen’s techniques were superseded by newer technologies and newer approaches of storytelling, what he did was beyond that. What he did was the Homer and the Shakespeare and the Dickens of moving image. What he did was create a language that was so vernacular and specialized, so common and so unique that it seemed as if it had always existed. That it was an instant classic. That is was immediately something that any subsequent filmmaker had to copy, adapt, or work against.

I use the term cinema because it is the only high-falutin’ term we have for this type of thing, and because Ray Harryhausen has passed away, and because I wonder if I would be doing the work I do without the impact of the work he did. Work that enthralled me. Work that inspired me. Work that educated me and made me seek more. Wort that made me pretend to be sick so I could stay home from school and watch Jason and the Argonauts on the Bowling for Dollars Afternoon Movie.

Thank you, Ray.

— Joshua Ranger

More Podcast Less Process

5 May 2013

A 10-episode podcast series produced by AVP and METRO (www.metro.org) and funded in part by the New York State Archives Documentary Heritage Program.

More Podcast Less Process features interviews with archivists, librarians, preservationists, technologists, and information professionals about interesting work and projects within and involving archives, special collections, and cultural heritage. Topics include appraisal and acquisition, arrangement and description, reference, outreach and education, collection management, physical and digital preservation, and infrastructure and technology.