Community-centered design for the development of effective cultural heritage training programs

January 27, 2023

by Pamela Vizner and Kara Van Malssen

Continuing education and career-long professional development is critical in any field. As professionals dedicated to the stewardship and impactful accessibility of content—archiving, digital preservation, and digital asset management—we know well how important it is to continue to grow and learn as technologies change, user and stakeholder expectations evolve, and as we individually advance in our careers.

Both of us have also been privileged to share our knowledge with others around the world. Over the years, we have participated in dozens of local and international training programs as curriculum designers, trainers, organizers, mentors, and supporters; both as individuals and also as part of AVP’s ongoing efforts to support continuing education in formal and informal settings. These programs have been organized by a variety of professional associations, higher education institutions, and international training organizations. In the past, these were primarily in person—a few days or a week of learning with a handful of practitioners, either from the local area where the training was being conducted, or mixed groups from very different regions of the world. More recently, COVID-related restrictions have forced organizations to restructure training programs to accommodate fully remote or hybrid options, and we have participated in these efforts as well.

Throughout the years we have seen, applied, and analyzed multiple educational and training methodologies. We have seen many successes and have also identified areas of improvement, in other programs and also in our own training practices.

Recently, we have reflected on shortcomings and opportunities to deliver more value to the participants of these trainings. This was in part motivated by our 2021 engagement with the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) to help conduct a study on professional development needs for Sustaining Digital Heritage, with the aim of developing a new programme for this topic. Project researchers interviewed over thirty, primarily mid-career, heritage professionals from around the world, and analyzed existing professional development offerings on this topic. The results, and a proposed model for the programme, were published in a report available here. Through this research, we observed that:

- Interviewees were frustrated by the lack of training opportunities for mid- and advanced-career professionals. Most trainings focus on introductory content.

- Perhaps because they are introductory, many trainings largely focus on sharing the expertise of the trainers, which doesn’t always connect to or translate to the participants’ context, background, resources, needs, and goals.

- Remote trainings largely repurpose the onsite model—bringing people together for a few consecutive days of shared learning with experts brought into present live—but without the critical networking component.

- In many training settings, there is a lack of opportunity for trainees to practice applying what they are learning to their own context and push solutions forward.

As the professional development landscape adapts to the new realities and opportunities introduced during the pandemic, now seems like a fortuitous time for the professional communities we work with to find ways to innovate and improve the value of professional development offerings, particularly for the international community. Significant investment goes into the development and delivery of all professional development—designing and optimizing for impact is a shared goal by all stakeholders.

In this reflection, we want to offer some thoughts and ideas that we think could improve these training offerings to precisely maximize their impact while taking advantage of the new technologies and sharing opportunities available to us.

Our recommendations are rooted in human-centered design, a problem solving method that focuses on understanding and empathizing with people in order to develop beneficial solutions. It is worth noting that our recommendations here focus only on professional training programs that are not part of formal educational opportunities offered through universities or similar institutions (e.g. undergraduate programs, master programs, or certificate programs).

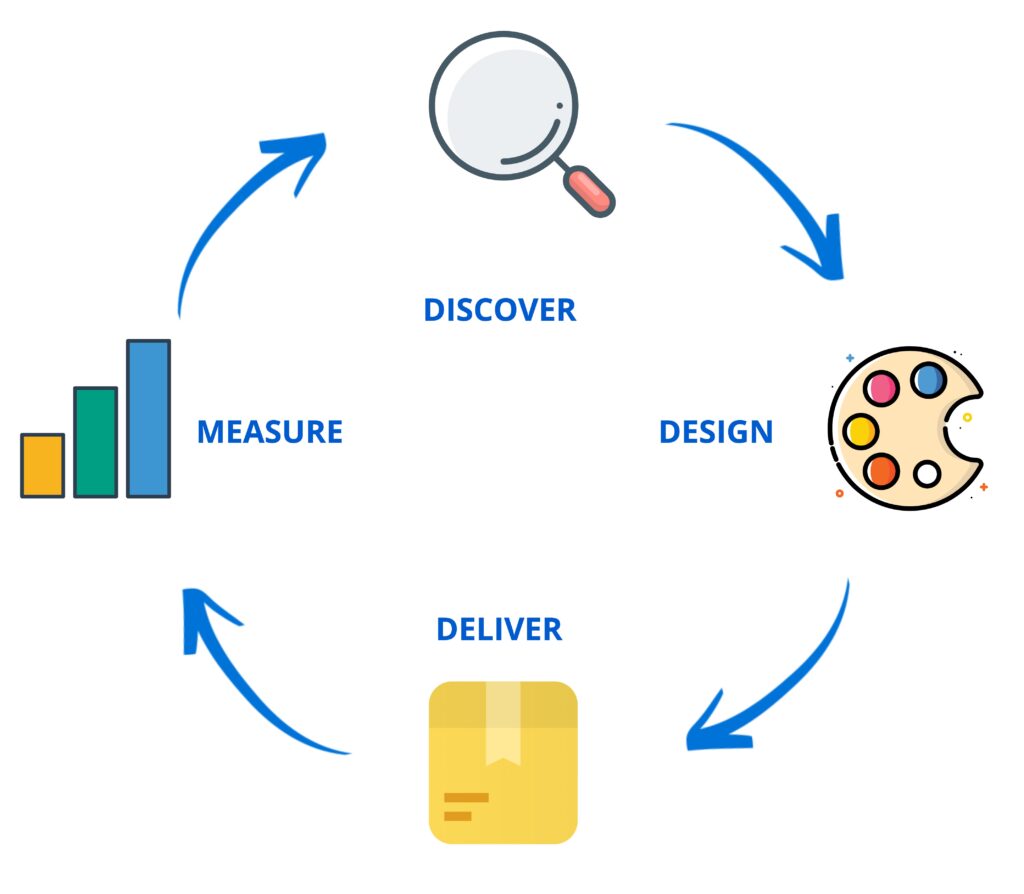

The key question we want to explore is: How can we ensure the resources invested in professional development offerings—on the part of organizers, trainers, participants, and funders—delivers the most impact? Our recommendation on how to achieve this can be summarized as:

- Discover – Take time to understand participants contexts, background, resources, needs, and goals first

- Design – Design training programs that provide ample opportunity to blend theory and practice.

- Deliver – Take advantage of the different opportunities afforded by asynchronous and synchronous learning to maximize shared time. When possible, reuse existing content.

- Measure – Take the time to evaluate the results of the program, build in this practice for every iteration of the program to gather feedback to use as a tool to improve it.

DISCOVER

In our role as consultants at AVP, our approach with clients focuses on identifying the problem before proposing any solutions: we ask, we listen, we analyze, we engage in dialogue. Then, we find answers together. In other words, we diagnose before we prescribe. We have found this is the only way to find realistic solutions for a problem as each context is unique.

One area of concern that we have identified is the lack of understanding of local contexts in the design and implementation of professional development programs. A common assumption seems to be that one single solution can be applied in multiple contexts with success.

We have seen many programs lack a clear “discovery” process. In the context of international education, this means that curriculum designers do not take the time to get to know their audience. Moreover, trainers often come from regions where availability of resources is different and where the problems they are trying to solve are of a different nature. As a result of this, programs can not only be ineffective but also run the risk of being perceived as colonizing. These exact solutions will very likely not translate well in a different context. Furthermore, many training programs in our field emphasize technical skills, and in some cases we have seen that the most pressing needs for a community might not even be of a technical nature. Very few programs include topics such as project management or fundraising, for example, which are fundamental in archives management.

Taking the time to understand trainees’ needs and pain points is key for the design of an impactful program. This can be done through surveys, interviews, or site visits, if possible.

DESIGN

When there isn’t an understanding of the participants’ needs, the design of a program is destined to be built without a foundation. The selection of content, topics, tools, and training methods are left to the assumptions of the organizers, who might have a limited understanding of the needs of the audience they are trying to reach and without a clear set of articulated goals they want to achieve.

The first problem we see is that this often leads to the design of programs that are mostly expository and do not include opportunities for facilitated dialogue, which in many cases helps with absorption and retention. We are not saying that lectures and presentations don’t have any value but not including facilitated dialogue can leave participants without a firm understanding of how to translate what they are learning to their context.

In addition to this, trainers are often subject matter experts, in some cases renowned professionals with many years of experience, but they are not trained to be facilitators to engage in active problem-solving with participants. Often, there’s no space for collective problem-solving. This one-sided modality has gotten more and more popular with remote options as sometimes it is very difficult to moderate discussions online with large groups. Again, that is not to say there aren’t benefits to applying remote learning, but we are sure at this point we have all experienced the challenges of open communication within remote platforms in educational contexts!

Moreover, because no discovery has been conducted, when hands-on training is included the tools that are presented are very specific and not necessarily can be applied in every single situation. This means that by the end of the program attendees are left with a large set of tools to apply without really knowing how to use them or if they even apply to their own context. For example, open source tools are often presented as the right solution for under-resourced organizations, however, in the selection of a tool there are many more aspects to consider than just availability of financial resources (and open source does not equal free, a point often under communicated).

We believe that in order for current programs to be effective and have a long-term impact a major perspective switch is required: developing curriculums with a problem-solving approach and trainee-centered learning. We think that learning the theory alone does not provide the tools to equip archivists and technicians to find the right solutions for the problems they face, which can vary greatly from organization to organization. Each organization is a different world and their problems and possible solutions are unique. After doing a good discovery, the design of a trainee-centered program not only makes a lot of sense, it also comes together more clearly.

A trainee-centered approach to teaching and learning may inspire different program designs than the typical default approaches.

DELIVER

We believe in taking advantage of the technologies and resources we have at our disposal. Program designers can be creative as long as they keep in mind the goals and needs identified during their discovery and while maintaining a trainee-centered approach. A combination of synchronous and asynchronous learning could be a good solution to maximize time and resources while keeping the program effective and successful. Asynchronous sessions could be followed by group working sessions—in-person or online—where participants have the opportunity to ask questions, apply the newly-acquired knowledge in practical exercises, and discuss the topics presented in the asynchronous sessions. They can learn from each other, and come up with creative solutions together. Allowing participants to review concepts ahead of time would not only provide space for reflection and reinforcement, but also maximize the time participants and trainers spend together.

In this context, the role of the trainer, rather than being a lecturer, switches to a facilitator who guides participants through their own process of discovery as they try to marry theory with their own challenges. This implies that the trainers’ skills are different: this person should be a subject matter expert but also someone who is capable of guiding a conversation, challenging participants, and facilitating team work. This also means that the trainer needs to spend some time learning about the participants’ needs so they can offer effective guidance and help them find the right solutions. They need to do their own “discovery” process, know how to listen, be open, come in without preconceived notions of what the participant’s context is about, what they know and what they don’t, what their roles are within their organization, and what their expectations might be. On the other hand, participants should come prepared to share examples of current challenges for discussion and engage in collaborative problem-solving. Clear guidelines on expectations of participants and how to come prepared would be helpful in aligning all parties for productive time together.

Another advantage of this two-phased approach is that evergreen content can be created ahead of time. This can be reused, shared, translated, etc. If during discovery you have identified needs in broader areas, such as project management, then there’s an opportunity to reuse content from other sources. Obviously, there are many programs and content out there that can be used in tandem with domain-specific content. Partnerships with other educating organizations could cover the basics of general topics to facilitate access to already-existing content.

MEASURE

Determining the impact of the program must go beyond simply a feedback form delivered immediately after a training session. Instead, during the design stage, articulate a goal (or goals) of what you want the training to achieve, then determine what key performance indicators would be useful to measure to understand if you have achieved those goals. Next, determine how this information would be gathered.

For example, maybe one of your goals is to increase collaboration amongst participants in a regional training event. In order to determine if this goal has been met, you may want to track engagement on certain platforms, or whether or not they have organized follow up events. If one of your goals is for participants to be able to test a certain tool for their workflow, you may need to send participants home with clear instructions for testing. Later, follow up to with questions asking whether they completed the test, how easy was it to complete the test, how likely they are to adopt the tool.

We believe the end of the training cycle is not when the last session is over. Learning from past experiences is invaluable and will help build a better, more sustainable, more effective program. Asking participants, trainers, and other parties involved what they think, at the right moments, will give you information to continue to improve and better allocate resources in the future. Besides feedback forms, finding other ways to measure impact can be beneficial in planning future sessions. You can also design evaluation tools that are reusable so you can use this historical information to measure progress over time.

APEX: A CASE STUDY

The Audiovisual Preservation Exchange (APEX) is an international program that encourages dialogue and non-hierarchical exchange between practitioners, students, and the general public around the management and use of audiovisual collections (physical and digital). Organized by the Moving Image Archiving and Preservation Program (MIAP) at New York University (NYU) and created by Mona Jimenez, APEX has collaborated for the past 14 years with different types of organizations—including national archives, libraries, documentation centers, and community archives—to foster dialogue and mutual learning through direct work with collections. APEX is organized once a year in a different location, and previous versions have been held in Ghana, Argentina, Colombia, Uruguay, Chile, Spain, Brazil, Puerto Rico, and Mexico. AVP has been a long-time collaborator of APEX since its creation in 2008 through the participation of staff members in a variety of activities —including training— and as a current program sponsor.

APEX is not a traditional training program—everyone is a contributor and participants all learn from each other’s experiences navigating and responding to diverse administrative infrastructures and availability of resources. Its open-ended methodology embodies the approach we have described here, in a flexible and collaborative way.

APEX starts with dialog (akin to the discovery stage described above), followed by a collaborative design process between partners. Then content delivered is based on identified needs and according to the resources available. Outcomes are measured and the process iterated on each year.

Different from many international archival programs, APEX has a community-centered approach: each year, APEX organizers and local partners define the specific activities based on the communities’ needs. In some cases, most of the effort is focused on working on specific collections to find solutions to specific problems. In some other cases, the program includes hands-on workshops with the broader community to raise awareness around care and management of their own collections. To make this possible, APEX organizers work hand-in-hand with local partners to design the most impactful program possible.

Over the years, we have learned that the discovery process is key to a successful program and we have incorporated that as a fundamental part of the initial planning. This process starts with meetings with partners, followed by surveys, and in some cases site visits which are incredibly helpful to understand contextual information that might not be mentioned in conversations or surveys. Having the opportunity to see the spaces available, the collections, and the equipment; understanding any cultural differences or barriers; and having the opportunity to engage in person with partners has been useful information to prepare a program that is achievable, makes sense for all the people involved, and that focuses on the right topics.

The design of the program is a long, collaborative process that can take several months. Based on the information gathered, activities are proposed to partners. These are discussed, refined, then discussed again. Every attempt is made to maximize the resources available (equipment, lodging, transportation, working spaces, technologies, existing documentation, etc.) and use collective networks to find additional resources and required skills to align with the needs identified (e.g. equipment donations, reaching out to a colleague who can collaborate with information on a certain topic, etc.).

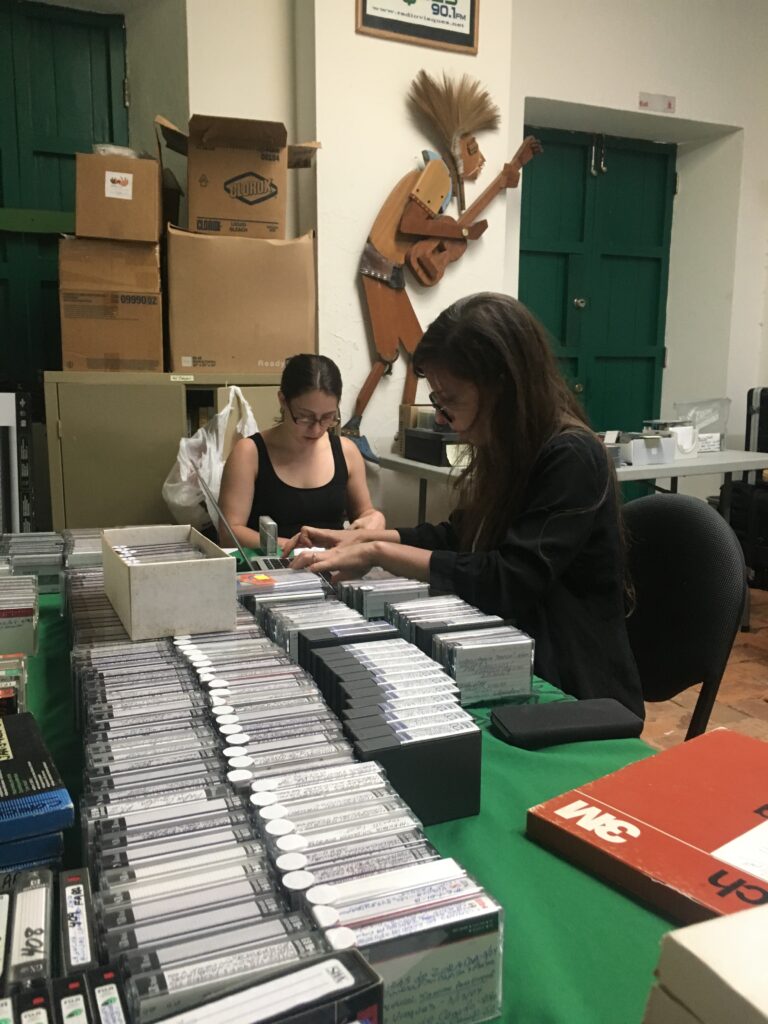

Delivery always varies. APEX is an in-person program, although in 2021 we were forced to organize a virtual version. In some cases we can organize online sessions with a colleague over video call to explain or discuss a given topic. There is only one thing that remains the same for each version: we ALWAYS engage in dialogue and learn from each other. The hands-on work with collections is the catalyst to discuss broader topics: as we work together to inventory video tapes we discuss approaches to digitization, and inevitably questions about digital preservation come up. Local organizations learn from each other as they uncover ways to collaborate or to learn about local resources they didn’t know existed. Every single version of APEX is not just a learning experience, it is a human experience that strengthens our networks at every level, from professional to personal, from local to international. This impact enables the creation of long-lasting connections and collaborations that live well beyond the duration of the program.

Finally, measurement of success is often done internally. Every single version of the program has resulted in learnings that are incorporated into the planning of the next version. However, there is still some work to be done in this area. APEX has recently created an advisory board that hopefully help formalize processes even more, and open it up to broader communities who can take advantage of this model in other locations.