Explore

Thanks For The Memories

23 November 2009

Like the person who always wants to order last at a restaurant because they haven’t made up their mind yet, I always get stuck at the dinner table on Thanksgiving trying to think up something that’s the right blend of witty and sweet for the “I’m thankful for…” round robin. It never quite comes out right (but then again, neither does the turkey), so I thought I might give it a little forethought this year by considering what I’m thankful for this past year in the archiving & preservation world.

I had a few thoughts running through my mind on this one (which I suppose is a virtual tidal wave of action compared to normal). I could go culturally significant and choose something like The Red Shoes restoration or the discovery of missing footage from Metropolis. Or I could go nostalgic route and choose the release of Nirvana Live at Reading (can you guess my age?). Or I could go the mind-blowingly amazing route: There have been some advancement on the Leon-Scott front, but nothing will beat experiencing the premiere of the earliest known sound recordings at the ARSC conference in 2008.

But, no, it’s Thanksgiving; the sentimental always wins out on holidays. So I’ll have to go with the transfers my wife and I had made of some of her dad’s family’s 8mm home movies through the Standby Program here in New York. I’m thankful there are still companies doing quality work in this area, and I’m thankful for having the ability to make these films and memories accessible again. I don’t think the family had even watched the films when they were first developed, but they watched the transfers over and over and over again when we gave them to her dad. To be able to see old friends, old family members who have passed, and to share the stories behind the images was a special moment.

More special than seeing Kurt Cobain wheeled out on stage in a hospital gown? We’ll have to let history decide that one, but at least now the home movies corner has more of a fighting chance.

— Joshua Ranger

Everything, Everywhere

18 November 2009

“Do we really need to save everything from everybody?”

In the first part of November 12th’s episode of Soundcheck broadcast on WNYC in New York (“Vintage Soul Gets a Second Wind”), host John Schaefer spoke with Ben Greenman of The New Yorker and soul singer/producer Syl Johnson about the current (micro) trend in reissuing obscure soul-music albums from the 1950s-70s. Many of these mildly popular, regionally popular, or not at all popular performers have begun to tour again or play one-off shows nationally and internationally based on the new found interest in their work.

As discussed in the segment from the show below , and as I have personally witnessed at some concerts in Brooklyn, these reissues and concerts are most popular among a younger, primarily white crowd. The concerts might be at a predominantly African-American supper club, or maybe at a venue where The Mountain Goats sold out the night before. Whichever the case, it’s the same crowd trekking around the city to check out the latest soul revival, a group of 20 and 30 somethings grooving to the live beat of 60 or 70 somethings who haven’t performed in perhaps 30 years.

Just like the music itself, the interested people are regionally isolated and esoteric. Schaefer and Greenman put forth that this seems to be the province mostly of the audiophile or the culturally astute youth who is looking for more and more obscure things to satisfy that need for something “new.” More generously, Syl Johnson posits that the desire comes from a curious mind seeking further education. This esoteric soul music has been widely used for samples and riffs and inspiration in more contemporary or more popular music. Johnson feels that modern listeners are going back to discover the original source of the bass line or vocal sample in a rap song because they want to better know the history or culture of the music.

As critics, Schaefer and Greenman worry over this issue because their work is concerned with analysis, cultural distinction, and trying to balance their assessment of what is considered a quality work now versus what will be considered a quality work for generations to come. This side of their work has to stand outside of fads, momentary revivals, and the purely emotional. As a musician, Johnson un-worries the issue because, hey, people are listening to the music, and that’s great. His work is being acknowledged and valued again (or finally).

What unites the two streams, however, is the love of the music. Schaefer begins to question whether we really should save everything, but steps back quickly because, even if it’s no James Brown, it’s still good music. As a critic there might be a distinction there, but as a music lover the emotional attachment can take hold. What also unties the two streams is the Archive. It is the preserved work in an archive that enables the access, the rediscovery, the education, and the reconnection with the past. We strive toward the ideal of saving everything because we want to provide that kind of access to whomever, whenever.

As archivists, what we might take from this is that our link in the cultural chain can often be overlooked. As in the case of the soul revival, the discussion of such cultural events are often framed in terms of the end result, accessible production: the documentary that uses archival footage, the digitally remastered CD, the restored print of The Godfather screening at Film Forum.

The press around these kinds of releases tends to focus on the original creators or new producer/distributor, not the source for the production. The re-issue of an album, or the release of a DVD, or the creation of a YouTube video are not the preservation of the material, they are result of archiving and preservation work and should not be confused with those efforts. As this review of the Eccentric Soul Review in the Times describes it, the record labels “[delve] into obscure archives for meticulously researched reissues.” The archives are there, holding the material that is then being exploited by others.

Access is good. Access is the goal. Reissues and such perhaps bring more awareness and financial support to the source collection, but access and use of materials is the benefit of preservation, and that effort should be recognized as integral to the cultural productions that feeds from our work.

— Joshua Ranger

Winds Of Change

13 November 2009

I caught this Tweet from Archive Alive about a new collaborative website for collecting media related to the Berlin Wall (www.wir-waren-so-frei.de). November 9th was the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Wall, a memory marker I wasn’t aware was happening until suddenly being inundated with news stories the other day. The site itself is in German, but that doesn’t take away from the great use of images, video, mapping software, and other kinds of web-based functionality that organize, track, and give a fuller sense of the history around the Berlin Wall and Germany at the time. The topic (and the forgotten significance of this date) really got me thinking about what a seminal event that was for millions of people at the time, but also how it’s really a touchstone event for my own feelings about history, memory, and the importance of archives.

It’s difficult to recall now, but growing up at the tail end of the Cold War was kind of a fearful time. I did not hate the Soviets or communists — they were just people, living their lives like everyone else — but I knew plenty of people who did, and there was a constant dread hanging in the air that some leader on either side could just lose it at any minute and utterly destroy the whole world. Maybe it was because I was young, and maybe children today feel that same way, but I have a very specific memory-feeling associated with that period that I don’t have now.

Staying out of any ideological argument over the superior politico-economic system or any kind of post-facto Ostalgie, it seems difficult to argue that the Berlin Wall was a good thing. Denying freedom of movement, communication, and open access cannot be good for a society.

I saw the ecstatic reactions on the news in Berlin and the Eastern Bloc as these shackles were left to fall open, but the magnitude of the reaction was really brought home while I was far away from home, living in Pardubice, Czech Republic in 1997-98. I listened to stories from my landlords who had lived under both Nazi occupation and Communism about the ways they learned to survive; from friends who had had educations and careers derailed because of petty party politics; from the people who looked at my passport with wonder not necessarily because they loved America, but because it represented the ability to move and live freely in the world; and finally from the people who just wanted a chance to share their story with someone. The depth of the stories and emotions really opened my provincial Oregon eyes.

What shocked me equally was the richness of eastern European history – even of recent vintage – that I had not been taught while growing up, simply because we did not deign to study the enemy. Some shackles are much less noticeable, I suppose.

So here we are now, at this anniversary of great world and personal import: Possibilities opened up to millions, a decrease in fear and turmoil, and possibilities & knowledge opened up even to we who thought we already had them all. And yet, it took a Twitter post on some online images for me to even remember any of this. The memories are there, filed away, but the context and the lines of access fade.

This makes me consider my siblings and their generation. Not much younger than I am, but just enough that it seems they have no concept of these historical events that have caused such strong feelings in me. To them it may just be the last 10 pages of a history book, some funny hairdos and clothes, or some bad pop music.

How do we maintain the intangible? The unreliable? The question then becomes not just one of the persistence of an object, but also of the associated stories and memories, the unwritten annotations that provide added context and interpretation.

But perhaps what feels like grasping at fluttering memories is not so problematic as it seems. Perhaps there is a lesson here on the symbiotic relationship between image/sound and memory. One may fret about the fading of memories, but the visual and aural prompts created by media reach deep into the brain like the way that tastes and smells do. This is not only why we need to preserve audiovisual materials, but also why we need to have ways to access and use them. It’s how wir werden frei bleiben (we will remain free).

—Joshua Ranger

Enhancements Are “Sexy” – Efficiencies Are Mundane

1 November 2009

While an underlying premise of OTR is that the resources freed by efficiencies can be redirected towards enhancements, it is tempting—as our group has done—to recommend many more enhancements than efficiencies. Enhancements are “sexy;” efficiencies are mundane.

Your Archive Deserves Advocacy! (YADA!)

21 October 2009

YOUR ARCHIVE DESERVES ADVOCACY ! (YADA!)

In support of UNESCO World Day for Audiovisual Heritage (October 27, 2009) and American Archives Month, and in celebration of the work being performed by archivists worldwide, AudioVisual Preservation Solutions (AVPS)requests your participation in a project designed to garner support for audiovisual archive preservation planning and project implementation from influencers, policy makers and funding organs.

As consultants and advocates working with audiovisual archives, we contribute to and witness preservation success stories on a daily basis. We understand that those successes were built on sustained long term efforts and collaboration with other internal/external stakeholders, and through community information exchange. Our celebration of these successes can lead to the kind of funding support all archives need in reaching their goals. We are asking you for your favorite audiovisual preservation experience at your archive. These stories will provide encouragement to other archivists by showing what can be achieved in similar circumstances.

These stories will be published on our website, and some will be selected for use in our ongoing efforts to inform private and public funding decision makers, both of what is being achieved, and what can be achieved with their support.

Our first inclusion is dedicated in support of the spirit underlying UNESCO World Day for Audiovisual Heritage and American Archives Month, and will profile the ongoing story of “The Jazz Loft Project”, www.jazzloftproject.org/index.php an excellent example of how a person or organization convinced of the cultural value of previously inaccessible audiovisual content was able to garner the support necessary to both make unique materials accessible, and to preserve them for posterity.

Because all archives deserve advocacy, your story deserves to be told.

Please contact AudioVisual Preservation Solutions at www.avpreserve.com/you , or send us an e-mail at [email protected] , or call us at 347-241-2920 to leave contact information. We will follow up with guidance on telling your story. Please Support the preservation projects of the archive community overall by getting your story told.

We will provide periodic updates on subsequent phases of this project as it progresses, and a blog will be posted on our website on Wednesday, October 27th in celebration of UNESCO World day for Audiovisual Heritage.

Thank you for your participation, and we wish you success on all of your preservation projects.

Access Qualities

16 October 2009

The Library of Congress has recently posted a number of silent animations to their YouTube channel. I like how you can “see the strings” so to speak (how the animation was done) on this film based on a comic strip by Pop Mormand… but it was cute, too:

This isn’t a dis on the LOC (you have to work with the source material you get, and these are just access copies), but the quality of the sources and resulting transfers and then compressions to a YouTube level format is variable. There’s flickering, light issues, and just some overall poor image quality. Plus I sat and watched them on my laptop while drinking my morning coffe. All in all it wasn’t exactly the pristine cinematic experience.

But there’s a part of me that says that’s all right. I grew up in small Oregon logging town. There was one library within a 60 mile radius, and if it was closed you were out of luck for doing research. There were a few movie theatres (and even a drive-in!), but the edgiest fare we got was something like a double feature of Big Top PeeWee and Short Circuit 2. And that was the county capitol, so there were people who had even less access to these things.

And access is what it comes down to. One of the things that drove me into the field of archiving and preservation was this strong feeling that all people deserve equal access to information, culture, and education. Impossible? Maybe. Can I do something to increase access just a little bit more? Yes. Maintaining preservation standards and striving for archival ideals are important, but creating access to materials is the parallel mission.

I didn’t experience these animations to their fullest, but now I know they exist and I have the desire to see better versions of them, let other people know they exist, and support their further preservation. I also learned a little something about film history and animation. And, ultimately, they made me smile and laugh. Even at this remove from the originals, they brought a little joy to my morning, and I’m grateful to the Library of Congress for making them available.

— Joshua Ranger

Masstransiscope

8 October 2009

A follow up about tonight’s talk by Bill Brand at the Transit Museum in Brooklyn on his public art project Masstransiscope. Installed in 1980 in an abandoned subway station and restored in 2008, Masstransiscope basically creates a life-sized zoetrope through the interaction of the moving train and the positioning of the images, lights, and view holes.

This is a magical work of art that surprises and delights me every time I view it on the train, right up there with walking across the Brooklyn Bridge and seeing the Statue of Liberty from the Staten Island Ferry.

Bill Brand is a filmmaker, film preservationist through his company BB Optics, and a teacher of filmmaking and preservation. I caught his talk on this back in June. Entertaining and informative about the mechanics of moving image devices like zoetropes, about his process for creating the work, and about the recent preservation process. Highly recommended to check this out or some of Bill’s other work.

—Joshua Ranger

Andy Lanset Of WNYC Honored By NYART

7 October 2009

We tweeted about it last week, but it would be remiss of us to not more fully congratulate Andy Lanset of WNYC Archives for being honored with the Award For Archival Achievement by New York Archivists Roundtable. (Kudos also to the winners of the other awards, Columbia Center for New Media Teaching & Learning and Westchester County Executive Andrew Spano.)

Andy has worked tirelessly to centralize, organize, preserve and make accessible over 80 years worth of broadcast materials in all manner of formats. His efforts have reformatted and digitized a collection that spans almost the entire history of radio and that has become a valuable living resource for WYNC and other users. WNYC listeners (and listeners of stations which broadcast WNYC programs) are reminded of Andy’s contributions and the significance of WNYC’s audio archives on a regular basis. Almost no day goes by where Andy Lanset isn’t thanked and credited on air for making the amazing content held in the WNYC archives accessible for incorporation into current programs.

Andy got his start as a volunteer and then staff reporter at WBAI radio, and in the mid-80s he began freelancing with NPR as well. His work as reporter and story producer led to a greater and greater interest in field recordings and the use of archival materials in documentary pieces. This led to an increasing focus on recording, collecting and preservation work. Through his own initiative and continued pestering regarding the great importance of their collection, Andy essentially created an Archives Department and Archivist position at WNYC in 2000, which quickly grew and has become a model archive. He continues to work closely with the NYC Municipal Archives and their WNYC holdings which make up a significant portion of the older WNYC collection.

Andy’s well deserved honor reminds us of the multi-faceted aspects of being an archivist. It’s easy to get caught up in or bogged down by the technical ins-and-outs of archiving: storage, handling, arrangement, metadata (oh my!)… However, caring for a collection also benefits from a passionate advocacy for its contents. How we express our love for the content and the media. The stories we tell about the work we do. The ability to place materials in a historical and/or artistic context that all levels of users can understand. Getting across just a little bit of the enthusiasm and joy we feel about our collections and their importance can be a powerful tool for increasing support, funding, and access.

We’re not saving the world, but we’re preserving a little piece of it. Let’s hear it for Andy for doing his part to keep the tape rolling.

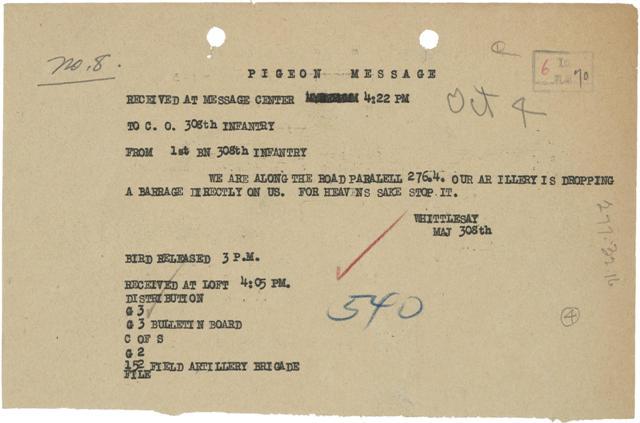

Pigeon Message

5 October 2009

From NARA’s Historical Document of the Day, transcription of a note sent via messenger pigeon during World War I — The same kind of “media format” referenced in one of our banner images. I guess they had to do an “open with” and “save as” on a typewriter in order to access the attachment.

America’s Next Top Presidential Libraries Model

4 October 2009

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) recently published their Report On Alternative Models For Presidential Libraries, an institutional review mandated by Congress to develop prospective archive models that would attempt to balance issues of cost savings, improved preservation, and increased access. (Even the big dogs have to deal with the impossible seeming task of producing more while spending less…)

Though not a light read, it does, like many of NARA’s initiatives and reports, offer plenty of tips, inspirations, or supportive arguments for preservation practices and projects. For example, the importance of “non-textual funding” for creating preservation copies of AV materials is underscored. These assets need a different kind of attention than textual materials, and consideration and funding of that “has resulted not only in better access to holdings, but also improved preservation of the original tapes” (pg. 20).

Also of note in the NARA report are sections like the one delineating proposed changes to how presidential records are processed (pgs. 25-26). Combined with the necessary review for sensitive content and the huge amount of materials suddenly available after the end of a presidency, the heavy influx of requests through the Freedom of Information Act created a sluggish response time. Searching through unprocessed folders while trying to maintain provenance and performing traditional start-to-finish processing became a hindrance to acceptable response times.

Instead, as in other archives, the implementation of a tiered system of processing prioritization has been established which takes into consideration content types. Categories such as “frequently requested,” “historically significant,” or “non-sensitive” are prioritized accordingly, thereby contributing to improved resource allocation and speedier progress.

The five alternative models to NARA’s current operational model are too specific to their history, organizational structure, and mission to discuss in depth here. Instead, three additional important points can be gleaned from NARA’s reporting process:

1. As we know too well, the continual spectre of too much work and too few resources is daunting. Strategic partnerships, pooling of resources, or repository models; exploring new areas to use assets or create access; and exploiting powerful new tools and technologies are just some of the things that should be considered in working to improve the functionality of archives and ensuring their long-term sustainability.

2. The consideration of different aspects of centralization versus decentralization is key. Just as certain audiovisual formats require a reconceptualization of the asset that separates the consideration of content from the consideration of the physical carrier, the archive itself can undergo renewed consideration from the idea of a central location to one of multiple / virtual entities. Of course, this must be accomplished while still adhering to fundamental principles of preservation. What this means is that the “virtual” needs to be understood on its own terms in order to be fully and properly utilized, just as some of the unique aspects of audiovisual archiving have needed to be understood separately from traditional paper archiving in order to apply the same kinds of standards and principles.

3. A finer point is held within Alternative Model 4 (pgs. 43-46) of a centralized archival depository where all presidential records would be maintained, unlike the current model where an archive and a museum are dedicated to a single president and those facilities are located, typically, in the president’s home state. This alternative model would involve building a new facility as well as planning and implementing a large scale digital archive for storage and access — certainly daunting, costly tasks. However, what is of note with Alternative Model 4 is that it has the largest initial cost outlay to implement but that, in the long run, it will provide more archiving jobs as costs can be reallocated from what would have been decentralized facilities, will make for more efficient access, and, ultimately, it will save more money than the alternative models offered that are less expensive at the initial implementation.

Alternative Model 4 has its pros and cons like the others, but an important lesson here is one of time. Archiving and preservation are long range efforts concerning the persistence of the past well into the future. As such, they deserve far-sighted planning and goals. This can be a difficult struggle to implement, and may not have results one sees in ones lifetime, but there are ways to model, to plan, and to advocate for the collection and for the generations to come.

— Joshua Ranger