Select

AVPreserve At PASIG 2013

20 May 2013

AVPreserve President Chris Lacinak and Senior Consultant Kara Van Malssen have been invited to speak at this week’s meeting of the Preservation and Archiving Special Interest Group (PASIG) May 22-24 in Washington DC. PASIG is self-described as an “independent, community-led meeting providing a forum for practitioners, researchers, industry experts and vendors in the field of digital preservation, long-term information retention, and archiving to exchange ideas, identify trends, and forge new connections.” The PASIG meetings are critical to the future of preservation because, though the archival and tech worlds frequently work on parallel tracks concerning the same issues, there is a distinct lack of opportunities for conversation and sharing between them. Over the past few years the group has also taken an increased interest in dealing with the complexities of audiovisual materials.

At the meeting Kara will be a part of the Digital Preservation Bootcamp Panel speaking about Best Practices in Preserving Common Content Types for Media, along with a stellar group of digital preservation experts from Stanford University, Library of Congress, California Digital Library, and more. On Day 2 Chris will be a part of the Audiovisual Media Preservation Deep Dive panel discussing our new Cost of Inaction calculator. This analytical tool compares the money invested in reformatting magnetic media and the resulting extension of the media’s life against the cost of managing that media without making it accessible and, ultimately, losing it to decay or obsolesce within the next 10-15 years. Chris’ co-panelists will be Richard Wright (AudioVisual Trends), Dave Rice (City University of New York), and Mark Leggott (Islandora/University of Prince Edward Island).

As always there are a number of great panels and speakers planned, and we hope you’re able to make it this year or put the meeting on your radar for the next one. Chris and Kara are excited to attend PASIG to contribute and learn from others, so say howdy to them while you’re there.

How Do Archives Measure Up?

17 May 2013

Ask any archivist — or most anyone for that matter — what the importance of historical materials held by archives is and they will likely tell you that it is so large it is immeasurable, assuming that that is true and flattering. True, yes, to a degree, but definitely not flattering. In fact, that is one of the big problems with archives — that their value or impact is not directly measurable. We try to measure, and, despite the strength of the adverbs we use (very, extremely, critically, etc.), the measurement is soft because it lacks numbers.

Numbers. As a strict humanist I find numbers to be as much a faith-based system as any other, but they are what most people most easily grasp onto. Especially where money is involved. And that’s a big problem, because archives are cost centers — they take money and produce little direct revenue in return, even when they attempt to through licensing and other grasps at monetization. So instead we have to look to places where we can create numbers and generate reports to impress or prove that we are spending money wisely. This then boils down to number of patrons/requests, number of items/boxes, linear feet (ugh), and hours or Terabytes of content.

These numbers impress in one way (size matters), but we also have to prove productivity, which, unfortunately, has come to be measured by the number of finding aids produced and the number of linear feet processed within a given time. That helps give a sense that processing grants have been well spent, but, as I have argued before, does little to support preservation planning and creating access for audiovisual collections…Not to mention the fact that measurements such as linear feet give little sense to the number and length of a/v assets.

Not that these numbers don’t matter at all, because they do tell a particular story and different parties look to different measurements as meaningful. However, what they are focused on measuring is Return on Investment (ROI) — money in and money (or product) out. Really, though, what we should be looking at right now with audiovisual collections is COI — the Cost of Inaction.

How much are we losing content-wise and money-wise by not spending money on reformatting and other preservation activities? And is this measurable? Yes, it is. How many U-matics do you have in your collection? In 10-15 years those items and their content will be lost if they are not reformatted, and the money spent to store them and do any processing or management work on them all the years they’ve been sitting there will be a sunk cost. How many DATs do you have? How many VHS tapes? How many lacquer discs? How many 1/4″ audio reels? How many 1/2″ video reels? Those are numbers.

And really, this is the point we’re coming to with magnetic media, of measuring collections in terms of loss rather than in the number of assets and their use if we do not act soon. Those linear or cubic feet may remain (plastic takes a long time to go away), but the content will be irrecoverable, whether due to decay or the overwhelming cost to reformat it. I have to ask then, what is the ROI we’re giving to our culture if we let that happen?

— Joshua Ranger

Materialism, Morality And Media Culture

15 May 2013

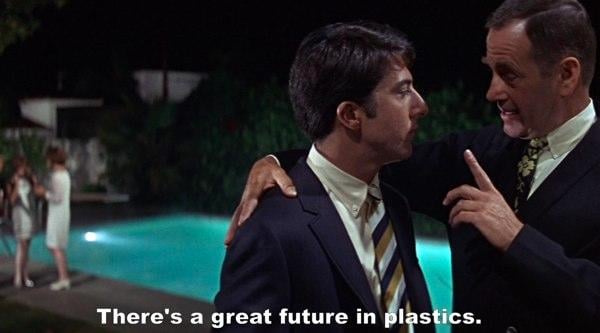

Plastics!

Film buffs know what this means. As in One Word. As in selling out one’s soul to live the life of a corporate middleman. As in a lifetime of creating cheap, soulless, synthetic replicas formed from deadly chemicals.

Film (and other media) buffs also ought to know what this means on a more physical level. As in plastics are a major component of the material object that we love. Plastic helps store the images and signals. Plastic helps transport the movements and sound through the decks and projectors. Plastic encases the hubs and reels, which themselves are often plastic.

Plastics!

So are we sellouts for worshipping plastic and chemicals, despite the warning we received from the past?

Well, apparently not so much, for it seems that digital has replaced plastics as the symbol of mass production and soullessness. In a recent blog post for Good Magazine, Ann Mack explores the analog countertrend to the digital era and decries the intangibility and inauthenticity of the digital as symbols of our fall from grace.

In Mack’s view the imperfection of physical objects makes them more real and more present to our lives than the slick perfection of digital devices. (I would ask if she has ever used a PC or an iPhone in order to review this idea…) The comparison morphs into an battle of real vs. fake. Fake is mp3s and streaming video and emails. Real is a live concert, handwritten letters, and vinyl LPs.

One could easily dismiss the gaps in logic and false equivocations as just part of the nature of blogging (I am not an unguilty party here.), but my sense is that this argument is representative of the general feeling out there around the digital vs. analog issue, as well as representative of how we conflate that issue with an assessment of cultural trends and moral judgement.

When we talk about our love for media there are three possible aspects we are referencing: the materiality and mechanisms of the physical object, the characteristics of the format that present themselves during playback, and the content itself outside of the object/format. One or many of these factors may be an influence on the viewer depending on their level of knowledge and engagement.

For those of us deep in the audiovisual production and preservation field this separation may not seem right. If we love one portion, shouldn’t we love them all for working perfectly in concert to create an experience? Love them all despite their flaws and physical or intellectual failures. And fail media does. Often. Often and often spectacularly.

But the complete formation of this golden triangle is seldom the case. This movie is awful but it was shot and distributed on VHS, so that makes it more interesting…This independent movie overcomes the flaws of how it was produced due to the performances and story…This movie is a minor classic but we’re seeing it projected on a nitrate print so that elevates it…This home movie is amazing but the original was so shrunken that it’s full of gaps and poor image quality…

Really though, these issues are incredibly academic and trend-based in nature. Delving down to that level requires an extreme knowledge and experience with film history that many people would not care about, but it is also linked to shifts in what a cultural moment considers valuable and relevant. This shifts back and forth from the new to the nostalgic, from the analog to the digital — though not all formats are considered equally within their respective categories (audiocassettes have a minor nostalgic following but will never be as respected as vinyl).

I find it interesting that the arguments Mack makes are largely about the experiential — the album cover, feeling paper, face time — and seem to mirror the studio arguments in the 50s on the superiority of the theatre experience over television. In either case this is a facetious argument because the format or experience is not a telling factor of the quality or purpose of the content, but more the individual’s reason or ability to select one experience over the other. A banal handwritten letter is still a banal letter. A film projected on a screen does not necessarily gain in aesthetic or intellectual quality purely due to that occurrence, or the fact that you were eating Goobers while watching it. (But, then again, Goobers.)

But this area of the format wars seems well trod and is not where my interest here lies. To chase a trend in order to explain it seems as frivolous as chasing trends to simply follow them. What I am concerned about is the moral judgement that this analog/digital divide gets saddled with. About the link of authenticity to physical media, to imperfection, and to time away from the screen as Mack puts it.

In and of themselves these are not bad things to be interested in, and neither are their opposites. Where I have a big question is whether we have been tricked into having an argument over the superior format of consumerism and branding. In Mack’s blog the positive examples are about growths in revenue and materialism. Does it really matter if one is purchasing a typewriter or a computer, a DVD or a movie ticket? And what about the moving line of nostalgia? Typewriters are old and cool, but it’s still mechanical and not handwritten. VHS was feared as the death of film, but now, perhaps because the threat was averted, it’s got more cache via nostalgia than DVD or streaming. Do the qualities of a material need to be perceptible to be of value (the grain of film, the touch of paper, the whir of the projector)? These sensual events do have meaning and value, but why is that more important than the intangible, indescribable, or worse, the inconvenient facts of materiality?

In the end, yes, the relative availability of formats or content is market driven, and that has an impact on our ability to preserve materials. But I wonder what happens when we internalize consumption as a point of advocacy or a valuative argument, and then merge that with the moral judgements we make on what and how other people consume. What does that do to our critical faculties, to what we are willing to accept or reject, to latch onto or overlook in our assessment and decision making? And do the results of that force us into a moral rigidity when we need to be much more plastic?

Plastics!

— Joshua Ranger

Chris Lacinak Presenting At ARSC 2013

14 May 2013

AVPreserve President Chris Lacinak will be attending and presenting on a panel at the 2013 Association for Recorded Sound Collections annual conference to be held in Kansas City, Missouri May 15th-18th. Kansas City is one of our favorite American cities, and its deep ties to the history of Jazz and Blues make it especially poignant location this year considering that an overriding theme of the conference will be discussion of the recently released National Recording Preservation Plan.

Chris will be on a panel with Josh Harris from the University of Illinois and Mike Casey and Patrick Feaster from the University of Indiana. The panel ties into the reports’s call to action by looking at three recent large scale census and inventory projects that are forming the basis of institutional preservation plans. Chris will be presenting on our work with the New Jersey Network (NJN) to inventory and provide a roadmap to preserve the 100,000 item program library that was left after the station was shuttered by the New Jersey government. For the project we used our new Catalyst software, a system we developed in-house that uploads multiple images taken of assets by on-site photographers to a centralized server, enabling an off-site cataloging team to create database records from the images remotely. The end result is a database containing both the images and metadata, enabling planning while mitigating the need and cost of accessing the physical materials until selected for reformatting.

Chris is excited as always to be participating in the ARSC conference, and doubly excited to publicly present Catalyst for the first time. We believe our new system can have a lot of impact on the ability to be proactive and more effective in preservation planning, and we look forward to getting feedback on it. Check out the panel and say hi to Chris if you’re not too busy having fun in KC.

Ray Harryhausen Is Cinema To Me

9 May 2013

Ray Harryhausen is cinema to me.

I use the term cinema and associate it with him because my love of the moving image was not forged in theaters but on UHF and early cable television. When I was 5 years old I was semi-disappointed one day when I thought I heard my mom say The Birds was on TV that afternoon, and it ended up being Thunderbirds Are Go. Semi-disappointed because Thunderbirds, Hitchcock, Universal horror, and the cannon of Ray Harryhausen were what captivated me at that time and what made me love the moving image.

I use the term cinema because, as a result of this, I was not tied to film projection as the sine qua non of the enjoyment of watching moving images. To me it is about the creation of illusion, about the frame. It is about the sense that just outside the frame are 30 people, backgrounds that would ruin the historical or geographic setting, and some crazy special effects guy pressing buttons and moving levers. It is about the sense that editing these pieces of film and variations in performance can create an infinite number of works spanning across genres. It is about tromp l’oeil and rear projection and prosthetics and matte painting and animation.

I use the term cinema because, really, for about half the lifespan of film, video and digital moving images have existed. However, though I know they are not easy, on a personal level I dislike CGI and 3-D because they seem easy. I enjoy the challenge and creative thinking that go into practical effects, the skill and mental trickery that give two-dimensional images depth and body.

I use the term cinema even though it sounds tiresome to say that cinema is illusion. But it is not an illusion in magical terms. It is illusion created from skill, imagination, coincidence, and the risk of gut feelings. The illusions often fail from the get-go, or they fail several years later when superseded by other technologies that appear more “real”.

I use the term cinema because it transcends time periods and formats. And though Ray Harryhausen’s techniques were superseded by newer technologies and newer approaches of storytelling, what he did was beyond that. What he did was the Homer and the Shakespeare and the Dickens of moving image. What he did was create a language that was so vernacular and specialized, so common and so unique that it seemed as if it had always existed. That it was an instant classic. That is was immediately something that any subsequent filmmaker had to copy, adapt, or work against.

I use the term cinema because it is the only high-falutin’ term we have for this type of thing, and because Ray Harryhausen has passed away, and because I wonder if I would be doing the work I do without the impact of the work he did. Work that enthralled me. Work that inspired me. Work that educated me and made me seek more. Wort that made me pretend to be sick so I could stay home from school and watch Jason and the Argonauts on the Bowling for Dollars Afternoon Movie.

Thank you, Ray.

— Joshua Ranger

More Podcast Less Process

5 May 2013

A 10-episode podcast series produced by AVP and METRO (www.metro.org) and funded in part by the New York State Archives Documentary Heritage Program.

More Podcast Less Process features interviews with archivists, librarians, preservationists, technologists, and information professionals about interesting work and projects within and involving archives, special collections, and cultural heritage. Topics include appraisal and acquisition, arrangement and description, reference, outreach and education, collection management, physical and digital preservation, and infrastructure and technology.

New Disaster Recovery Case Study By Kara Van Malssen

2 May 2013

AVPreserve Senior Consultant Kara Van Malssen has just published a new case study on the recovery of the Eyebeam Art+Technology Center collection post hurricane Sandy in October of last year. Almost the entire collection of video and file-based artworks and documentation was submerged in three feet of brackish, contaminated water during the storm, putting it at high risk of corrosion and irrecoverability if the items were not properly cleaned and dried within a few days. After Eyebeam put out a call for help, Kara, AVPreserve President Chris Lacinak, and Anthology Film Archive Archivist Erik Piil came in to perform triage, make a recovery plan, and help lead a volunteer team to implement the plan and stabilize the collection for future preservation.

Kara’s paper looks at the impact of the flood on the media items and lays out the plan and equipment used. Especially useful is pointing out the various pitfalls and tips of a recovery effort in a disaster zone: the difficulty in gathering supplies, contacting and organizing volunteers, maintaining consistent and easily communicated workflows to inexperienced or constantly changing volunteers, and acting quick and decisively while still keeping in mind safety of people and care for the materials.

In the weeks following the storm disaster preparedness was on everyone’s mind, well aware that after the second year in a row with a hurricane in New York we should start expecting it to happen again. But with time that mindset fades and we sink back to old modes. Besides imparting practical advice on how to run a disaster recovery effort, Kara’s paper should be a reminder that the best way to do that is to be prepared with a plan in place so that it does not take such an extraordinary effort. We were lucky to have such an outpouring of volunteer effort and resources semi-readily available, but that won’t always be the case in disaster zones.

Visit our Papers & Presentations page to download Kara’s paper (and other resources!) or go directly to the PDF of Recovering the Collection, Establishing the Archive. Also see Eyebeam Fellow Jonathan Minard’s video on the effort:

Recovering Eyebeam’s Archive from DEEPSPEED media on Vimeo.

Kara Van Malssen Featured Speaker At Screening The Future

29 April 2013

AV Preserve Senior Consultant Kara Van Malssen will be a featured speaker at the 2013 PrestoCentre Screening the Future Conference to take place May 7th and 8th at the Tate Modern in London, England. Screening The Future has quickly become one of the premiere media preservation events, with a strong focus on innovation, international efforts, and the pressing need to digitize and preserve our audiovisual cultural legacy. The theme for 2013 is Crossing Boundaries for AV Preservation, a nod both to the need in the field to push past technological and psychological boundaries we have set against moving into the file-based domain, as well as the need to collaborate with colleagues in different organizations and different countries to better solve the challenges of preservation and access.

Kara’s keynote on day two of the conference is entitled “When the ‘Worst’ Happens: How a disaster can change our perspective on the motivations and priorities for digital AV preservation”, looking at the motivations for digitizing collections along with considering the question of whether the quick triage decisions we make in the wake of a disaster can be similarly applied to regular collection management decisions. Kara will also be speaking on the focus session panel “Developing Solutions, Building Value” on the topic of open source tools for digital collection care. Other featured speakers include Matthew Addis (Arkivum Ltd.), Sam Gustman (USC Digital Repository and Shoah Foundation), Rob Hummel (Group 47, LLC.), Michael Moon GISTICS Inc.), Mark Schubin (SMPTE Fellow), John Zubrzycki (British Broadcasting Corporation), and many more. We strongly urge attending this important conference, and say hello to Kara while you’re there.

From the official press release: “Screening the Future is an annual showcase delivered by PrestoCentre and focusing on the latest technological trends in audiovisual preservation. This international conference brings together leaders in the fields of technology and research, and those with strategic responsibility for digitisation and digital preservation in the creative and cultural industries including broadcast, post-production, motion picture, sound and music recording, visual and performing arts. The conference aims to navigate participants through current case studies and latest thinking on standards and planning for the digital preservation of AV assets. Detailed programme will be available soon. For more information about the conference and registration please visit: http://2013.screeningthefuture.com“

Bert Lyons in “Preserving & Interpreting Born-Digital Collections” Panel

22 April 2013

On Monday, April 22, 2013, the Library of Congress National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program co-hosted the Rosenzweig Forum on Technology and the Humanities: Preserving and Interpreting Born-Digital Collections, as a special event in celebration of ALA’s Preservation Week 2013. The forum hosted four speakers to talk about how their institutions are addressing the acquisition and preservation of born-digital collections and a discussion of scholarly and research use of these unique collections.

The Elitism Of Film Preservation

10 April 2013

When I was studying some (and failing at) History as an undergrad (I don’t think the professors fully appreciated my approach of reading and interpreting historical texts as if they were literature) the full shift to the Bottom Up approach to the field was settling in. There was still time in class spent underscoring why that approach was important and why it was preferred, but I never got the sense that most students needed convincing at that point. It seemed that it was more just muscle memory spasms from the recent struggle of a paradigm shift away from a Top Down or Great Man approach.

In the old model history is told through the stories of leaders and powerful individuals (usually men) as if their decisions and actions were the primary causes or lessons to learn from. The Civil War as a story of politicians and generals, of singular accounts of hubris and honor, of a speech or a bit of blind luck or ill fortune that affected one man and turned the tide of battle. In the new model this is flipped over to view history as the story of the masses, of the underprivileged and commonplace as equal to the privileged and extraordinary. To continue our example, this method is well represented by the popular The Valley of the Shadow project that presents the Civil War as a story of everyday life, of soldiers and their families and their neighbors, of the farms and towns impacted by the war.

I was thinking about this topic after reading about Martin Scorsese’s recent National Endowment for the Humanities Jefferson Lecture where he spoke about the importance of film preservation. Despite his nominally Bottom Up supporting statements that all films should be preserved regardless of their box office results (the home movie and amateur circuits thank you, sir!) I came away with the distinct feeling that this was very much a Great Man view of media history. It seemed that the focus was on auteurism and Hollywood or otherwise distributed films. Or, Films.

To me this smacks of a hierarchical view of the moving image, one where Cinema is at the top, deserving of the most respect, the most resources, and the most concentrated effort (regardless of how much money it generated in release, of course). Though admittedly this would seem to include shorts, early cinema, and the avant garde — film productions influential on feature films if not of the genre itself — the summary of the speech does not seem to address the masses of amateurish and video productions that are out there (though I’m sure some people would group those two categories together…).

This bothers me in part because, despite a sympathy to the concept of the auteur’s vision, I am also too well aware of the huge amount of collaboration and serendipity that goes into film production, and a focus on the periodic or limited output of directors (or any specific creative/technical position) denigrates the roles of others in that process. It also bothers me because, despite the good work the National Film Preservation Foundation has done, their model and funding mission does not match the world of moving image collections as I experience them on the ground.

I do not see single films that require weeks of detailed work to restore them and garner front page articles in the newspaper. I see piles of U-matics and 1/2 inch open reel and miniDVs — thousands and thousands of them that need quality transfers, but are in a volume and state that would not be feasible at the same time and cost factor as a film preservation project. These are broadcast programs, interviews, field footage, news gathering, home videos, amateur image capture, production materials, and beyond. Box office doesn’t matter because there is no box office here. The auteur does not matter because these materials are more reflective of an institution or of related content produced over years and decades. It’s about the democratization and the speed that video capture enables, which also means that it’s about volume and long term impressions, not singularity and pristine objects.

Perhaps my anger is misdirected, because the frustration here is that video does not have the same foundational and federal support as film, whereas, arguably, video (and audio) is the much greater documentarian of history and culture of the past 30 years, documenting home life, political events, disasters, community, performing arts, and all degree of personal, regional, and national experiences.

I’m reminded of a project several years ago where we were discussing with the client the massive appeal/obsession with World War II footage and the relative lack of interest in more recent military events such as Grenada, Panama, Desert Storm, military response to natural disasters, etc. We lamented the fact that people were willing to let historical documents fade and decay because they were not sexy or “historical” enough, which, honestly is likely related to their nearness in time as much as the fact that recent events are on video while the Past is on film. The video was seen as less precious and less endangered (though if you want to find a Hi-8 PAL deck for me we can review that assessment).

Lest I misdirect you, this is not an argument over the comparative merits of film versus video. Both exist. Both must be cared for in the way that is best for them. Rather, it is an argument about historiography, about how we write, read, and interpret history. About the need to recognize now — not 200 years down the road — that history is currently being recorded on ugly formats in ugly ways with an entire lack of beauty and skill. Such is the human condition. Such is what we are tasked to care for.

********

Coda: But really, my biggest beef here is that Marty proclaims we should Save Everything. I mean, doesn’t he read my blog! Come on!

— Joshua Ranger