Select

Why We Fight

22 April 2011

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (City, that is) recently announced the successful restoration of an audio recording of a speech Dwight D. Eisenhower gave at the museum in April of 1946. General Eisenhower’s speech was part of the Met’s 75th Anniversary wherein he was being honored for his role in overseeing the protection and repatriation of monuments and artworks during and after World War II as performed by the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Section of the allied armies (MFAA).

The audio was recorded on glass-based lacquer discs — a highly fragile format that, like most lacquer discs, is at severe risk for chemical and physical degradation. Last year the Met received a grant from The Monument Mens Foundation, an organization dedicated to honoring the work done by the MFAA and continuing to support the protection and repatriation of art works in areas of armed conflict, to preserve the audio and make it accessible to the public. Our own Chris Lacinak was very honored to be one of a group of professional advisors who provided the Met with guidance on planning their restoration.

As always, it’s great to see a successful preservation project completed, and, going beyond Eisenhower, the story and (continuing) mission of the Monuments Men is fascinating, essential history. On a personal level, however, what this story brought back to me was a memory of what a scapegoat Eisenhower was when I was growing up — the middle-of-the-road, middle-of-America, caucasian patriarch who was the symbol of the hegemonic complacency our parents were oppressed with. Perhaps an exaggerated response considering the other forms of oppression occurring in the 1950s, but for years those too-brightly-lit, kinescope-distorted, early television images of Eisenhower in close up went hand-in-hand with scenes of mushroom clouds and children ducking under desks in various documentaries or other uses of stock footage.

But then something started to happen. Saving Private Ryan and The Greatest Generation made Boomers start to reconsider their parents’ lives. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq made people think about how the military is run and the president’s role as commander-in-chief outside the emotions caused by Vietnam. Eisenhower’s farewell speech, which included the warning about the military/industrial complex, became an ur-text of liberal politics. The past from my past became a different past as the interpretive position shifted from the heat of one moment to the glow of hindsight and the heat of another moment.

The cycle of generational context would suggest that I scoff at such softening as I continue to cling to my childhood anger at the dismantling of social, educational, and arts support in the 1980s. Reagan, too, has been making a comeback of late as both sides of the aisle fight over who best represents his ideology and his legacy. Either I’m a stubborn-headed fool or this is a good sign that I’m not too old yet.

A commonality in these parallel trends is the use of audiovisual materials to support reassessments — televised speeches, recorded visits of state, audio interviews — all of it easily distributable, easily accessible content. A commonality in this commonality is that, for the most part, one can assume these recordings come from major events covered by major news outlets. This is far from an assurance that such recordings would always be preserved, but, if they were, they would be and become part of the common cultural memory. Be because of the significant audience at the time. Become because of the repeated airplay they may receive in documentaries and news stories, a situation which can create a familiarity that causes people to believe they experienced the event the first time around…which then promulgates further reiteration of the same footage, becoming a visual shorthand for wide swaths of history. To half-misinterpret the old saw about Woodstock — if you remember being there you probably weren’t.

To me, this pseudo-echo effect has two meanings. First, audiovisual content is so powerful that it can embed itself in our memory quite easily. Second, we need to dig deeper with our support of smaller local, regional, or institutional archives and historical societies in order to uncover new stories that create a fuller picture of the past. The Eisenhower recording at The Met is a great example of this. DDE’s work with the MFAA, while incredibly important, has not been a major part of the wider representation of his military and political career. Thanks to The Met and the Monuments Men, we now have a greater understanding the career and the man.

One can also look to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting’s American Archive project, which is poised to uncover loads of locally produced programming that will be highly meaningful to our understanding of broadcast history and American culture, and as equally impactful to the pleasure we derive from both. Or among some recent clients I’ve worked with, one might look to institutions like Hartwick College in upstate New York whose archives contain a treasure trove of regional oral histories and audio or video recordings from the numerous scholars, artists, and cultural figures who have spoken at the college. Or the Tenement Museum‘s extensive oral history collection of Lower East Side residents, material that can be used to support research as well as the creation of exhibits and educational material which support the Museum’s mission.

It seems so common to repeat that humans and history are complex and deserve the full picture archival material can provide. Common, but worth restating because it is so easy to take for granted that archiving just happens, that of course everyone is taking care of their stuff because it is so valuable and that all that material is easy to find and use. Archiving is more than putting items in a box on a shelf. It requires active planning, management, advocacy, and promotion. As the MFAA and the military were aware, archiving and preservation do not happen unless we make them happen, unless we enable them to happen, unless we demand they happen. I reckon they were a might good generation after all.

Azimuth Adjustment For Magnetic Audio Recordings By Audrey Young And Peter Oleksik

14 April 2011

The ease of using cassette-based media — pop it in and press play — and the development of compact, no-frills consumer electronics helped make audiovisual materials more accessible to a wider population, but there has also been the side effect of distancing users from the processes involved in recording and playback that were more apparent with open reel media and higher end decks. This is less of an issue with commercially recorded tape where standards are more regulated, but when dealing with field recordings, oral histories, and other original material, the configurations and settings of the recording device and playback device can have a major impact on audio or visual quality if unaccounted for.

In the first in a series exploring all of those knobs, switches, and buttons you see on decks, Audrey Young and our own Peter Oleksik have written a brief primer on azimuth and why it matters for archivists, researchers, and other people who listen to or work with magnetic audio recordings.

Noting Screening The Future

12 April 2011

While our own Dave Rice was presenting on a panel at the recent Screening the Future symposium in The Netherlands, newest AVPS team member Kara Van Malssen was herself on hand to participate and learn. Here’s her review of the doings that transpired:

Screening the Future

15-16 March 2011

Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, Hilversum

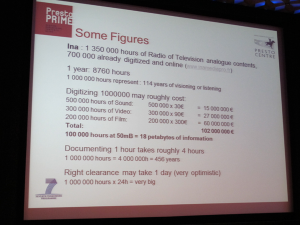

Screening the Future: New Challenges and Strategies in Audiovisual Archiving was an intensive two-day event on common challenges and solutions in the audiovisual heritage domain, held at the spectacular Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision in Hilversum. In a tightly packed schedule, 22 practitioners spoke on digitisation, workflows, digital preservation, sustainability, funding, improving access, and much more. The event marked the launch of the PrestoCentre, a new competence center for digital audiovisual preservation in Europe. A result of the successful European Presto project series (including the completed PrestoSpace and ongoing PrestoPRIME projects), PrestoCentre is a non-profit membership organization which will “provide analysis and advice to custodians and creators of audiovisual content, through online and offline services, publications and training.” There is already a wealth of useful information on their website, which is sure to grow into an indispensable resource for audiovisual archive professionals.

The conference celebrated the successful transition that many European audiovisual archives have made into the digital realm, while simultaneously sparking debate on the many ongoing challenges that these organizations still face: How can we valorize our archives? How can we fund ongoing digital preservation? How can we become more efficient? How should we approach the collection of the flood of born-digital (especially user generated) content that is not currently addressed by traditional heritage organizations? These are big questions, without simple answers.

There was quite a range of topics and speakers. However, given that it was a European event to celebrate European projects and progress, it was interesting to note that a large number of speakers were North American (or based in North America – such as the case of David Rosenthal, British, based in California). Also noteworthy was that only one woman speaker graced the stage over the course of two days (women, we can do better!). In any case, the expertise and experience of all the speakers was inspiring, and nicely balanced technical talks (like the presentation of new preservation planning tools from the IT Innovation Centre in the UK) with broad strokes.

Full presentation available here.

My personal top three presentations of the event addressed complex issues, sparked debate, and were energetic. I felt they left us with a charge, a task to improve, a direction to move toward.

———-

Peter Kaufman’s (Intelligent Television) keynote “Towards a New Enlightenment: Moving Images, Recorded Sound, and the Promise of New Technology” presented an overview of the landscape that audiovisual archives are entering as we move into the digital age, one in which audiovisual content is of equal or greater value than the textual asset (where, in fact, differences of media are evaporating altogether). Referencing Kevin Kelly’s new book, What Technology Wants, Peter whet the audience’s appetite with the notion that the millions of recorded sounds, images that archives are contributing to the web are fueling the electronic mind of the growing planetary electric membrane; we are contributing to the collective synthetic intelligence each time we give a name to an image online, or when we click a link. This global super computer is getting smarter everyday, and video is increasingly becoming part of that intelligence. With new tools like HTML5 and popcorn.js (live web citation and analysis of video content!), video is becoming a more integrated part of the web. There is enormous potential yet to come.

With that introduction, Peter offered 6 recommendations for the PrestoCentre, to help its members build together toward a “Digital Renaissance” – referencing the important recent publication by the European Comité de Sage – rather than a digital dark age. In sum:

- Engage our publics. Peter and Paul Gerhart have been working on this for the JISC-funded project, Film and Sound in Higher and Future Education. This is a marketing challenge, but one that AV archives cannot ignore.

- Engage with Technology. Make our content completely discoverable. Enabling resource discovery is a technical challenge, and involves applying relevant metadata. Users find that the range of user interfaces, search terms, and classifications make it difficult to find what they need. The commercial sector is exploiting the potential of recommendation engines (e.g. Pandora, Netflix). Can we learn from what they do? Google images can search automatically on rights embedded metadata. Wikipedia can crawl and ingest Flickr images that are Creative Commons-licensed. Peter’s recommendation: Develop a research and action plan for engaging with Google and other resources that make content discoverable.

- Facilitate use, clear rights. In order to achieve this, we must collaborate with current owners and their lawyers. Systematically set out the obstacles to making AV content available to education. Using new technology (like popcorn.js) we can actually identify rights holders, unions, and other contributors to a work, and…promote them! Give them credit where credit is due! A novel idea.

- Work with producers. Archival content begins as the point of creation. In the digital era, we can’t afford not to work with them.

- Work with business. Collectively determine best practices for public-private partnerships in AV heritage.

- And one bonus: Work with Americans! (We need your help!)

———-

Brewster Kahle’s energetic presentation, “Scaling Up, Scaling Down: Making the Most of What We Have,” on building cost effective digitization workflows and data centers for large scale digitization preservation had the audience hanging on to his every word (Brewster is certainly one of the most compelling speakers I’ve ever had the pleasure of listening to). His talk was framed around the work that has been accomplished by the Internet Archive (Millions of books digitized! The entire web archived!) on essentially a shoestring budget. Taking a bit of a jab at the Europeans, he pointed out that “large amounts of money give us excuses to not do things.” By focusing on efficiency and lowering costs, the Internet Archive is now able to mass digitize video at $15/hour and film at $200/hour. Off-air television is captured for very little, with Electronic Programming Guide and Closed Caption data extracted to improve searchability. He admits that it takes a lot of money up front to get started, but there are a number of ways to reduce costs over the long-term, such as leveraging the infrastructure of partners, and using your data center to heat your building(!). The Internet Archive measures its own progress in terms of bits in and bits out, and they are doing quite well: outbound they have 10 Gb/s of bandwidth being accessed by 2 million users each day. They are the 200th most popular site on the web, despite the fact that their “user interface is as bad as it gets.” The Internet Archive has so successfully built a cost-effective infrastructure that they can down offer cloud storage, at a cost of 1 terabyte for $2000….forever. That’s a one time payment folks.

Brewster had a lot to say about access as well. He discussed their business model, and how they are able to sustain themselves using a “free to all” access policy. He noted that, “archives make terrible business models,” and argued programs like digital lending are working, without getting the attorneys all heated up. He challenged the audience to think about their mandate as archives: are we just the preservation people, or are we the ones who are going to make stuff available on iPads? With a resounding “shame on us” he chided archives for keeping the best of what we have to offer in our basements, away from the reach of children who learn from what they can find on the Internet. We are not just archives anymore, we must be libraries too. Brewster is ready and willing to partner (for large scale data backup swaps), to offer services (digitization, storage, access), and he is going to do it cheaper and faster than most other organizations. His conclusion: “We get more done because we have less money than you.”

———-

The entire morning of the second day was a panel on “Building Workflows for Digitization and Digital Preservation,” which paired presentations from service providers (Michel Merten, Memnon; Jim Lindner, Media Matters) with representatives from some very large audiovisual archives (Daniel Teruggi, INA; Tobias Golodnoff, Danish Radio; Tom de Smet, Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision; James Snyder, Library of Congress). At first, I found it surprising that a large portion of the conference was devoted to digitization. After these talks, however, I realized that rather than a series of questions about the challenges of digitization, which has been the focus of many presentations over the past several years, these were digitization success stories: after years of trial and error, millions of hours of audiovisual heritage have been digitized. Something to be proud of, but we still have a long way to go.

Of these talks, I found Jim Lindner’s presentation on improving digitization workflows particularly useful. Jim’s simple argument is that by evaluating every point in the chain, by measuring bottlenecks, we can realized increased efficiencies. Sounds obvious, but turns out to be rarely practiced. Quite often, he finds that the problem isn’t where you might think it is, but perhaps further up the chain. Dependencies in the workflow mean you must untangle entire thing to find the problem, and then fix it.

Jim’s message is to take cues from the real world – security lines at airports, traffic, McDonalds – where efficiency is paramount. Business management and manufacturing literature can be particularly useful to the audiovisual sector. He recommended a number of books (Brussee’s Statistics for Six Sigma Made Easy, Womack and Jones Lean Thinking) but stressed that if you are just going to read one business book, make sure it’s The Goal by Eliyahu M. Goldratt’s (author of Theory of Constraints). Goldratt, and Lindner, press the need to look at the entire system, and identify the constraints, or bottlenecks. These are the places to measure things.

To illustrate the method, Jim used a typical audiovisual digitization workflow, which follows a process of accession → selection → digitization. Most archives perform selection because digitization is expensive, therefore, we shouldn’t digitize everything. But in this workflow, a backlog begins to form, and it isn’t at the digitization stage, where one might assume, but at the selection stage. Turns out, selection requires a surprising number of steps and individuals: choose tapes for selection; identify extant viewing copies, if any; generate viewing copies; view copy; catalog. If there is any bottleneck in this sequential process chain (unable to find copy, no machine to create copy), work stops proceeding. Thus, if we re-examine the overall goal, and look at the available tools to support the entire workflow, it might just make more sense to do the selection on the digital side.

———-

At the conclusion of the event, the moderator, Bernard Smith, along with Jeff Ubois, reviewed the conference themes, and asked the audience if we felt they were adequately covered. Do we know what we are preserving, and are we making the right choices? Have we developed good practices for working with the private sector? Do we have adequate funding models for sustainable digital preservation? Do we know how to best valorize our collections in today’s evolving landscape? The answer was a resounding NO. We have a lot of work left to do. Here’s hoping we’ll reconvene next year to revisit these issues and see how much progress we’ve made.

— Kara Van Malshttps://www.weareavp.com/team/kara-van-malssen/sen

AVPS Welcomes Kara Van Malssen

5 April 2011

AVPS is proud to announce the addition of our newest team member, Kara Van Malssen. Kara joins us from Broadway Video Digital Media where she was Manager of Archive Research on the Corporation for Public Broadcasting American Archive Strategy Consultancy. Kara is a 2006 graduate of NYU’s Moving Image Archiving and Preservation program, and she has held consultancies with CPB, National Public Radio, and the Museum of Modern Art, and previously worked as a Metadata and Digital Preservation Specialist in a joint project between NYU and public television broadcasters. She maintains strong interests in audiovisual preservation training and international outreach — having been invited to teach instructional sessions in Ghana, Mexico, India, and Lithuania — and also blogs on world cuisine at The Confined Nomad: Eating the UN, from A-Z, without Leaving NYC.

We have had the pleasure of working in tandem with Kara over the years on projects related to metadata development, digital preservation, and repository development, and we have always admired her skillz, strong character, outgoing nature, and wide range of personal interests. We’re extremely happy to have her join us now and look forward to the exciting opportunities ahead.

Archiving Ephemera — A Mini Manifesto (Semifesto)

21 March 2011

The lyrics for Talking Heads song “Love For Sale” were, according to David Byrne’s liner notes in Sand in the Vaseline, a not entirely successful attempt to write a love song using product or commercial tag lines. He has his own artistic reasoning behind his assessment, but from my point of view one problem is that he created a decontextualized archive of cultural information. I have plenty of peers that can cite all of the song’s references (and probably recite the entire commercial they originated from), but to my young nieces and nephews the lyrics would be empty containers that lack their purported meaningfulness. Similarly, I know plenty of 50-somethings that could recite commercial pitches from early television, and plenty of 70-somethings that can recall radio jingles and slogans from products that don’t exist anymore — all of which are meaningless reference points to subsequent generations unless footnoted in a scholarly edition of a period novel.

This begs the question of what the value is in the extensive archiving of such ephemeral, temporally-specific output. I like to think, I absolutely have to think in order to maintain momentum, that there is a value beyond kitsch or other forms of ironic re/mis-appropriation. I really hope my work is about more than saving audiovisual works with funny outfits and hairdos that people can giggle about or use in mash-ups. This is why I consider contextualization as an integral part of archiving. Despite the feelings of the general public, preservation requires a lot more than putting things online where they will “last forever”.

What, then, constitutes contextualization? There is the historical and there is the personal, and then there is where those converge. That convergence is key; neither strict historical nor strictly personal contextualizations can stand on their own as true pictures of the past. As Errol Morris suggests in his recent Times essay series “The Ashtray”, when we say that History (big H) is a social construct, we should not infer that to mean that history does not exist. It factually does. The methodology of History and the personal experience or interpretation of historical or otherwise time-based events are constructed from our own points of view and social milieu, and then degraded by the passage of time and the vagaries of memory.

The two sides establish a necessary balance between those Keatsian values of beauty and truth. History requires a degree of, not fiction — the division of fiction and non-fiction is too arbitrary and restrictive to be useful — but a degree of aesthetics or humanism. Both are truth: history is the truth of factual events and personal narrative is the truth of human experience. The context of both is required because an archive is not a resting place, but a living entity that can shift in meaning even as it does not change in content. Ephemera is not just material, but also speaks to the intangible, inconstant nature of memory, which must also be preserved.

As we lose context, we lose what ties us to the past and what moors us to humanity. The responsibility of archives to safeguard the tether to both is an essential function of what we strive to perform.

— Joshua Ranger

Embedded Metadata In WAVE Files

21 February 2011

Metadata is an integral component of digital preservation and an essential part of a digital object. Files without appropriate metadata lack the basic means required for computing systems and humans to understand, interpret, or manage them. Effectively, there is no preservation or meaningful access without metadata.

This presentation by Chris Lacinak covers the why, what and how of embedded metadata, focusing on WAVE audio files. It also reviews initial findings from an ARSC Technical Committee study, spearheaded by Chris, analyzing the interchange and persistence of embedded metadata across audio software applications that are regularly used in the creation of audio files in production and archival settings. Finally, Chris walks through BWF MetaEdit, a groundbreaking free and open-source tool commissioned by the Federal Agencies Digitization Guidelines Initiative and developed by AudioVisual Preservation Solutions in 2010.

Noirstalgia

17 February 2011

This post was written in support of the 2011 For the Love of Film (Noir) Film Preservation Blogathon. The Blogathon is a yearly event that helps raise money to preserve a film and also raise awareness of film preservation in general. This year’s film is the 1950 noir The Sound of Fury, directed by Cy Endfield and starring Lloyd Bridges. Donations that go directly to preserving this piece of cinematic history can be made at this secure Paypal site: https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr?cmd=_s-xclick&hosted_button_id=LAWFPAB4XLHAW. And great thanks to Blogathon hosts Ferdy on Film and The Self-Styled Siren. You can find more information about the blogathon on their sites as well as links to the blog posts from all of the participants.

That said, I have to admit I had a bit of trouble deriving a topic for this post. It isn’t that the theme is of disinterest to me — rather it is of too much interest. Noir is one of those areas of obsessive deep-diving I’ve covered in my free time. As a result I’ve seen several great films, a load of mediocre films, and more than my fair share of bad and/or disappointing films. So my problem is not apathy, but more a dilemma of the omnivore, of too many treats and too much desire. (Feels like I’m sounding like a noirish protagonist here…)

Where, then, does one start in such a scenario? Well, logically and filmicly I should start with a flashback to where it all started. If I think back on it, the first noir I saw was actually Chinatown. Depending on your level of zealotry, this could be considered more a neo-noir, or perhaps a derivative heap of tripe, but whatever the case, it wouldn’t be termed a “true noir”.

Or, in a sense, it actually could be. A common noir theme is the burden of the past — characters desperately trying to escape their past in conflict with other characters desperately trying to bring it back. The ex-con that can’t go straight; the one last heist and then we’re out for good; the amour fou that cannot be the same again; the life of coulda beens that just has to be this time…

In this sense, neo-noirs like Chinatown peddle in similar obsessions, albeit in a more meta manner. The burden of the past is not isolated to the story, but also extends to the filmmaking itself in the desire to slavishly recreate angles, lighting, story arcs, mis-en-scene, and other stylistic matters, as well as the obsession with clinging to the false memory of a when men were men and dames were dames society. Neo or non-traditional noir tries to escape this burden at times as well through creative re-imaginings, recasting of roles, or the use of unexpected settings. As we know from noir, however, the harder you work to unburden the past the more you cling to it — or it clings to you.

I was going to try and be (overly) clever here and dub this concept Noirstalgia, the obsession with a past, real or imagined, that eventually destroys you and your efforts. However, upon further consideration, I’m not so sure that plain old nostalgia itself couldn’t be defined in this same way by someone like Ambrose Bierce, and I moved on from this unnecessary neologism.

What these mental doodlings did make me think, though, was, man, I really wish preservation were this simple, that all we had to do was actively work at forgetting a film and it would therefore naturally persist in order to haunt us. This got me thinking about the climax of Fahrenheit 451 where the bombs are going off and the characters are recalling — verbatim — books they had read. This scene has stuck with me perhaps more out of wonderment than anything else. I have a terrible memory for books, dialogue, lyrics, etc. I can listen to a song 157 times (Thanks for keeping track of how lamely I waste my time, iTunes!) and still not be able to recite lyrics except for a nanosecond behind real time while listening to it. The end of Fahrenheit 451 may be a powerful image, but it’s incomprehensible to me as a denouement, and I still obsess about how it could be possible.

In truth, noir is a highly stylized genre (okay, okay, if it really can be considered a genre), and cultural memory tends to work more like my own — without an immediate presence or other triggers, the materials we value so dearly are quickly forgotten or replaced by newer distractions. We have to struggle to preserve that past not so that it consumes us, but so that it is not consumed and destroyed by physical and memorial degradation. So support the efforts of For the Love of Film and of all the audiovisual preservation efforts across the globe that are required to maintain our cultural heritage so that we’re not tempted to stray back off into our dark past.

— Joshua Ranger

Things That Shouldn’t Be Archived #8 — Valentime’s Edition

10 February 2011

Because “Love is in the Air” (1979)…

Portions To Be Archived: Skilled house bands

Portions To Not Be Archived: The idea that Tom Jones needs show girls to be interesting; Disinterested cover songs based on lazy, cliched selection process

Portions To Be Archived: Knowledge that if you take care of your body it will take care of you; Knowledge of the great electronics available in Argentina

Portions To Not Be Archived: Potentially world-destroying amount of sexy on one stage — remember the lessons of multiple copies in geographically separate locations

Portions To Be Archived: Crazy musical production numbers

Portions To Not Be Archived: Crazy musical production numbers; White jump suits and levers; Pirate shirts

Portions To Be Archived: Those moves!

Portions To Not Be Archived: My former memories of Mr. Jones in concert (circa mid-90s) as not so spry

— Joshua Ranger

Getting Out Of The Fog

3 February 2011

I had a mildly indulgent movie-watching weekend, having gorged on two DVDs (John Carpenter’s original The Fog and the first disc of The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr. — I am not a prideful man.) and one theatre-going experience. I wouldn’t say that three flicks in one weekend is indulgent — there have been times where that was an average day (I am not a prideful man.). What was indulgent was taking the time to listen to the audio commentary on both DVDs, something that I rarely ever do (Okay, now I am a prideful man).

I dig the whole film-school-in-a-box concept that a stack of DVDs plus audio commentaries is a useful learning tool, but maybe for the same reason I’ve never cared for reading scholarly introductions to novels I’m just not that into it. Or, likewise, maybe I’ve been too influenced by the insightfully codified breakdown of Commentary Tracks of the Damned to have much patience with them.

Of course I’m not a total curmudgeon (or pretend not to be) and do enjoy certain commentary tracks. I will always listen to the likes of John Waters and Werner Herzog, and I have a special affinity for listening to the filmmakers, producers, and crew members from older B-movie and horror films discuss all the tricks and workarounds they had to figure out in order to overcome lack of funds, inadequate equipment (and sets and actors), and other roadblocks of low budget filmmaking. I just happened to hit the perfecta this go around in the chance to listen to John Carpenter and Debra Hill discuss the struggles and solutions in making The Fog as well as to the handsome, handsome raconteur Bruce Campbell.

An interesting convergence between the commentaries was a repeated focus on the differences between filmmaking and special effects in the past and contemporary, primarily digital processes. For Bruce Campbell (and series producer Carlton Cuse) these musings are more about nostalgia and appreciation for a filmic past. They point out various shots and props that would now be created with green screen or CGI effects rather than with miniatures, foam, location shoots, and optical trickery, but equally important to them is waxing poetic about the connections their production had to old Hollywood. They put forth that they were likely the last people to use certain Western sets and ranches that are probably housing developments today, and they are proud and feel lucky to have employed the actors, stuntmen, horse trainers, gun wranglers, and other crew that had been working on films and television shows for 40+ years and were at the tail end of solid careers.

Carpenter and Hill have a similar gee-whiz-look-what-we-did attitude — perhaps even more so since they appear to have had a lower budget for The Fog than the Brisco County pilot episode did — but there’s a certain tinge of sadness to their reminisces. Campbell and Cuse have a dang-we’re-lucky nostalgia for film history; Carpenter (and maybe Hill) seem to have an elegiac nostalgia for their own past, a period of their lives when they were young and energetic and driven to succeed at all costs, when creativity came easy and the critical plaudits flowed from alternative and mainstream interests alike.

I’m not sure I can rope Hill in here — she went on to a great degree of success as a producer and as a pioneering woman in Hollywood executive circles — but, in spite of some secret-success-upon-reassessment films*, Carpenter realized very little widespread accolades after Starman in 1984, only 4 years after The Fog. He would seem to have a much greater feeling of loss for the successes of his youth

*No knock on Carpenter here — I’ve always been a fan of Big Trouble in Little China and They Live, and Cigarette Burns is one of the best Showtime Masters of Horror I’ve seen.

Carpenter’s lament very much seems to follow the pattern set out by Raging Bulls and Easy Riders — the young, innovative, Nouvelle Vague-ish director who, with significant support from a female work and/or life partner, makes some revelatory low budget early films, transitions to bigger budget studio fare and, at some point, ditches the woman and makes a bloated, ego-driven project that is seldom fully recovered from.

I realize it isn’t entirely fair to psychoanalyze Carpenter from afar, but as an English major from the 1990s focused on authors from the 1790s, such was my training. I will say, though, that this is nothing personal. Or, rather, it is deeply “personal” to me. What I’m interested in here is how one maintains one’s motivation through success, ease, and beyond.

There is a fascinating side note to the research Mark A. Greene and Dennis Meissner did for their landmark article “More Product, Less Process: Pragmatically Revamping Traditional Processing Approaches to Deal with Late 20th-Century Collections”. While analyzing processing times per cubic foot of (paper) archival materials, they found that institutions which received large processing grants had significant drops in processing rates. Significant as in going from averaging around 150 feet a year to around 50 feet a year. In the authors’ experience, spending $200 per foot in staffing and supplies was not unusual, but according to NHPRC records grantees often spent over $500 per foot on processing projects.

Greene and Meissner are puzzled at such actions and ponder the reasons, whether it might be that an influx of resources makes institutions let their foot off the gas a bit or whether the institutions focus in on detailed item-level processing rather than using the windfall to cover more materials at a higher level. It’s hard to know the reasons for sure, but the situation is reminiscent of the typical Walk Year scenario in professional sports: In the final year of a contract an athlete who had some early success but has dropped off a bit in production suddenly regains their fire and has a career year. Come the off season they get a long-term monster contract based on that season and, very often, immediately settle back to the former trajectory of complacency or late-career decline.

This is not to suggest archives are complacent (nor in decline) — a 9-month contract cataloging gig does not set one up for life like a guaranteed $80 million — but rather this is a consideration of the initial hurdles to implementation and the ups and downs of long term efforts that must be managed intelligently in order to achieve or sustain success.

The backlogs of work related to audiovisual preservation and the resources required to perform that work are significant, which is why it is so necessary to continue to develop innovative and efficient approaches to that work. I love cinema for the stories and visuals, but I also love it because I am inspired by the kind on innovation directors like Carpenter (or cinematographers, effects crew, etc.) use to take a vision from their heads and make it appear on screen. I’m lucky enough to get to see a number of archives use that same drive and creativity to achieve their goals, and lucky enough to work on those kinds of solutions as well…Hopefully in a way that will make the commentary track to my life a bit more interesting down the road.

— Joshua Ranger

David Rice Screening The Future

31 January 2011

AVPS Senior Consultant David Rice has been invited to speak at Screening the Future 2011: New Strategies and Challenges in Audiovisual Archiving to be held at the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision March 14th and 15th. Screening the Future is being produced by the European Commission-funded Presto projects, a series of initiatives working to “develop solutions to preserve audiovisual content and provide services to share knowledge regarding audiovisual preservation”. The event will mark the launch of PrestoCentre — a self-sustaining continuation of the Presto projects — and participants “will help set the agenda for AV preservation in Europe, and benefit from interacting with leading institutions, funders, vendors, and policymakers”.

David will will be speaking with Skip Elsheimer (A/V Geeks) on the panel “Introduction to Transcoding: Tools and Processes”. From the programme description:

- “Digital formats evolve over time. This session will demonstrate the basics of transcoding and the utilities, strategies and challenges involved in efficiently providing access to digital audiovisual media collections. It will examine software-based tools and applications, identifying what to look out for, how to evaluate lossless and lossy transcoding methods, quality control, and verification.”

Those of you who have seen David’s and Skip’s Digitization 101 panels at the past several AMIA conferences know they are highly informative while also being highly entertaining and accessible to a wide audience, opening up the seemingly obscure world of digital video and audio in a way that is as tangible and revelatory as inspecting a film by hand. David has been developing some new avenues of investigation to discuss about transcoding, so this should be another great presentation.

Other speakers over the two days include Brewster Kahle (Internet Archive), David Rosenthal (LOCKSS, Stanford University), Jeff Ubois (PrestoCentre), Matthew Addis (IT Innovation), Richard Wright (BBC R&D), Peter Kaufman (Intelligent Television), Marius Snyders (PrestoPRIME Project), Jan Müller (Managing Director, Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision), Paul Miller (Cloud of Data), and Seamus Ross (Faculty of Information, University of Toronto).

Full details and registration information can be found at http://screeningthefuture.eventbrite.com/

Also see

PrestoPrime http://www.prestoprime.org/

and

Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision http://instituut.beeldengeluid.nl

for more audiovisual preservation information.