Article

The DAM AI Gap Is Real. Here’s How to Close It.

15 January 2026

The fastest way to tell if your DAM is (un)healthy is to turn on AI.

Because AI does not just make DAM smarter. It makes your DAM’s foundations visible. When the fundamentals are strong, AI accelerates what is already working. When the fundamentals are weak, AI amplifies inconsistency, risk, and cleanup work.

That matters because organizations are being asked to do more with less, and AI has become the default answer. DAM is no longer expected to be a repository. It’s expected to orchestrate content operations, reduce friction, and scale output. But without consistent metadata, clear governance, and operational control, AI can’t deliver that promise. It amplifies whatever is already true in your DAM, including gaps.

AI is proliferating across the DAM ecosystem. Vendors and DAM-adjacent platforms are shipping automated metadata creation, natural language search, and agentic AI at an unprecedented pace. Leaders within organizations are being told to expect dramatic gains in efficiency, automation, and discoverability, often framed as the fastest path to doing more with less.

But a consistent reality is showing up across organizations: many do not yet have the foundations, funding, or control required to leverage AI safely and effectively.

This is what I’m calling the DAM AI Gap: the disconnect between what AI promises and what most DAM programs are actually ready to operationalize.

If you are not seeing results from your DAM or early AI initiatives, it is likely not a technology problem. It is a foundation problem.

The good news is that this gap is solvable and often faster to address than leaders expect when the work is approached with the right experience and a clear path.

The Gap

The pattern is straightforward. Market innovation is moving faster than organizational readiness. Advanced AI capabilities assume a level of maturity that many DAM programs have not yet achieved. Most organizations are still constrained by fundamentals:

- Inconsistent or missing metadata

- Weak or unclear governance and ownership

- No taxonomy or competing taxonomies

- Fragile workflows and uneven adoption

- Half-baked integrations that keep content scattered across systems and shared drives

- Disorganized ecosystem

The ambition is DAM as a system of action, not storage. The reality is uneven data quality, under-resourced teams, and unclear control points. The risk is that AI and automation amplify weakness rather than resolve it.

AI does not replace DAM fundamentals, it depends on them. When the underlying structures are not in place, AI-driven features often create new failure modes. Improved discoverability without strong permissions and rights management can expose content to the wrong audiences.

Automation without oversight can scale mistakes faster than teams can catch them. AI layered onto fragile governance can create noise and unpredictability, which erodes trust and adoption.

In our 2026 DAM Trends survey, the tension was clear: the vision is compelling, but the fear is being pushed to move faster than governance, data quality, and operational control can support.

Most organizations are operating under sustained efficiency pressure. DAM, marketing operations, and content operations teams are being asked to deliver more impact with constrained capacity while also adopting new AI-driven capabilities.

In that environment, the foundational work AI requires is often the first work deferred. Metadata models, taxonomy decisions, governance structures, rights and permission frameworks, workflow integrity, integration design, enablement and operational ownership are hard to prioritize when teams are stretched.

The result is predictable: the organization invests in AI and automation expecting speed and savings, but experiences more cleanup work, higher risk exposure, and slower adoption. Not because the technology failed, but because the operating foundation was never built to support it and accordingly there were unreal expectations of what AI could do.

This is not a story about resistance to change. It is a story about organizations knowing what DAM needs to become and being acutely aware of what can go wrong if they try to get there without fixing the fundamentals.

Closing the Gap and Delivering on the Promise of AI

At AVP, we embrace the potential of AI, but our stance is grounded in truth and readiness.

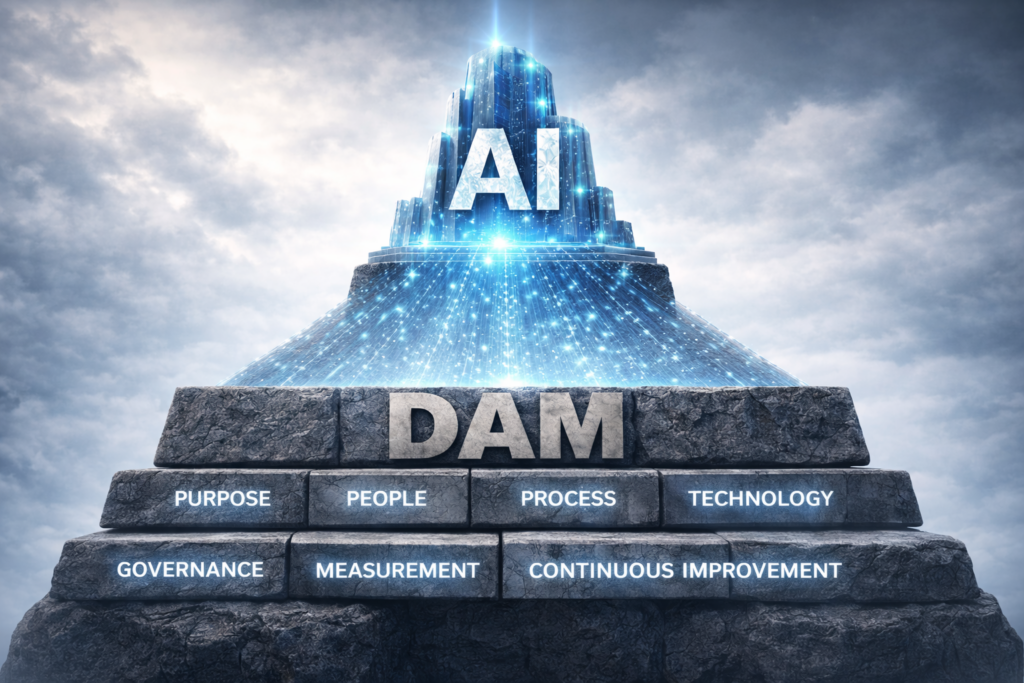

AI can amplify DAM value, but only when the foundations are sound. If you want to unlock the power of AI, you have to get the foundation in place first. Much of that foundation is what we define as the DAM Operational Model: the operating system that makes DAM sustainable and scalable across people, process, governance, and technology (Learn more about that here.)

Without it, AI becomes another layer of activity on top of instability, rather than a multiplier of value.

This includes things like:

- A metadata model and taxonomy aligned to how the business finds, governs, and uses content

- Clear governance, ownership, and operating mechanisms that sustain quality over time

- Permissions, rights management, and policy controls that protect the organization as discoverability improves

- Workflows and practices that scale across teams and regions

- Integrations that support end-to-end operations, not isolated repositories

When these fundamentals are in place, the outcomes leaders are looking for become achievable:

- AI works as intended

- Automation becomes reliable

- Rights and intellectual property are protected

- Workflows scale and cycle times drop

- Adoption increases because teams trust the system

- ROI becomes visible and defensible

If your organization is under pressure to move faster with AI, the highest-leverage move is to treat DAM fundamentals as an executive-level capability, not an operational nice-to-have.

That framing also gives DAM practitioners the language they need internally: the work is not “cleanup.” It is risk mitigation, preparedness, efficiency enablement, and value realization. The goal is not to slow down AI. The goal is to make AI safe and effective.

AVP helps organizations close the DAM AI Gap by building the foundation required to make AI safe, scalable, and ROI-driving. We provide the expertise and capacity to:

- Build or rebuild taxonomy and metadata structures

- Establish governance, permissions, and rights management

- Fix workflow and operational bottlenecks

- Stabilize underperforming DAM environments

- Support lean or capacity-constrained teams

- Integrate AI safely and effectively

If you are not seeing the results you expected from DAM or early AI initiatives, start with readiness. Close the foundational gaps that determine whether AI becomes a multiplier or a liability.

Work with AVP to build the DAM foundation that enables safe deployment, scalable operations, and defensible ROI.

DAM delivers on the promise of AI. AVP delivers on the promise of DAM.

Let us know how we can help you.

Trust, Authenticity & Governance for the AI Age

1 December 2025

Trust is hard to come by.

Eminem

Technology succeeds when it is leveraged to transform data into information and then information into insight that can then generate action and meaning. Collective actions build mutual trust among community members, establishing knowledge-sharing opportunities, lowering transaction costs, resolving conflicts, and creating greater coherence. Trust sets expectations for positive future interactions and encourages participation with technology. Communicating the meaning and purpose of why a technology tool is being used will build trust with its audience and impact positive experiences. Trust in technology and the data flowing through all connected systems will lead to greater participation that will increase information’s value and utility. But is artificial intelligence (AI) in our content, our documentation, and our marketing information is making this all the messier and more complicated? The question is, do we trust what we see and read?

AI as an energetic force for change in our modern business content systems such as a DAM, PIM, CMS, and e-Commerce will accelerate the conversation between business and consumer. All the integration and interconnectivity between business applications strengthens the argument for strong and authoritative metadata, and for effective workflow management. Businesses creating and disseminating brand and marketing messages and products will engage with the consumer community who will respond with shopping behavior, internet searches, assets, and data such as reviews, comments, images, check-ins and other online actions. Data serving content as a connection between people, process, and technology.

Furthermore, understanding the needs of users and showing transparency in the technology, the people and the process will improve the experience and start the path to building trust. And yet, trust is hard to come by because there is not enough of it in our data. It’s no surprise that some of the biggest and most vocal critics of AI are artists themselves, the creators, those who create from an original and inspired source.

“I hate AI … AI is the world’s most expensive and energy-intensive plagiarism machine. I think they’re selling a bag of vapor.” – Vince Gilligan

“People ask if I’m worried about artificial intelligence, I say I’m worried about natural stupidity?” – Guillermo del Toro

And we are beginning to see more criticism from the creative community of AI being used in marketing the most recent of which is the negative feedback on Coca-Cola’s 2025 Christmas ad which follows criticism of their 2024 efforts. This in tandem with the persistence of “AI hallucinations” gives us all reason to pause and query where the trust and authenticity is in our content. Should consumers be skeptical … yes, but if we start to “distrust” what we see, then uncertainty creeps into the relationship. A 2024 study by Bynder found that when posts sound AI-written, 25% of people think the brand feels impersonal, and others flat-out call it lazy. Trust is getting harder to come by in a world filled more with hyperbole than facts, precision and nuance.

Let’s get some definitions out of the way to help both ground and illuminate this discussion:

Authenticity – The trustworthiness of a record as a record, i.e., the quality of a record that is what it purports to be and that is free from tampering or corruption.

Provenance – The origin or source of something. Information regarding the origins, custody, and ownership of an item or collection.

Integrity – The quality of being honest and having strong moral principles; of being whole and complete.

Data Integrity – The property that data has not been altered in an unauthorized manner; in storage, during processing, and while in transit.

What’s your data-driven AI strategy? We want the data and the machines managing it to learn and do more, but we must provide them with good, quality data for them to do that. Good data = smart data = good learning = happy customers. But if the data delivered does not match the user expectations, then the efficiencies of a personalized, and meaningful consumer experience are lost. Do we trust what we see and read? Data is the foundation for all that organizations do in business and how they interact with their customers. Data is proliferating, and that growth is only going to continue exponentially. As it multiplies, organizations need refreshed, enterprise-level approaches to systematically create, distribute, and manage data for your brand and your customers. Is authentic, accurate, and authoritative data the foundation to help us navigate the digital age?

Information Integrity

“Transparency builds trust.”

Denise Morrison

Data provides the link allowing processes and technology to be optimized. But if the data delivered does not match the user expectations of accuracy and authenticity, trust may be lost. Trust may not always be built with consistency if the facts are not always there. Be mindful of the current situation and the challenges faced. More importantly, be mindful of the people, processes, and technologies that may influence transformation. Information, IP and content are critical to business operations; they need to be managed at all points of a digital life cycle. Trust and certainty that data is accurate and usable is critical. Leveraging meaningful metadata in contextualizing, categorizing and accounting for data provides the best chance for its return on investment. The digital experience for users will be defined by their ability to identify, discover, and experience an organization’s brand just as the organization has intended.

Integrity of information means it can be trusted as authentic and current. When content is allowed to move freely, the chain of custody can be lost, undermining trust that the information is original. By establishing rules around originality and custodianship, or document ownership, content can be relied on as the “single source of truth,” and there may well be more than one source of truth, for it is authenticity we seek. As an example, if we define content as something that has value to the organization, then controls should be placed on access to that content. If controls are not in place, or they are insufficient, then the consequences can be embarrassing and costly. Possible dangers might include having the company sustain damage to its reputation, or it could result in the loss of trust of clients or consumers.

History teaches us that the study of “Diplomatics” in Archival Studies, posits that a document is authentic when it is what it claims to be. The Society of American Archivists (SAA) definition reads, “The study of the creation, form, and transmission of records, and their relationship to the facts represented in them and to their creator, in order to identify, evaluate, and communicate their nature and authenticity.” And, with that definition comes arguably its greatest modern proponent of Diplomatics, Luciana Duranti, reminds us to be mindful of, “the persons, the concepts of function, competence, and responsibility” must all be considered when considering digital assets and trust, from creation to distribution. Trust in content created with authority, authenticity, and responsibility.

Governance is No Longer an Option

Governance is the process that holds your organization’s data operations together as you seek to become truly data-driven, realize the full value of your data and content, and avoid costly missteps. To be effective, governance must be considered as a holistic corporate objective establishing policies, procedures, and training for the management of data across the organization and at all levels. Without governance, opportunities to leverage enterprise data and ultimately your content to respond to new opportunities may be lost. By developing a project charter, working committee, and timelines, governance becomes an ongoing practice to deliver ROI, innovation, and sustained success. While technology is important, culture will prevail, for Governance is more than just “change management”. Governance demands a cultural presence and footprint. The best way to plan for change is to apply an effective layer of governance to your program.

In his autobiography, Permanent Record, Edward Snowden argues that “Technology doesn’t have a Hippocratic oath. So many decisions that have been made by technologists in academia, industry, the military, and government since at least the Industrial Revolution have been made based on ‘can we,’ not ‘should we.” Another example of governance is needed is reflected in the advice of moving away from the brash work ethic of “move fast and break things,” from millennial technobrat and Cambridge Analytica whistleblower Christopher Wylie, who argues for a “building code for the internet” and a “code of ethics”—in essence, regulations to prevent the technological atrocities of the past. Governance is about the ability to enable strategic alignment, to facilitate change, and maintain structure amidst the perceived chaos.

Good governance delivers innovation and sustained success by building collaborative opportunities and participation from all levels of the organization. The more success you have in getting executives involved in the big decisions, keeping them talking about AI making this a regular, operational discussion (not just for project approval or yearly budget reviews), the greater the benefits your organization will have. Participation from all levels of the organization is key. Engaging the leadership by involving them in the big decisions, holding regular reviews and keeping them talking about DAM or any content management system, will yield the greatest benefits.

Opportunities to Provide Authenticity

From a legal point of view, there is some hope for the future as new legislation regarding AI creation and usage does take into account issues of “transparency” and “provenance,” most notably in the new California Transparency Act (AB 853) (SB 942), and the Transparency in Frontier Artificial Intelligence Act (TFAIA) all coming into effect in 2026, with the EU Artificial Intelligence Act been in place since 2024.

From a practical point of view, there are some things we as digital creators and managers of content may do:

- C2PA, Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity, provides an open technical standard for publishers, creators and consumers to establish the origin and edits of digital content at the metadata level. This also includes Content Credentials to leave a metadata audit trail for your digital assets (e.g. date, time, and location of creation, along with a digital signature to prove authenticity)

- Employ embedded digital signatures and watermarking.

- Implement AI detection to identify if an image, video, or audio file has been altered or generated by AI.

- Quality control and data verification on a regular basis throughout the digital asset life cycle to ensure content came from trusted and authorized sources.

- Governance as an organizational process to mitigate risk and to achieve your goals.

Amidst the clash and clatter of AI it is good to know there are real tangible things you can start doing to use people, process, technology and data to navigate this complex environment.

Conclusion

Good, trusted, authentic data is critical to AI; trust and certainty that the data is accurate and usable is critical for success. And be mindful of the people, processes, and technologies that may influence data and learning within business. Data will only continue to grow. There has never been a more important time to make data a priority and to have a road map for delivering value from it. AI provides great opportunities for communication, engagement, and risk management. Data sharing and collaboration will play an important part in growth, as business rules and policies will govern the ability to collect and analyze internal and external data. More importantly, business rules will govern an organization’s ability to generate knowledge—and ultimately value. To deliver on its promise, data must be delivered consistently, with standard definitions, and organizations must have the ability to reconcile data models from different systems.

A call to action … may we all just slow down. Simple, and effective. Yes, AI is incredible and powerful and advancing at a fast pace, which is exactly why we need to slow down as best as we can. Remember to evaluate your trusted sources of information and evaluate what you are reading. Trust may not always be built with consistency if the facts are not always there. Be mindful of the current situation and the challenges faced. More importantly, be mindful of the people, processes, and technologies that may influence transformation. Information, IP and content are critical to business operations; they need to be managed at all points of a digital life cycle. Trust and certainty that data is accurate and usable is critical. Leveraging meaningful metadata in contextualizing, categorizing and accounting for data provides the best chance for its return on investment. The digital experience for users will be defined by their ability to identify, discover, and experience an organization’s brand just as the organization has intended.

While metadata may help us find the facts needed for that truth, governance is the structure around how organizations manage content creation, use, and distribution and a critical part to developing trust. Ultimately, governance is the structure enabling content stewardship, beginning with metadata and workflow strategy, policy development, and more, and technology solutions to serve the creation, use, and distribution of content. Content does not emerge fully formed into the world. It is products of people working with technology in the execution of a process… the transparency needed for content to be authoritative, authentic, and all willing, responsible. Trust may be built through transparency and quality data, and trust may be earned through good governance; your brand depends upon it.

Citations

- https://variety.com/2025/tv/news/pluribus-explained-vince-gilligan-rhea-seehorn-1236571666

- https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/guillermo-del-toro-not-worried-artificial-intelligence-1235585785/

- https://www.creativebloq.com/design/advertising/what-brands-can-learn-from-coca-colas-terrible-ai-christmas-ad

- https://www.bynder.com/en/press-media/ai-vs-human-made-content-study/

- https://interparestrustai.org/terminology/term/authenticity

- https://dictionary.archivists.org/entry/provenance.html

- https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/integrity

- https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/data_integrity

- https://calmatters.digitaldemocracy.org/bills/ca_202520260ab853

- https://calmatters.digitaldemocracy.org/bills/ca_202320240sb942

- https://www.gov.ca.gov/2025/09/29/governor-newsom-signs-sb-53-advancing-californias-world-leading-artificial-intelligence-industry/

- https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/

Choosing a Digital Asset Management System: The Final Decision

27 August 2025

After months of evaluating platforms, the moment has arrived: it’s time to make a decision on your digital asset management (DAM) system. Your choice will shape how your teams access, manage, and use content for years. Our goal is to help you move forward with confidence.

We assume you’ve already done the necessary legwork: aligning stakeholders, identifying requirements, evaluating right-fit vendors, and running demos and a POC tailored to your assets and workflows. If not, consider revisiting those steps—take a look at our previous posts in this series.

Reconnect with Your Digital Asset Management System Goals

Before comparing feature lists or pricing tables, revisit why you began this process. What problems are you trying to solve? What does success look like a year from now? Make sure your final decision is rooted in those goals. Your task is to choose the digital asset management system that best supports your organization, not just the one with the flashiest interface.

Evaluate DAM Vendors Using a Structured Framework

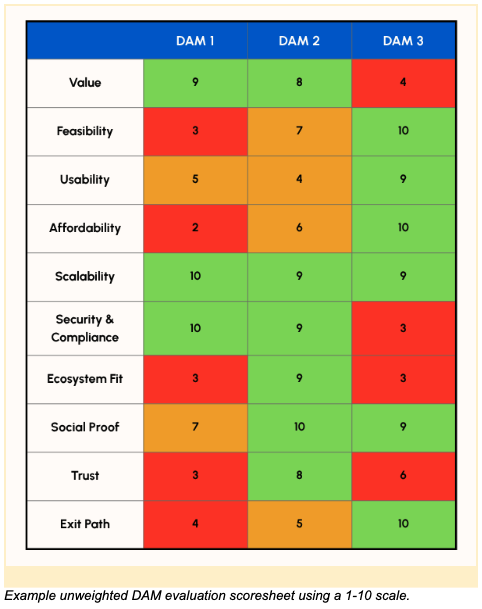

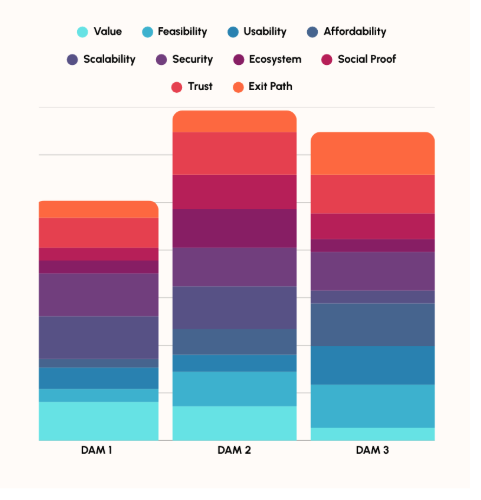

A decision of this magnitude benefits from objectivity. Using a structured scoring model or decision matrix can help your team make a transparent, evidence-based selection. This approach allows you to evaluate each platform against consistent criteria, assign weights based on your priorities, and compare options side by side. It also creates documentation that supports internal alignment and future reference.

Ten Dimensions to Evaluate Each Digital Asset Management System Vendor Finalist:

1. Value

Does the platform deliver the functionality you need? Does it offer capabilities that significantly improve how your organization produces, manages, and shares content? Focus on alignment with your current and future needs, not the total number of features.

2. Feasibility

Can you implement and maintain the platform with your available resources? Consider implementation effort, integration complexity, and ongoing management. A great-looking system may require infrastructure or capacity you don’t currently have.

3. Usability

How easy is the system for different user groups—admins, content creators, and end users? If these groups weren’t included in demos, or didn’t participate in a proof of concept, go back a step. Be sure to get input from the people who will be affected most. Don’t forget to test admin functionality too.

4. Affordability

Is the pricing model sustainable? In addition to license fees, consider implementation (including integration and migration), training, support, storage, and feature add-ons. Don’t forget to look at the cost of utilizing AI services, too. We recommend projecting costs over at least three years to get a clear picture of the price.

5. Scalability

Will the platform grow with you? Think about asset volume, metadata complexity, user numbers, and geographic spread. If you have a particularly large collection or number of users, ask the vendors what their largest deployments are. Review whether the vendor’s roadmap aligns with your growth trajectory.

6. Security & Compliance

Does the platform meet your organization’s security and compliance requirements? Evaluate encryption, access controls, audit trails, and alignment with standards like GDPR or SOC 2. Consider both technical and policy aspects.

7. Ecosystem Fit

How well does the platform integrate with your current systems? Assess APIs, connectors, plugin availability, and the vendor’s experience with relevant third-party tools. Custom integration can quickly become a significant area of cost and complexity, so look for vendors that plug-in to your ecosystem easily.

8. Social Proof

Have similar organizations (in industry, size, scale, complexity) adopted this platform successfully? Are they growing with it over time? Review case studies, references, and testimonials. Speak directly with current customers to learn about the vendor’s strengths and limitations.

9. Trust

Does the vendor seem like a reliable long-term partner? Look at financial stability, delivery track record, and support reputation. Review SLAs, support channels, and upgrade policies. You’ll get great insights when you speak to other customers.

10. Exit Path

If your needs change, can you move on easily? Ask vendors how they support full export of assets, metadata, vocabularies, and user data in open formats. Understand the terms and costs of a potential exit.

Assign Weights and Score Objectively

Not all criteria carry the same weight. A nonprofit with limited IT support may prioritize feasibility and security, while a global brand may focus on integration and scalability. Assign weights to reflect your priorities, then score each option accordingly.

Final DAM evaluation using weighted scoring

Include a cross-functional team in the process to reflect diverse perspectives and build alignment. Document your evaluation so you can refer back to it as needed.

Avoid Common Final-Decision Pitfalls

Even with a strong evaluation process, watch out for these missteps:

- Letting brand recognition or peer adoption sway your decision

- Letting cost outweigh actual needs

- Underestimating implementation, integration, and migration effort

- Failing to thoroughly vet vendor support and services

Get Internal Buy-In and Document the Decision

Before finalizing, make sure all key stakeholders are aligned. Review the decision rationale with leadership, legal, procurement, and IT to surface any final concerns. And as a reminder, don’t forget to talk to your chosen vendor’s current customers (and not just the ones they suggest you talk to!)

Document your decision, including priorities and tradeoffs. This record will be valuable during implementation and future reviews.

Final Thoughts

Selecting a DAM system is more than a software purchase. It’s a strategic decision that will shape how your organization manages content for years. Use comprehensive evaluation criteria and a collaborative process to choose with confidence.

When implementation begins, you’ll be glad you did.

Digital Asset Management Demos and Proof of Concepts

27 August 2025

Digital asset management demos and POCs are where things get real. A demo is a live, guided walkthrough of your specific usage scenarios—ideally using your actual assets. A proof of concept (POC) goes further, giving your team hands-on access to test how the system performs with real workflows. Together, they offer a grounded, honest look at whether a system fits, not just how it looks in a sales deck.

A structured, goal-driven approach to managing these activities is the best way to move from feature lists to informed decisions.

Before the Demo: Set Your Foundation

Start by defining what matters most to your organization. Common areas to evaluate in a DAM system include:

- Workflow automation

- Metadata structure and taxonomy

- Permissions and user roles

- Search and discovery

- Upload and download processes

- User interface and experience (UI/UX)

- Integrations with other systems (e.g., CMS, PIM, MAM)

Also consider what makes your organization unique. Do you manage large volumes of high-resolution images, video, or audio (rich media)? Do you need to preserve or migrate older, inconsistent, or incomplete metadata (often referred to as legacy metadata)? These factors should inform the usage scenarios you ask vendors to demonstrate or support during a proof of concept (POC).

If you haven’t created usage scenarios yet, now’s the time. A usage scenario is a short, structured description of a key task a user needs to perform in the system. Each should include:

- A clear title

- The goal or objective

- The user role

- A brief narrative of the scenario

- Success criteria

Aim for 6 to 8 scenarios that reflect your core needs across different user types. A focused set like this keeps digital asset management demos and POCs grounded in what really matters to your team and ensures a more meaningful evaluation.

Preparing for the Demo

Give vendors a chance to show how their system handles your real-world needs. Ask them to walk through 4–5 key tasks your users need to perform in a two-hour demo session.

About two weeks before the demo, send each vendor a small sample of your actual content—around 25 assets in a mix of file types and sizes—along with a simple spreadsheet describing those files (titles, descriptions, dates, etc.). If you work with items made up of multiple files (like a book with individual page scans), include one or two of those as well.

The goal is to see how the system performs with your materials—not polished demo content—so you can better understand how it might work for your team.

Digital Asset Management Demo Participation and Structure

Invite a diverse group:

- Core users

- Edge users with atypical needs

- Technical staff

- Decision-makers

Suggested agenda:

- 30 minutes – Slide-based intro and vendor context

- 60 minutes – Live walkthrough of your usage scenarios

- 30 minutes – Open Q&A

Distribute a feedback form before the demo so your teams can rate the system and each usage scenario in real time. Collect quantitative scores (e.g., “On a scale of 1–5, how well did the system support this scenario?”) to make it easier to compare vendors side by side. Include a few qualitative prompts as well, such as “What surprised you?” or “What did you like or find confusing?” Keep the form short and focused—if it’s too long, people won’t fill it out.

Running the POC

Once you’ve identified a finalist, it’s time for hands-on testing. A two-week POC is ideal—short enough to keep momentum, long enough to explore.

Set expectations upfront. Testers must dedicate focused time. The POC isn’t a background task. If people delay or casually click around, you won’t get meaningful results.

Check with the vendor about potential POC costs. Some vendors charge if their team invests heavily and you don’t purchase. Ask early.

Prepare for a successful POC:

- Give vendors ~3 weeks to configure the system with your content and workflows. Share usage scenarios and access needs early.

- Assign clear roles, for example:

- End Users – Test search, discovery, and downloads

- Creators – Test uploads, tagging, and editing metadata

- Admins – Test permissions, structure, workflows, and configuration

- Create a task-based script aligned with your usage scenarios. Ask testers to log their experience, pain points, and surprises.

- Schedule three vendor touchpoints:

- Kickoff (60 min): Introduce the vendor, ensure everyone has access, clarify roles, and walk through the POC goals and script.

- Midpoint Check-in (30 min): Surface blockers or confusion while there’s still time to fix them. Encourage open questions: “How do I…?” or “Why isn’t this working?”

- Wrap-up (30 min): Review what worked and what didn’t. Ask the vendor to walk through anything missed. Preview post-purchase support and onboarding to help gauge confidence in next steps.

Reminder: This is not a sandbox. Stick to the script, test with intention, and focus on how the system performs in a real working scenario.

Decision Making

Pull your team together while the experience is still fresh.

Start with the structured feedback:

- Compare rubric scores across categories like usability, metadata, permissions, and admin tools.

- Look for patterns or outliers: did some roles struggle more than others?

- Discuss gaps, friction points, and what’s non-negotiable.

If your group is large, collect final thoughts via a form and summarize for review.

Document your decision—not just which system you chose, but why. Connect it to your business goals, priorities, and user needs. This not only strengthens your recommendation, but also provides valuable context for onboarding new users and teams. When people understand the reasons behind the choice, they’re more likely to engage with the system and use it effectively. It also gives you a foundation for measuring success after launch.

Final Thoughts

Digital asset management demos and POCs don’t just validate vendor claims, they clarify your priorities, surface assumptions, and test how ready your team is for change. They help you figure out not just if a system works, but how it works for you.

A well-run process builds alignment, fosters engagement, and reduces risk by exposing critical gaps early. Most importantly, it sets the stage for a smoother implementation.

When you choose a system based on real tasks, real users, and real feedback, you’re not just buying software. You’re investing with confidence.

Conducting Market Research and Shortlisting Digital Asset Management Vendors

27 August 2025

Choosing a Digital Asset Management (DAM) system is one of the most critical decisions an organization can make for managing digital content. But diving into the DAM market without guidance can be overwhelming. Dozens of vendors offer similar feature sets, and without a clear plan, it’s easy to get lost in marketing jargon or swayed by a sleek demo that doesn’t reflect your real-world needs.

This process isn’t just about picking a product. It’s about starting a long-term relationship with a vendor who will support your team, evolve with your workflows, and play a role in your digital strategy. That’s why thoughtful market research and intentional shortlisting are essential.

Begin with Requirements, Not Features

Effective vendor research starts with clarity about your needs. Before browsing solutions, define what your organization actually requires from a DAM platform. Consider:

- Who your primary users are and what they need to do with assets

- What types of assets you manage (images, video, audio, documents)

- Metadata standards and requirements

- Integration needs (CMS, PLM, PIM, creative tools, cloud storage, preservation)

- Permission models and access control

- Reporting, analytics, and training needs

List “must-have” and “nice-to-have” features, then use that as your rubric. This helps you stay focused on what matters and avoid shiny features that don’t advance your goals.

Navigating the Digital Asset Management Marketplace

A web search is a fine place to start, but it’s not enough. Vendor websites offer a polished view, but few provide meaningful detail about true differentiators, limitations, or ideal usage scenarios.

Sites like G2, Trustpilot, and Capterra offer user-generated reviews and side-by-side comparisons, which can be helpful for spotting trends or potential red flags. That said, be aware that many listings are paid placements, and reviews often lean toward the extremes—either very positive or very negative. Also, many of the tools listed on these sites aren’t actually full-featured DAM systems. Some, like Canva or Airtable, offer DAM-like features but may not meet the broader needs of your organization. This can make it tricky to distinguish between tools that support part of the workflow and those that can truly serve as a centralized DAM solution.

For deeper and more balanced insight, explore:

- DAM News – Offers industry-specific news, vendor updates, and interviews with practitioners.

- CMSWire – Covers a range of digital workplace topics, including strong, up-to-date content on DAM.

- LinkedIn – A powerful resource where DAM professionals share real-world insights, lessons learned, and vendor experiences. Connect with industry peers who have already implemented a DAM and ask for honest feedback and recommendations.

Research Firms & Case Studies

- Reports from Gartner, Forrester, and Real Story Group provide in-depth vendor evaluations and market analysis. (You can typically find these linked from vendor websites.)

- Seek out case studies from vendor websites to understand how specific solutions perform in real-world contexts.

Industry Events

Consider attending a Henry Stewart DAM Conference, which gathers DAM professionals and vendors for learning and networking. These take place annually in:

- London (June)

- New York City (October)

- Sydney (November)

- Los Angeles (March)

These events offer an opportunity to demo different systems and meet digital asset management vendors in person, expert panels, and the opportunity to hear directly from other organizations about their selection and implementation journeys.

Learn from Peers, with Context

Colleagues can be a great source of insight. Ask what systems they use, what worked well or poorly, and what they’d do differently. These conversations reveal how vendors behave during implementation and long-term support.

But keep in mind: a DAM that works well for your pal over at their organization may not be right for you. Your users, workflows, and digital strategy are unique. A negative experience elsewhere might reflect poor alignment rather than a flawed system. Treat peer feedback as helpful context, not universal truth.

Consult the Experts

If you lack time or in-house expertise, consider hiring a DAM consultant. Specialists know the landscape, can translate your needs into actionable requirements, and can help you run a disciplined selection process. They can also facilitate internal conversations neutrally to surface user needs and pain points, ensuring decisions are informed by real requirements and aligned with strategic goals.

Digging into DAM Differentiators

Most DAMs claim to offer robust features—AI, metadata support, flexible permissions, and more. These terms sound impressive, but they rarely reveal how the system actually works in practice. Real differentiators are found in the details across all functionality areas.

For example:

- “AI” alone isn’t helpful. One platform might offer basic auto-tagging, another facial recognition, or full generative AI descriptions and AI-driven workflows tied to metadata.

- “Controlled vocabularies” are standard. A system with the ability to support complex taxonomies, multilingual thesauri, or ontology integration might stand out if this is what your organization need.

- “Permissions” are expected. Granular controls, field-level restrictions, and automated rights management are worth noting.

Ask vendors for documentation that shows actual configuration options, not just marketing overviews. In demos, go beyond checklists. Ask how it performs at scale, supports your asset types, and adapts to real-world workflows. If you don’t push, vendors may not volunteer specifics.

Engage Digital Asset Management Vendors with Purpose

Once you reach out to digital asset management vendors, you’re signaling interest. Sales reps will follow up. That’s expected. Many will work hard to win your business, and that can be a good thing. But this isn’t just a sales transaction. If you choose their system, you’ll likely be working closely with that company for years.

Pay attention to how vendors engage with you. Do they ask thoughtful questions about your needs? Offer strategic guidance? Or are they focused only on closing the deal? You want a partner, not just a product.

Ask tough, specific questions. Request use-case examples. Involve your users early so they can determine if the system fits their actual workflows.

Early demos can help you understand layout and navigation. But once you’re seriously considering a system, ask for tailored demonstrations using your scenarios and assets. This helps you evaluate both product fit and vendor fit—their responsiveness, flexibility, and support philosophy. And if you really want to get under the hood, consider doing a proof of concept with your top 1-2 finalist vendors.

Building the Shortlist

A shortlist should include only those digital asset management vendors who align with your requirements, fall within your budget, and seem like a cultural fit. Aim for five to six vendors for your Request for Information (RFI) or Request for Proposal (RFP).

After reviewing the vendors’ responses, narrow the list to two or three finalists. Invite them for detailed demos, reference calls, and technical Q&A. Note that at this point, you’re evaluating the partnership as much as the platform.

What Makes Digital Asset Management Vendors Shortlist-Worthy

A vendor becomes shortlist-worthy not just by meeting your technical and functional requirements, but by demonstrating alignment with your organization’s broader context and strategic direction. Beyond feature fit, consider factors like company size and funding stability—these can indicate whether a vendor is likely to support and evolve their platform over the long term. Geographic location may matter for support hours, data residency, or language requirements. Longevity and client retention can signal maturity and reliability, but don’t discount newer vendors if they show strong responsiveness and innovation. Experience within your industry or with similar organizations can also be a valuable indicator of how well the vendor understands your needs and challenges. Most importantly, assess cultural and strategic fit: does the vendor listen actively, offer thoughtful insights, and seem invested in your success? A good partner should feel like an extension of your team, not just a service provider.

Final Thoughts

DAM market research is both a filtering and discovery process. It takes effort, but the payoff is a well-aligned solution that fits your organization and your future.

Stay focused on your goals. Be curious, but critical. Ask hard questions. A solid selection process sets you up for long-term success—not just with the tool, but with the vendor team that supports it and the users who rely on it every day.

Documenting Your Digital Asset Management Criteria

1 August 2025

Choosing a Digital Asset Management (DAM) system isn’t just about comparing feature lists from vendor websites. It starts with understanding your organization’s specific digital asset management criteria: what assets you manage, how your teams work, what’s not working, and where you’re headed. To make good decisions, you need clear documentation that captures those needs in a reusable, structured format.

This article offers practical guidance to help you build that foundation, with examples and templates you can reuse throughout your planning process, including RFP development, vendor evaluations, and internal alignment.

1. Start with a Centralized, Collaborative Document

Use a collaborative tool like Google Sheets, SharePoint, Excel, or AirTable to keep your documentation organized and visible to stakeholders. Create tabs that reflect the key areas in this article (e.g., Stakeholders, Usage Scenarios, Assets, Metadata), and structure your notes in a clear, sortable format. This makes it easier to spot patterns, prioritize shared needs, and track where each requirement came from. Your spreadsheet becomes a central source of truth for drafting your RFP, comparing vendors, and aligning internally.

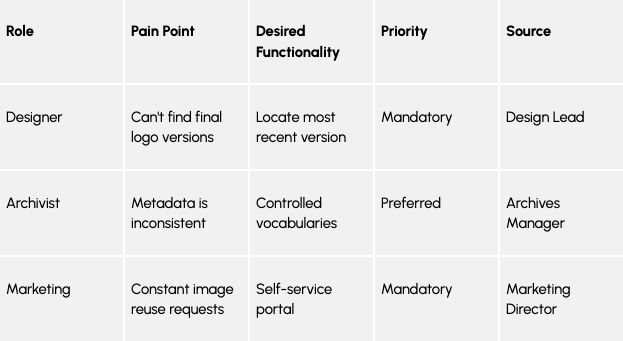

2. Interview Stakeholders and Track Themes

Record short interviews (with permission) with stakeholders in marketing, creative, archives, IT, legal, and other teams that work with digital assets. Focus on what tools they use, where processes break down, and what they wish were easier.

Skip surveys. Interviews offer deeper insight into workflows, pain points, and expectations, and help you capture the language people actually use. These conversations will ground your future steps, ensuring the DAM supports real-world needs.

Tip: “Role” refers to the type of user experiencing the need (e.g., Designer, Archivist), while “Source” refers to the specific person or department who shared that insight during interviews (e.g., Design Lead, Archives Manager). This helps you see how broadly a need applies and trace it back to the original stakeholder if you need more context later.

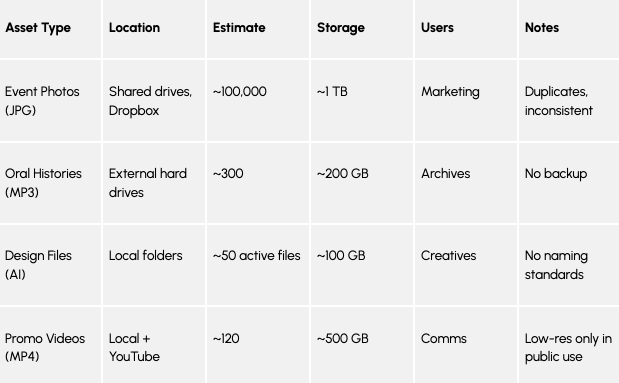

3. Inventory Your Digital Assets (Rough Counts Are Fine)

You don’t need a full audit, just a rough idea of what you have, where it is, and who uses it. Include file types, volume estimates, and storage sizes:

This information is essential for planning migration and estimating storage needs, and vendors will need a summarized version to provide accurate costs in their proposals.

4. Look for Metadata (Even If You Don’t Call It That)

Even if you’re not using a formal metadata system yet, your team is probably tracking important information about your assets, like who created them, what they’re about, or how they can be used. That’s metadata.

Start by identifying what kind of information you already track and where it lives. It could be:

- In filenames or folder names

- In a spreadsheet

- Stored inside the file itself (like photo properties and technical information about the file)

You might also hear terms like:

- Metadata schema: This just means a consistent set of fields used to describe your assets, for example, “Photographer,” “Date Taken,” or “Usage Rights.” If you’re not using one yet, that’s okay. Start by listing what you are tracking.

- Embedded metadata: This is metadata that’s saved inside the file itself. For example, a photo might include the date it was taken, the camera model, or GPS location.

You might be tracking more metadata than you realize. Look around, especially in shared drives, naming patterns, or that old spreadsheet someone still updates manually. This will help you decide what metadata to keep as-is, what to standardize, and what metadata to capture automatically (with AI) once your DAM is in place.

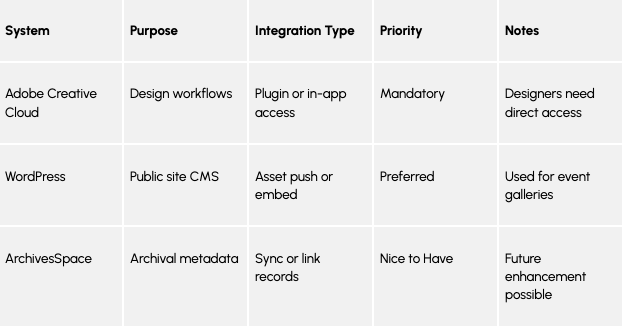

5. Document Integration Needs Across Systems

Most DAM systems won’t stand alone. They often need to connect to tools your team already uses. These could include your website CMS, creative tools from Adobe, or archives and records systems.

Think about what other tools or systems it should work with.

Start by making a list of all the software your team already uses—like design programs, content management systems, cloud storage, or social media tools. Then, for each one, ask:

“What do we need the DAM to do with this system?”

For example:

- Your designers might want to pull images straight from the DAM while working in Adobe Creative Cloud, without switching between tools.

- Your marketing team might need the DAM to automatically send approved images to your website or social media platform.

Making this list now will help you choose a digital asset management (DAM) system that plays nicely with the rest of your tech setup—and saves your team time down the line.

Even if you’re not sure how the integration will work yet, noting your needs now gives vendors and IT something concrete to work with later.

6. Capture Technical Requirements Up Front

Before you choose a digital asset management system, it’s important to document any technical expectations your IT team or organization has. These might include how users will log in, where the system is hosted, or what kind of security and accessibility standards it needs to meet.

Start with questions like:

- Does your organization require Single Sign-On (SSO)?

- Do you prefer a cloud-based system or one hosted internally?

- Are there file size limits you need to support?

- Do you have accessibility or compliance requirements?

No need for a technical spec. Just capture the basics to share with vendors.

Final Thoughts

Take your time with documenting your digital asset management needs. It can be tempting to jump straight into vendor conversations, but a clear, well-documented foundation will save time, reduce confusion, and support better decisions later on.

And don’t try to do it alone. Involve the people who will use the DAM every day. Their input will save you from surprises later, and probably make the system better for everyone.

Appendix A. DAM Selection Planning Checklist

Once you’ve done some of this early prework, like interviewing stakeholders and identifying your assets, you can move on to this checklist. It’s comprehensive and may feel overwhelming at first, but you don’t have to tackle it all at once. Take it step by step. Collaborate with your main stakeholders. Check in with IT. Use this list to structure your planning, shape your RFP, and guide vendor conversations.

The good news is, if you’ve done the work above, this list will feel much more manageable and actionable.

Strategic Foundation

- What purpose will your DAM system serve, and what problems is it meant to solve?

- What does success look like, and how will you measure it?

- What does Phase 1 (Minimum Viable Product) look like?

Users & Stakeholders

- Who are your key users and stakeholders?

- Have you conducted recorded interviews with them?

- What pain points and needs did they share?

- Have you tracked themes across roles and prioritized them?

- Who will administer the DAM system?

Usage Scenarios & Requirements

- Have you written future-focused usage scenarios for core roles?

- Have you written user stories that describe desired functionality?

- Are your requirements categorized as Mandatory / Preferred / Nice to Have?

- Are sources (departments, individuals) attributed to each requirement?

Assets & Storage

- What types of digital assets do you manage? (e.g., images, videos, audio, 3D)

- Where are they stored now? (shared drives, cloud storage, hard drives)

- What’s the estimated volume (e.g., number of files) and storage size (e.g., in TB)?

- Who uses or owns each asset type?

- Are any assets at risk (e.g., no backups, fragile storage media)?

Metadata & Organization

- What metadata do you track, even informally (e.g., in file names or spreadsheets)?

- Where does that metadata live (e.g., embedded, folder structures, Excel)?

- Do you have consistent file naming conventions?

- Do you use any controlled vocabularies or taxonomies?

Workflow & Lifecycle

- Who creates, reviews, approves, and publishes digital assets?

- What do your current workflows look like, and where are the pain points?

- Do you distinguish between Work in Progress (WIP) and Final assets?

- How are assets currently tagged and ingested?

- Who will manage migration and tagging into the new DAM?

Digital Preservation

- Do any assets need long-term preservation beyond active use?

- Are there embargoing, archiving, or retention policy requirements?

- Will the DAM integrate with a preservation system or strategy?

Licensing & Rights

- Are you currently tracking usage rights and license information?

- Do you know which channels, regions, and formats assets are approved for?

- Are any licenses expired, missing, or uncertain?

- How will user roles, permissions, and security be defined in the DAM?

UX / UI

- What should the user experience be like for search, upload, and browsing?

- Do you need features like thumbnails, preview players, or 3D viewers?

- Do you need multilingual interface support?

- How will different user types (e.g., casual vs. power users) interact with the system?

Integration Requirements

- What systems should the DAM integrate with (e.g., CMS, PIM, Adobe CC)?

- What kind of integrations do you need (e.g., push/pull assets, metadata sync)?

- Are any integrations vendor-supported or likely to require customization?

- Which integrations are Mandatory, Preferred, or Nice to Have?

Technical Requirements

- Do you require SaaS (cloud-based) or on-premise deployment?

- Is SSO (Single Sign-On) required (e.g., via SAML or OAuth2)?

- Are there preferred storage providers or data residency requirements?

- What is the max file size or upload threshold?

- Do you need accessibility compliance (e.g., WCAG 2.1 AA)?

- Will the DAM need to support public delivery of assets with secure access?

Timeline & Budget

- What is your ideal timeline for selection, contracting, and go-live?

- What is your estimated first-year cost?

- What is your projected ongoing cost (e.g., storage, licensing, support)?

- Will implementation be phased or rolled out all at once?

A DAMn Good Investment

24 June 2025

When the going gets tough, the tough get investing.

With economic instability, the pressure is on leaders to tighten belts yet remain top of mind for target markets. In 2025, the global economy has been wildly unpredictable with tariffs, layoffs, and consumer confidence unstable. And, one of the biggest mistakes I see business leaders make during times of uncertainty is cutting their marketing and advertising budgets altogether. To unlock the full potential of a company’s data for informed decision-making, it is essential that data be accurately recorded, securely stored, and properly analyzed. This becomes especially critical during economic downturns, when financial scrutiny intensifies and every margin matters. Data presented to prospects and existing customers must be precise to ensure that services and differentiators are clearly and correctly communicated. Internally, the accuracy of data shared with executives and analysts can directly influence client retention, strategic direction, and budget planning.

This is also a matter of operational efficiency. Even with effective employee training, the benefits can only be realized if teams are working from a consistent and reliable source of truth … DAM. Establishing this foundation is an investment that relies more on strategic time allocation than significant capital expenditure. To position itself for future growth, a company cannot afford to be complacent when evaluating potential technology investments. In a fast-moving digital landscape, organizations that delay improvements during slow periods risk falling behind. In contrast, companies that make deliberate investments—whether through new systems or by dedicating employee time to development and training—will be better prepared to seize emerging opportunities and showcase their competitive advantages as conditions improve.

This is a good time to invest in DAM.

Change is a Good Investment

Change is as present as it is pervasive. It is good to recognize, acknowledge and accept that change is happening in business, and to learn not only what that means for you and your team, but to be ready for those new opportunities. So, why do we change?

- We change to advance forward.

- We change to make ourselves stronger.

- We change to adapt to new situations.

Without change, there would be no improvements. If business is about growing, expanding and making things better for your customers, then what changes are you making? As many of us begin to see future recovery, I too look to the horizon and know that better days are ahead for us all. Whether you’re undertaking an improvement, an upgrade or modernization, whatever you call it, any such effort is holistic by design, encompassing all aspects of business. Many businesses have taken this time to focus on improving all aspects of their business that affect people, process, and technology. This is about good and positive access to information from many systems to not hinder but enable our work. Watch for signs and respond well. Improvement for all is a good thing. In business, we always aspire for stability but need to be prepared for the opposite. This is about both insurance, and investment.

Invest in DAM

The demand to deliver successful and sustainable business outcomes with our DAM systems often collides with transitioning business models within marketing operations, creative services, IT, or the enterprise. You need to take a hard look at the marketing and business operations and technology consumption with an eye toward optimizing processes, reducing time to market for marketing materials, and improving consumer engagement and personalization with better data capture and analysis.

Time to Transform

To respond quickly to these expectations, we need DAM to work within an effective transformational business strategy that involves the enterprise. Whether you view digital transformation as technology, customer engagement, or marketing and sales, intelligent operations coordinate these efforts towards a unified goal. DAM is strengthened when working as part of an enterprise digital transformation strategy, which considers content management from multiple perspectives, including knowledge, rights and data. Using DAM effectively can deliver knowledge and measurable cost savings, deliver time to market gains, and deliver greater brand voice consistency — valuable and meaningful effects for your digital strategy foundation.

Future-Proof your Content

Consider the opportunity in effective metadata governance: do you have documented workflows for metadata maintenance? Are you future-proofing your evergreen content and data? Remember to listen to your users, to keep up to date and aware of your digital assets, and leverage good documentation, reporting, and analytics to help you learn, grow and be prepared. If you are not learning, you are not growing. If you are not measuring, then you are not questioning, and then you are truly not learning.

Conclusion

Keep the lights on. Now is the time to get smart and strategic with your money to ensure you can weather the current unpredictability and even come out ahead. Tariffs, recession fears, rising prices, and potential layoffs dominate headlines right now. As you look to the second half of the year, this might be causing you to take a close look at budget forecasts and reevaluate spending.

Play the long game. Marketing is a long-term strategy, and DAM is a cornerstone of Marketing efforts and operations. More than ever, there is a direct need for DAM to serve as a core application within the enterprise to manage these assets. The need for DAM remains strong and continues to support strategic organizational initiatives at all levels. DAM provides, more than ever, value in:

- Reducing Costs

- Generating new revenue opportunities

- Improving market or brand perception and competitiveness

- Reducing the cost of initiatives that consume DAM services

The decision to implement a DAM isn’t one to take lightly. It is a step in the right direction to gain operational and intellectual control of your digital assets. DAM is essential to growth as it is responsible for how the organization’s assets will be efficiently and effectively managed in its daily operations.

A DAMn good investment to me.

What you need to know about Media Asset Management

10 December 2024

While marketing strategies vary by company size or industry, they likely have one thing in common: a lot of content.

Every stage of the customer journey is powered by marketing content — from digital ads and social media posts to web pages and nurture emails. And if all the related workflows are going to run smoothly, all of the supporting assets need to be organized effectively.

That’s where media asset management comes in. Let’s take a look at this practice and how media asset management software can help teams achieve their content goals.

What is media asset management?

Media asset management (MAM) is the process of organizing assets for successful storage, retrieval, and distribution across the content lifecycle.

This includes any visual, audio, written, or interactive piece of content that supports a marketing goal. The list of possible marketing assets is long and can include:

- E-books

- Whitepapers

- Customer stories

- Reports and guides

- Infographics

- Webinars

- Explainer videos

- Product demos

- Podcasts

- And more!

In addition, all of these assets are produced with the help of many smaller creative elements, like images and graphics. The volume of these files grows exponentially…after all, one photoshoot alone can result in hundreds of images.

And if teams don’t have a centralized repository for their assets, finding a specific file requires a tedious search across shared drives, hard drives, and other devices — which can prove impossible without knowing the filename. Audio and video files can be particularly challenging to manage not only because they tend to be large but also because they are difficult to quickly scan. Sometimes files simply can’t be found and have to be recreated.

This content chaos all adds up to a lot of wasted time and resources…and frustration.

MAM software addresses this problem by providing teams with a single, searchable repository to store and organize all creative files — making asset retrieval a breeze.

How is media asset management software used?

While content management is important for all kinds of teams, MAM focuses on marketing assets and workflows. And the benefits of MAM are numerous — let’s explore some through common use cases.

Distributed marketing teams, one brand

It takes a village to bring a marketing strategy to life, and that village often includes numerous regional offices, remote workers, contracted agencies, and external partners. And all of these content creators and communicators need to be working towards a unified brand experience.

MAM software makes global brand management possible by providing a centralized platform to store and manage files, including brand guidelines and standards. So not only are dispersed team members working from the same playbook, but they are also using the same brand-approved assets — helping to ensure consistency across customer touchpoints.

Ease of use, powered by metadata

Marketing assets are central to workflows across an organization. For example, sales reps need current product materials for deal advancement and customer success managers use the same assets to support and educate existing customers. Their ability to work with agility depends on having these resources at their fingertips.

MAM software includes flexible metadata capabilities that power robust search tools, allowing users to locate an asset with just a few clicks — even in a repository of tens of thousands of files. Further, because MAM software offers easy-to-use versioning capabilities, users can be confident that assets are current. This efficiency accelerates workflows and fuels revenue growth.

Integrated systems and automated processes

A modern marketing technology (martech) stack includes numerous platforms to store, produce, and publish content, many of which include their own asset libraries.

By positioning a MAM system as the central source of truth for all content, teams can simplify content management and consolidate redundant tools. Powerful APIs and out-of-the-box connectors automate the flow of content from a MAM platform to other systems to ensure the same assets are used across digital destinations, without the need for manual updates across the content supply chain.

What are media asset management software options?

Organizations shopping for a MAM platform have an abundance of choices to consider. A simple search for “media asset management” on G2 — a large, online software marketplace — lists 82 products!

All of these platforms have big things in common. For example, most, if not all, are software as a service (SaaS) solutions in the cloud (versus on-premise software that is installed locally).

However, the specific features that each vendor offers can vary quite a bit. So the first step in any MAM software search is to clearly understand and outline the functionality needed for your unique workflows.

From there, you can really begin your research in earnest — or even start drafting a request for proposal (RFP).

The difference between MAM and DAM

In today’s enormous martech landscape media asset management overlaps with several other disciplines, including digital asset management (DAM).

While these two solution categories are similar (in name and practice), there are key differences.

DAM refers to the business process of storing and organizing all types of content across a company. This could mean files from the finance department, legal team, human resources, or other business units.

MAM, on the other hand, really focuses on assets that the marketing department requires, including large video and audio files.

So finding the solution that’s right for your team really starts with clarifying your functionality needs, including the types of files you want to store in your system and how you need to manage and distribute them.

Successful technology selection, with AVP

Is a MAM or DAM platform right for your organization? Further, which vendor is the best match for your marketing goals? While answering these questions can be hard, we can help.

AVP’s consultants have worked with hundreds of organizations to select the software partner that best fits their workflow and technology needs. If you’re dealing with content chaos, we’d love to hear from you.

Contact us to learn more about AVP Select — and how we can work together to achieve your content management goals, faster.

5 Warning Signs Your DAM Project is at Risk

12 September 2024

In the world of Digital Asset Management (DAM), recognizing early warning signs can mean the difference between success and failure. Chris Lacinak, founder and CEO of AVP, shares valuable insights from his extensive experience in the field. Here are the five key warning signs that indicate your DAM project may be at risk.

No Internal Champion

The absence of an internal champion can jeopardize your DAM project. This champion should possess the necessary expertise and experience to guide the initiative effectively. Pragmatically, it might sound like relying too heavily on external consultants or team members thinking they can manage without a dedicated point person. This reliance signals a potential failure in project management.

So, what does an effective internal champion look like? They need to:

- Have a solid understanding of the domain.

- Dedicate time solely to this project.

- Maintain the knowledge and context after external parties depart.

Having someone who can coordinate resources and make informed decisions is crucial for the sustainability and success of the project.

Insufficient Organizational Buy-In

Lack of organizational buy-in is another critical warning sign. If key stakeholders, especially leadership, do not understand the DAM initiative or fail to see its significance, the project is likely to struggle. This might manifest as leadership not being involved or departments feeling excluded from the process.

To foster buy-in, it’s vital to establish executive sponsorship early on. This sponsorship can come from various levels, including directors or C-level executives, who can advocate for the project and ensure it aligns with the organization’s strategic vision. Engaging with key stakeholders will help ensure they feel heard and included in the process, reducing potential pushback during implementation.

Inability to Articulate Pain Points

Another red flag is the inability to clearly articulate pain points. Statements like “we’re just a mess” or “we need a new DAM” indicate a lack of understanding of specific challenges. It’s essential to identify precise pain points to effectively address them.

Using the “Five Whys” technique can help drill down to the root of the problem. For instance, if a team is losing money, asking why repeatedly can reveal that the core issue might be difficulty in finding digital assets, leading to unnecessary recreations. This approach emphasizes that pain points are human problems, not just technological ones, and should be treated as such.

Unclear Definition of Success

Not knowing what success looks like or what the impact of solving the problem would be can lead to project derailment. If stakeholders cannot envision the outcome of a successful DAM implementation, it suggests a lack of direction and clarity.

To establish a strong business case, it’s crucial to articulate what success entails. Consider questions like:

- What will you be able to do that you couldn’t do before?

- What improvements will you see in workflows or team morale?

- How will this align with the organization’s strategic goals?

A well-defined vision of success helps secure leadership buy-in and provides a roadmap for measuring progress.

Skipping Critical Steps in the Process

Finally, wanting to skip critical steps or prematurely determining solutions can be detrimental. Statements like “we did discovery a couple of years ago” or “we just need a new DAM” indicate a lack of thoroughness in the planning process.

Discovery is essential for gathering updated information and engaging stakeholders. If stakeholders feel involved in the process, they are more likely to support the initiative and its outcomes. Rushing through this phase can lead to poor decisions and wasted resources, ultimately putting the project’s success at risk.

Conclusion

Identifying these five warning signs early on can help mitigate risks associated with your DAM project. Establishing an internal champion, ensuring organizational buy-in, articulating pain points, defining success, and taking the time to conduct thorough discovery are all critical steps toward a successful DAM implementation. By addressing these areas proactively, you can set your project up for success and avoid common pitfalls.

If you found this information helpful or have further questions, feel free to reach out to Chris Lacinak at AVP for more insights into managing your DAM projects effectively.

Transcript

Chris Lacinak: 00:00

Hey, y’all, Chris Lacinak here.

If you’re a listener on the podcast, you know me as the host of the DAM Right Podcast.

You may not know me as the Founder and CEO of digital asset management consulting firm, AVP.I founded the company back in: 2006

And I have learned what the early indicators are that are likely to make a project successful or a failure.

And I’m gonna share with you today five warning signs that your project is at risk.

So let’s jump in.

Number one, there is no internal champion to see things through, or there’s an over-reliance on external parties.

Now, what’s that sound like pragmatically?

That sounds like, “that’s why we’re hiring a consultant”, or “between the three of us, I think we should be able to stay on top of things.”

You might think it’s funny that myself as a consultant is telling you that you should not have an over-reliance on external parties, but the truth of the matter is, is that if you are over-reliant on us, and you are dependent on us, we have failed to do our job.Chris Lacinak: 01:06

That is a sign of failure.

But let’s talk about the champion.

What’s the champion look like?

Well, first and foremost, it’s someone who has the right expertise and experience.

We wanna set this person up for success.

They need to have an understanding of the domain.

They don’t have to be the most expert person, but they need to understand, they need to be conversant, they need to understand the players, the parts, how things work.

They need to be knowledgeable enough that they’re able to do the job.

Second, they need to have the time.

This can’t be, you know, one of ten things that this person is doing, part of their job.

It needs to be dedicated.

And it can’t be something that’s shared across three, four, five people.

That’s not gonna work either.

Things will slip through the cracks.

Now, why is this important?

Well, it’s important because it mitigates the reliance on external parties, as I’ve already said.

But what’s the other significance?

The other significance is that once the consultant leaves, or once the main project team is done doing what they’re doing, whether that’s an internal project team or external project team, this person is gonna be the point person that is going to maintain the knowledge, the history, the context of the project.Chris Lacinak: 02:14

They’re gonna have an understanding of what the strategy, what the roadmap is, what the plan is, and they’re gonna help execute that.

They’re gonna be the point person for coordinating the various resources, the people.

And, you know, it’s gonna depend what this position looks like as to what authority they have, what budget control they have, things like that, about exactly what it looks like.

But more or less, this person is either gonna be, you know, the main point of recommendations and influence, or they might even be the budget holder and actually be making the calls and decisions.

But one way or another, you need somebody that is gonna see this through, that’s internal to your organization in order for it to be sustainable and for it to succeed.

Number two, not enough organizational buy-in or poor socialization.

What’s that sound like in practice?

Well, it might sound like “leadership doesn’t understand, they just don’t get it.”

Or “there’s issues with that department that we don’t need to go into here, but we don’t need to include them.

They’ll have to fall into place once we do this.”

Or “we haven’t talked with folks about this yet, but we know it’s a problem that needs to be fixed.

It’s obvious.”Chris Lacinak: 03:14

Those are all signs that there’s poor socialization and that you haven’t gotten the appropriate buy-in from the organizational key stakeholders.

Now, who are the key stakeholders?

Well, let’s start with executive sponsorship.

It’s critically important that there’s an executive sponsor.

Now, executive can mean a number of things.

It could be director level, it could be C-level.

Essentially, it’s someone who is making decisions, is a key part of fulfilling strategy for the organization, the department, the business unit, has budget and is making budget calls.

So why is this important and how do you respond to this?

Well, it’s important because executive sponsorship is looking out for the vision, the strategy, the mission, and the budget of the organizational unit.Chris Lacinak: 03:59

You can’t be sneaky and successfully slip a DAM into an organization, right?

There’s no such thing as a contraband dam.

It’s not like that bag of chips you sneak into the grocery cart when your significant other is looking the other way.

It’s an operation, it’s a program.

It requires executive sponsorship.

It requires budget.

It requires a tie-in into the strategy, the vision, and the mission.

It’s not a bag of chips.

It’s all that and a bag of chips.

Who are the other key stakeholders?

Well, your key stakeholders are gonna be the other people that are either contributors, users, or supporters of the DAM in some way.

‘Cause it is an operation.

A dam has implications to workflows, to policies, to behaviors.

It touches so many different parts of the organization.

So it’s critically important that your key stakeholders are included as early on in the process so that they feel heard, they feel included, they feel represented.

And when it’s time to roll out that DAM, you don’t have people going and looking backwards, right?Chris Lacinak: 04:57

Everybody has an understanding of where you are, why you’ve arrived there, and how you’re moving forward.

And even if they don’t agree, they understand and they’re on board.

And you want concerns and objections.