Article

AMPlifying Digital Assets: The Journey of the Audiovisual Metadata Platform

11 July 2024

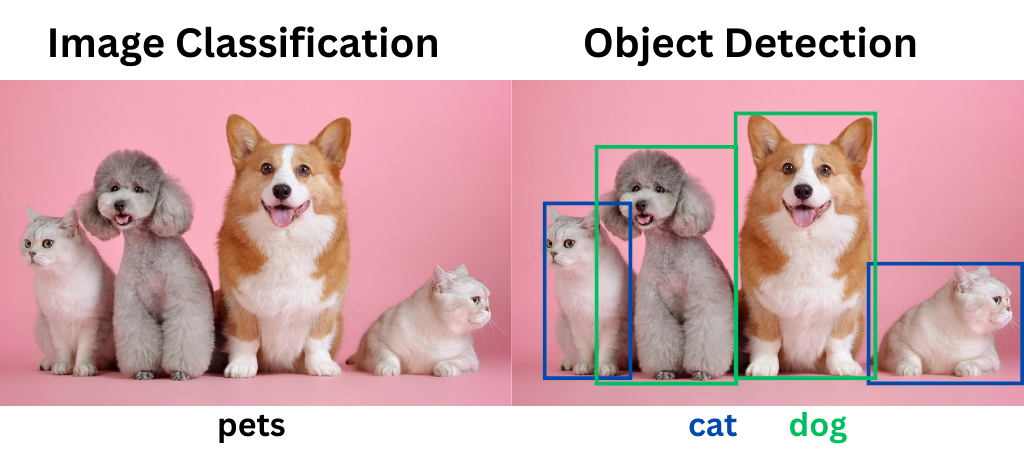

The digital landscape has transformed dramatically in the last decade. AI has reemerged as a powerful tool for asset description. This evolution has enabled previously hidden assets to be discovered and utilized. However, AI tools have often operated in isolation, limiting their full potential. This blog discusses the Audiovisual Metadata Platform (AMP) at Indiana University, a groundbreaking project creating meaningful metadata for digital assets.

Context and Genesis of AMP

Many organizations are digitizing their audiovisual collections. This highlighted the need for a unified platform. Indiana University, with Mellon Foundation funding, initiated the AMP project. Their goal was to help describe over 500,000 hours of audiovisual content and support other organizations facing similar challenges.

The Need for Metadata

Digitization efforts produce petabytes of digital files. Effective metadata is essential to make these collections accessible. AMP addresses this need by integrating AI tools and human expertise for efficient metadata generation.

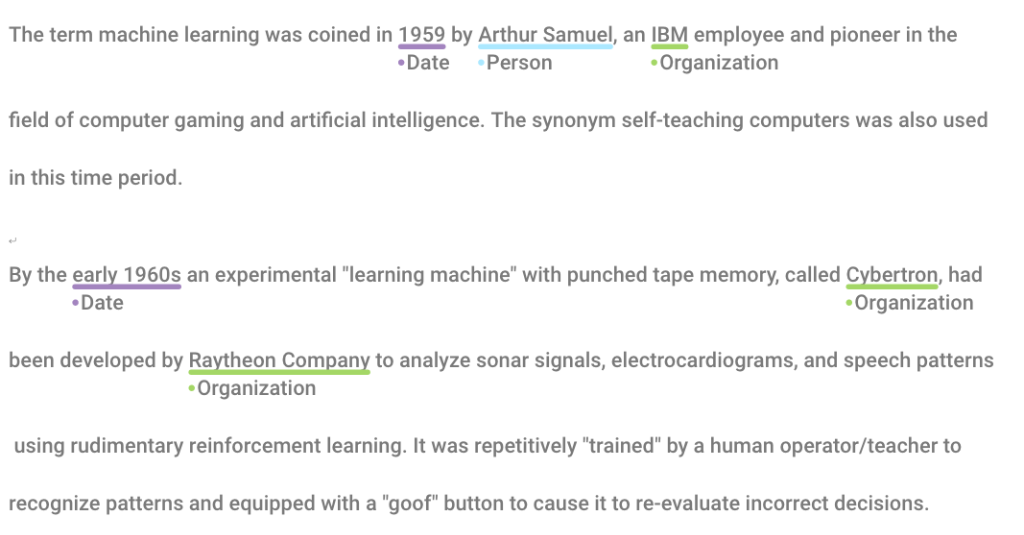

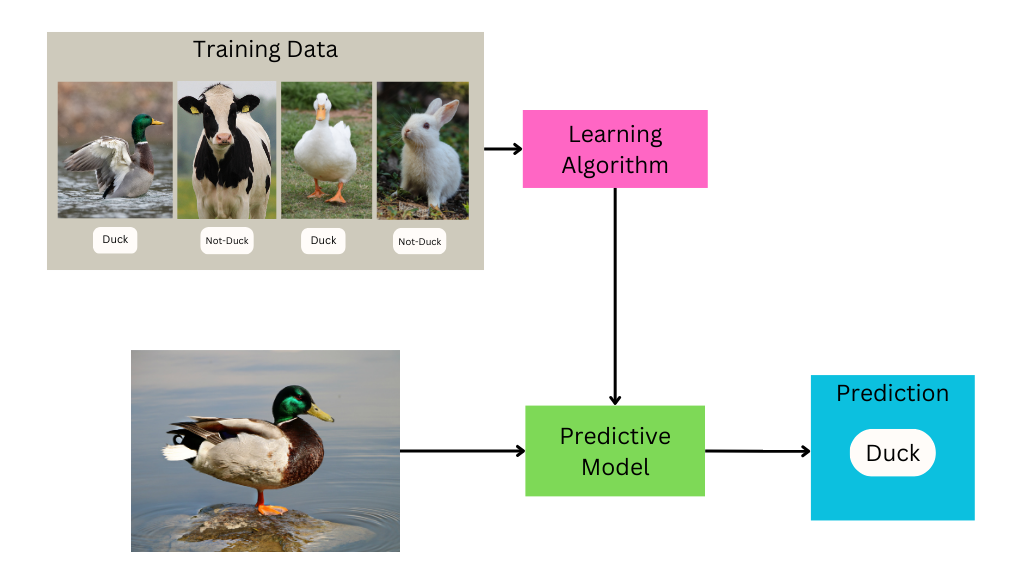

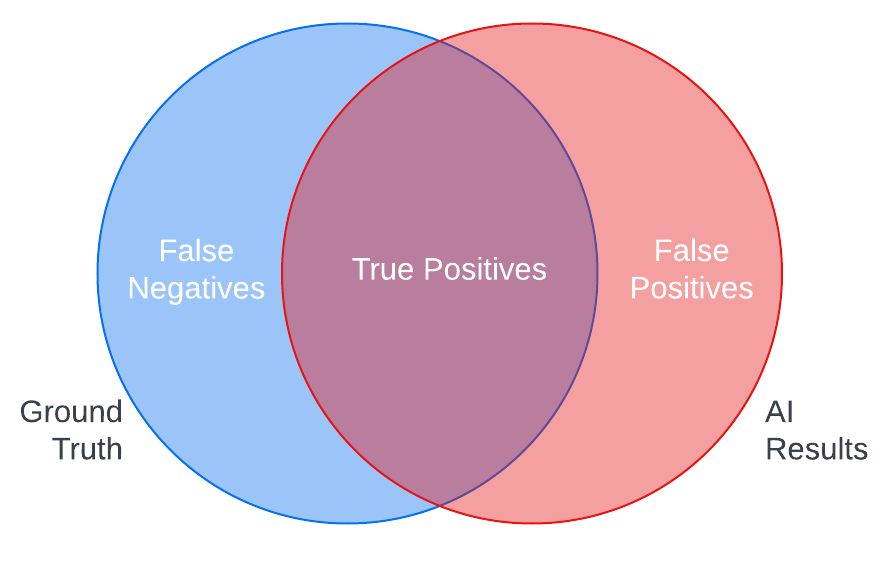

The Role of AI in Metadata Creation

AI helps automate metadata generation, but integrating various AI tools into one workflow has been challenging. AMP was designed to combine these tools, incorporating human input for more accurate results.

Building Custom Workflows

AMP allows collection managers to build workflows combining automation and human review. This flexibility suits different types of collections, such as music, oral histories, or ethnographic content. Managers can tailor workflows to their collection’s needs.

The User Experience with AMP

Collection managers are the main users of AMP. They often face complex workflows. AMP simplifies this with an intuitive interface, making it easier to manage audiovisual collections.

Integrating Human Input

Human input remains essential in AI-driven workflows. AMP ensures that human expertise refines the metadata generated by AI tools, preventing AI from replacing traditional cataloging roles.

Ethical Considerations in AI

Ethical considerations are crucial in AI projects. AMP addresses issues like privacy and bias, ensuring responsible AI implementation in cultural heritage contexts.

Privacy Concerns

Archival collections often contain sensitive materials. AMP has privacy measures, especially for AI tools used in facial recognition. Collection managers control these tools, ensuring ethical responsibility.

Collaboration and Community Engagement

AMP is designed to be a collaborative platform. It aims to engage with institutions, sharing tools and insights for audiovisual metadata generation.

Partnerships and Testing

AMP has partnered with various institutions to test its functionalities. These collaborations provided valuable feedback, refining the platform to meet diverse user needs.

Future Directions for AMP

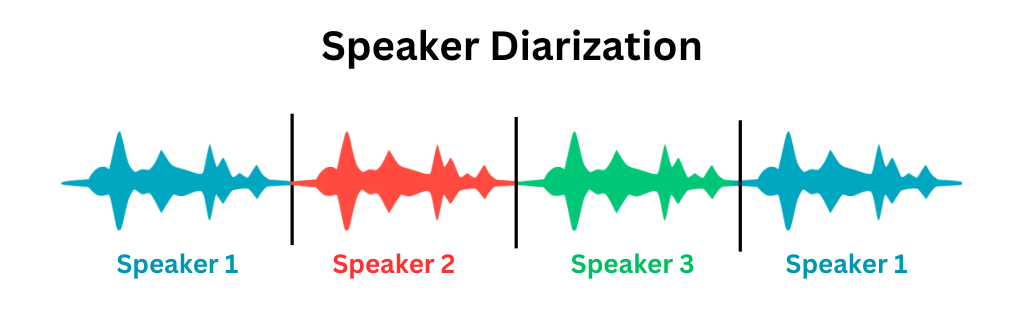

AMP’s journey continues as technology evolves. New AI tools like Whisper for speech-to-text transcription are being integrated.

Expanding Capabilities

AMP aims to enhance its metadata generation process with more functionalities. It seeks to improve existing workflows and incorporate advanced AI models for accuracy.

Conclusion

AMP represents a significant advancement in audiovisual metadata generation. By integrating AI and human expertise, it offers efficient management of digital assets. As it evolves, AMP will continue providing value to cultural heritage institutions.

Resources and Further Reading

- AMP Project Site

- Mellon Foundation

- BBC Transcript Editor

- INA Speech Segmenter

- Galaxy Project

- Kaldi ASR

The Importance of Broadcast Archives: Insights from Brecht Declercq

27 June 2024

Broadcast archives are an invaluable resource for understanding the cultural, social, and political history of the 20th and early 21st centuries. In this blog post, we will explore the significance of these archives, the challenges they face, and the future of broadcast operations as we transition to a digital age.

Understanding Broadcast Archives

Imagine you are a future archaeologist trying to comprehend the lives of people from the early 1900s to the early 2000s. What would be the most robust source of information? While institutions like the Library of Congress and various landfills have their merits, broadcast collections produced by radio and television broadcasters are arguably the most comprehensive source. These collections hold stories that document the formation of nations, cultural shifts, and significant political events.

The Unique Role of Broadcasters

Broadcasting entities have amassed vast collections over the years, capturing the essence of their respective societies. Through a mix of entertainment, news, and cultural programming, they have created a historical record that includes comedy, drama, and sports. These archives are not just a collection of shows; they are a reflection of the times, offering insights into the prevailing attitudes and events of various eras.

Meet Brecht Declercq

Brecht Declercq is a leading expert in the field of broadcast archives and has served as the President of FIAT/IFTA, the International Federation of Television Archives. His extensive experience in the field has equipped him with invaluable insights into the challenges and opportunities facing broadcast archives today.

The Role of FIAT/IFTA

FIAT/IFTA is the world’s leading professional association for those engaged in the preservation and exploitation of broadcast archives. The organization focuses on creating and exchanging expert knowledge while promoting awareness of future media archiving. With membership spanning public broadcasters, commercial entities, and audiovisual archives, FIAT/IFTA aims to build a global community dedicated to preserving audiovisual heritage.

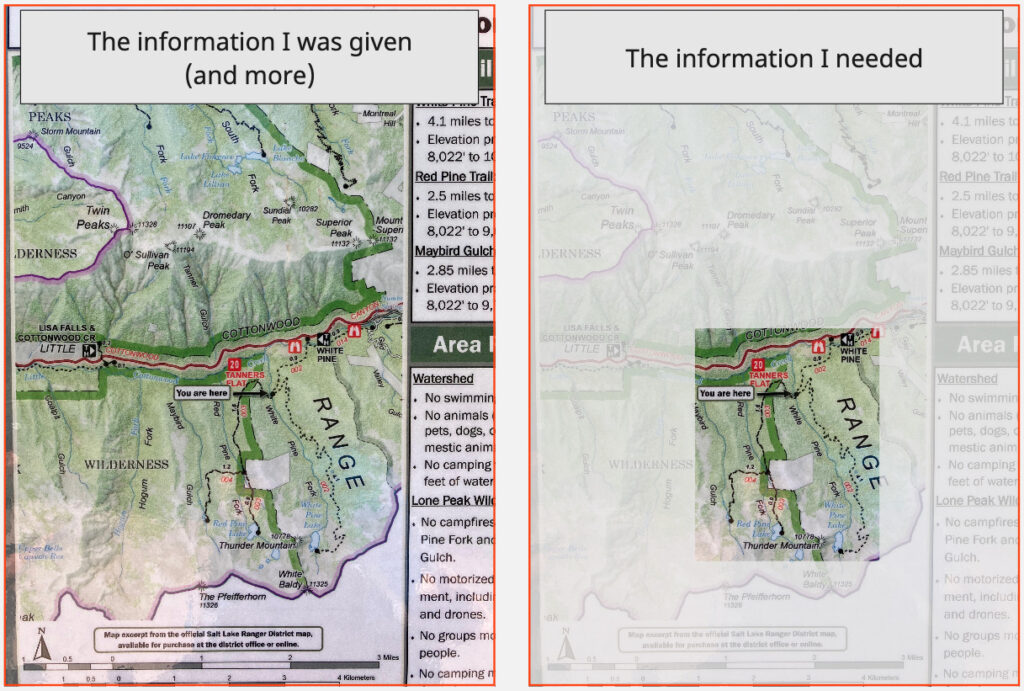

Surveying the Landscape

One of the organization’s key initiatives is conducting surveys to gauge the state of broadcast archives worldwide. These surveys provide crucial insights into the evolution of archiving practices and highlight the challenges faced by institutions across different regions. For instance, the “Where Are You on the Timeline?” survey allows members to assess their progress in digitization and other archival practices.

The State of Broadcast Archives Worldwide

While some regions enjoy advanced archival practices, others struggle with significant challenges. In wealthier countries, many broadcasters have completed digitization efforts, preserving their audiovisual heritage. However, in less affluent regions, many archives remain in a state of disrepair, risking the loss of critical historical documents.

The Impact of Economic Factors

The financial health of a country plays a significant role in the preservation of its broadcast archives. In economically disadvantaged areas, the degradation and obsolescence of audiovisual carriers are prevalent. This leads to a situation where important historical records may be lost forever, resulting in a gap in our understanding of history.

AI and the Future of Archiving

The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) has introduced new possibilities for managing broadcast archives. AI can enhance the efficiency of cataloging and metadata generation, making it easier to access and utilize archival materials. As the technology continues to evolve, it is likely that AI will play an increasingly prominent role in the archiving process.

Broadcast Archive Operations

Understanding how broadcast archives operate is essential for appreciating their value. Typically, a broadcast archive is divided into several key functions: acquisition, preservation, documentation, and access. Each of these areas plays a crucial role in ensuring that the collections remain relevant and accessible to future generations.

Staffing and Organization

The staffing structure within a broadcast archive can vary widely, depending on the size of the institution and the scope of its collection. For example, Brecht’s current organization, RSI, has a dedicated team of approximately forty staff members. In contrast, larger institutions may employ hundreds of individuals to manage their extensive collections.

Collaboration with Production Teams

Broadcast archives often work closely with production teams to ensure that valuable content is preserved. This collaboration may involve integrating archival processes with production asset management systems (PAM) and media asset management systems (MAM). By connecting these systems, archives can efficiently manage the flow of content from production to preservation.

The Shift to Streaming and On-Demand Services

The rise of streaming services has fundamentally changed the landscape of broadcasting. As audiences increasingly turn to on-demand content, the role of traditional broadcast archives is evolving. The lines between archives and streaming platforms are becoming blurred, with many archives now offering their collections through digital platforms.

Ethical Considerations in Archiving

As broadcast archives transition to digital platforms, ethical considerations come to the forefront. Archives must navigate the complexities of rights management while ensuring that historical content is accessible. This includes addressing potentially problematic content and providing context to users, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of history.

Preserving History for Future Generations

Ultimately, the mission of broadcast archives is to preserve history for future generations. As Brecht points out, it is vital to acknowledge both the positive and negative aspects of history. By maintaining transparency and providing context, archives can ensure that their collections serve as valuable resources for education and reflection.

Conclusion

Broadcast archives are pivotal in shaping our understanding of history and culture. As we navigate the challenges of digitization, AI, and the transition to streaming services, the importance of these archives cannot be overstated. With leaders like Brecht Declercq at the helm of organizations like FIAT/IFTA, the future of broadcast archives looks promising as they continue to adapt and evolve in the digital age.

For more insights on this topic and to stay updated on the latest developments in broadcast archiving, consider following FIAT/IFTA and engaging with the broader community of media archivists.

Transcript

Chris Lacinak: 00:00

Imagine you’re a future archaeologist trying to understand humans from the early 1900s through the early 2000s. What do you think the most robust, compelling, comprehensive source for obtaining that understanding might be? If I were you, I might be thinking the Library of Congress or landfills perhaps. And in truth, both of those do hold portions of the collections I’m thinking of, but that’s not what I’m going for. I think there’s a strong argument to say that broadcast collections produced and/or held by broadcasting entities across the world is the answer to this question. Radio and television broadcasters have held a unique place in the hearts of people around the globe over the past century and more. In their mission to entertain, document, and inform, they have amassed some of the largest and most important collections throughout the world. Each collection providing deep insights into the time and place in which they were broadcast. Broadcast collections hold the stories of the forming of countries and governments. They hold documentary evidence of culture and politics. They store the comedy, the drama, and the sports that captivated the audiences they reached. Leveraging the power of audio, film, and video, there is arguably no greater record of humanity for this period than the culmination of these broadcast collections.

I’m delighted to have Brecht Declercq join me on the episode today.

Brecht has served on the board of FIAT-IFTA for seven years. In English, this stands for the International Federation of Television Archives, and they are self-described as the world’s leading professional association for those engaged in the preservation and exploitation of broadcast archives. Brecht has served as the president of the organization for the past four years, giving him in-depth knowledge on the state of affairs with regard to broadcasting entities throughout the world. Brecht has also worked with and in broadcast archives for his entire career. Currently, Brecht serves as the head of archives for RSI. The Italian-speaking Swiss public broadcaster. Brecht’s experiences and insights are so interesting and valuable, and I’m excited to be able to share his thoughts and voice with the DAM Right listeners. Remember, DAM Right, because it’s too important to get wrong.

Brecht Declercq, welcome to the DAM Right podcast.

It’s an honor to have you here today. I wanted to have you on the podcast to get a peek inside of radio and television broadcast archives, and you bring a lot to the table there for a variety of reasons. You have worked on and in radio and television archives, and you have been the president of FIAT-IFTA for years now. So I’m really excited for you to bring a sneak peek inside of radio and television archives for our listeners that have not had the opportunity to work within those archives. So thank you so much for joining me today. I really appreciate it.

Brecht Declercq: 02:52

It’s a pleasure. So I’d love to start off with getting some insight into your background, and I’d like to maybe pinpoint, is there one thing from your past, your history, that you bring to the table that you think really informs your approach and how you work today?

Brecht Declercq: 03:12

Well, yeah, it’s of course a difficult question because I’ve been active in this field since 20 years. And I think if you’d ask me like, okay, what was that decisive moment in which you said, okay, this is kind of a career that I could make, that I could feel well in, that decisive moment was in fact in 2010 when I attended for the first time a big international conference. It was in 2010, the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives together with the Association of Moving Image Archivists in the US organized their conference, joint conference in Philadelphia. And that was four days of very immersive encounters, I would say, immersive experiences, attending all these presentations, meeting all these passionate people. And I was very lucky to be there because I had submitted a proposal without even asking my boss. And that was the moment in which I said to myself, sometimes it’s better to ask to be forgiven than to ask for permission. And that’s the one lesson that I drew from that experience. And it was so motivating that it kept on thriving based on those four days only in the US for quite a few years.

Chris Lacinak: 04:39

And if I remember right, you and I first met at that conference, I believe.

Brecht Declercq: 04:44

Yeah, that’s true. It’s actually a quite ironic anecdote, I would say. I was speaking about a workflow to migrate the content of DAT tapes, digital audio tapes. And I remember the room was packed and I was very proud of that. It was not a big room, definitely not with maybe 30, 40 people sitting in that room. And you asked me a question at the end of my presentation, and you were asking whether I had ever heard of interstitial errors. And I was so ashamed at that moment that I had to say no, me standing in front of that audience and say, okay, this guy is asking me one question and I don’t even know how to answer it. But then you reassured me and you said, don’t worry, many people in this room won’t have heard about it. So yeah, that was our first meeting, Chris.

Chris Lacinak: 05:34

An advantageous moment, yes. And I remember you being very, I remember your energy. You were very energetic, very into the, I mean, as was I, but I just remember that about you that you and I spoke afterwards and you were very into the conference and super energetic about it. It’s funny to think back quite a while ago. So we later came to meet again when you were at an organization, and my lazy American accent will always get this wrong forever. I’ve said this word a million times, but so you’ll have to forgive it, give me. meemoo was an organization when we started working together, it was called VIAA. But I’d love to, if you could talk about the work that you did there and what was unique about that initiative and that work.

Brecht Declercq: 06:23

Yeah, I think I’ve explained VIAA, now called meemoo, several times around the globe. And I think it can best be explained by pointing to the pain, the pain that meemoo was solving or is still solving. And that is that the audiovisual heritage of many countries is spread amongst a variety of institutions like libraries, archives, museums, public broadcasters, commercial broadcasters, smaller and bigger ones. And if you thoroughly think about it, and if your national government decides to take a responsibility in that, because that’s not always the case throughout, over the globe, then this comes a very cumbersome duty, I would say. And it can, there is a risk that it becomes a very expensive one. And there is also a need to do it in a very professional way. And that is actually the, meemoo is the answer of the Flemish community, so the Dutch speaking northern part of Belgium to the questions of obsolescence, of degradation of audiovisual carriers and of the increased demand to audiovisual heritage. So what they decided to do is set up, with a government subsidy, of course, set up large scale digitization projects for audiovisual heritage, collecting in fact, all those tapes and cassettes and films, et cetera, et cetera, that were present at so many institutions. We started off in 2013 with around 40 institutions, about 10 broadcasters and 30 libraries, archives, museums. And by now they are at, I think almost 180 of them. And I am proud to say that when I left meemoo about one and a half year ago, about 80% of that whole volume estimated at around 600,000 to 650,000 objects is digitized. So there is still some stuff to be done, mainly film, but that is done. And it was not only about digitization. meemoo also provided sustainable digital storage, because also that can be a cumbersome task for say a small museum or a small library with just a few hundreds of audiovisual carriers. So they provided also that kind of professional storage. You could call it a public cloud. You could somewhat compare it to that. And then they also said, what is the value of all this material if we don’t valorize it not in a financial way, but in a, I always refer to the return on society. So they decided to set up, for example, an educational platform, shortening almost literally the distance between the archival vault and the classroom to let’s call it a few weeks, maybe a few months in some cases, a few days in an extreme case, so that teachers can use those materials in the classroom. And it is indeed a unique construction, but because I so thoroughly believed in it, I still keep on spreading that word because on a, let’s say on a daily basis, I’m confronted with the situation of audiovisual heritage these days in the world. And the number one basic question for so many archives is how are we going to fund our functioning? How can we provide certainty? How can we approach, can we tackle all these huge challenges without certainty about our funding, et cetera, et cetera. And I think that if you manage to convince a government of a very efficient way of dealing with this thing, and you then provide the Flemish example that many governments can be interested in, we’ve seen that in India, for example, and we’ve seen that as well in New Zealand. Those are the only other countries where they, I wouldn’t say copied the Flemish example, but rather got inspired by it.

Chris Lacinak: 10:44

Yeah. Well, it’s certainly, it is one of the most masterful, comprehensive, I think, digital transformations that I’ve seen in that it addresses such a variety of cultural heritage, material types, content. It addresses digital preservation, digital asset management, and as you said, like the outreach engagement to classrooms and to the public and tons of metrics and tracking around that and to measure success. And it’s really a phenomenal initiative, I guess is the word. I’m not sure if initiative is the right word or not, but program, entity, whatever, the effort has been, I think, really phenomenal. So I appreciate you filling us in about that. And we’ll share a link in the show notes to the organization so people can go and check that work out.

Brecht Declercq: 11:36

Yeah. The nice thing about the approach is also, I want to stress is that a lot of the information and the knowledge that they created while doing all this, they’re sharing it for free and in an English version as well on their website. I really want to stress this because it was one of the goals to stress their experience even beyond the Flemish borders, positively deciding to translate stuff also into English and thereby contributing to the spread of this kind of knowledge throughout the globe.

Chris Lacinak: 12:00

Yeah. Well, I wanted to ask you to talk about that because I think it does inform, it’s an important part of your background and kind of the context that you come from. Could you talk a bit about what you’ve done since being at meemoo? Well as I said, one and a half year ago, I decided to leave meemoo, not because I wasn’t having a good time, I was having a great time. I was absolutely having a great time, but it’s always been on my mind to take a challenge abroad. I am Belgian, but I always have had this international outlook. And then a vacancy came up here in Switzerland at RSI. And I kind of know this organization since a while. In 2011, the World Conference of the International Federation of Television Archives, of which I am now the president, took place in Turin in Italy. And I went there by car because some people will know that I have this kind of passion for everything that’s Italian in my spare time. And I went there by car. And when driving back, I came in contact with the Head of Archives here at RSI. And the road from Turin to Belgium actually crosses the town where I’m now living. So I decided to make a stopover and to visit that same RSI. And I was stunned by what I saw because the reason that I stopped was that I wanted to see a very nice innovation, in my opinion, that was a robot, a robot to digitize their video cassette collection, a three-dimensional robot refurbished from the car industry. You know, those orange ones you always see in footage. They had refurbished that and that machine had an autonomy of five days. So for five days, it could continue to digitize tapes, clean tapes, get them out, et cetera, et cetera. And I found that a marvelous innovation. And I wanted to see that. But when I arrived here at RSI, they wanted to show me something else. And that was their speech to text fully integrated with their documentation processes. So we are talking about an artificial intelligence that was already implemented almost 50 years ago. Yeah. They started off with that in 2009. So on not one, but two levels, they were like, yeah, as far as I know, on a global scale, there were forerunners. And I said like, that must be a marvelous organization to be able to work there. So I decided to apply and I’m now Head of Archives. So Head of Archives, meaning that all the archival departments, whether it’s a radio archive is a television archive are under my responsibility here in Italian speaking Switzerland.

Chris Lacinak: 15:04

I want to come back to RSI later, but I want to sidestep and talk about FIAT/IFTA for a bit first. You’ve touched on the organization and what you’ve just said, but I love it. Can you tell us a bit more about what’s the mission of the organization? What’s the makeup of the organization? And tell us a bit more about how the organization works.

Brecht Declercq: 15:26

Yeah. First of all, FIAT/IFTA stands for, it’s a double abbreviation, International Federation of Television Archives, Fédération Internationale des Archives de Télévision. So the French, French.

Chris Lacinak: 15:36

That sounds much better that way.

Brecht Declercq: 15:40

Okay. Well, formally our mission is FIAT/IFTA actively creates and exchanges expert knowledge and promotes and raises awareness of future media archiving by building and maintaining an international network and its broader community, organizing events, developing trusted resources, and taking challenging initiatives for those engaged in the field of media archives. I have to admit that I’d read that. So I don’t know it by heart. So yeah, that’s actually what we’re doing. We’re trying to form a global community for all those engaged in media archive. So our membership typically consists of around 40 to 50% public broadcasters, 10, 15% of commercial broadcasters, and then 10, 15% of very active, what I would call national audio visual archives or national archives and national libraries that are involved in the preservation of audio visual heritage in their country as well. And then evermore, we also have members of the industry. They have a special membership called supporting membership. And then we have organizations like a broad plethora of members, such as FIFA, the International Football Association, the New York Times for a while was a member of ours and several others. So it goes into several directions, but I would say the stronghold is really, or the real focus is really media archives, traditionally television, but evermore venturing into radio and video at large, all these kinds of things. Yeah.

Chris Lacinak: 17:27

And when you say the industry, what do you mean when you refer to the industry? Yeah. Good question. I’d say companies like AVP or all kinds of services and goods providers. Yeah. Service provider digitization companies, but consultants, software developers, evermore also companies in the field of artificial intelligence, MAM and DAM, obviously, they’re very closely connected to our community. So yeah, that’s what I mean with the industry.

Chris Lacinak: 18:05

So you’ve given us a picture of, that it’s a global organization. Can you offer some sort of breakdown of members?

Brecht Declercq: 18:12

Yeah. As I said, our stronghold and our historical background is mainly in Europe, that’s for sure. So we’re talking about, yeah, once again, 40, 50% European members. But I want to stress that amongst our founding members were also American companies, American broadcasters, such as NBC, CNN. Later on, we also got CBC Radio Canada, for example, as a member. In Latin America, we’re also in the realm of public broadcasting, but also commercial broadcaster, for example, Globo, the Globo Group, which is the largest commercial broadcaster of Latin America is a member of ours. Then if you go to Africa, you typically, once again, are with public broadcasters, the South African Public Broadcasting Organization, for example. And if we look at, yeah, the Middle East, then you’re Al-Arabiya, Al-Jazeera. Towards the other parts of Asia, the Japanese public broadcaster was one of our early members, ABC in Australia. So we really have a global outlook, but I do want to recognize that we are mainly Eurocentric, I regret to say, because the ambition is to be global.

Chris Lacinak: 19:38

It still sounds like, I mean, I have attended FIAT/IFTA conferences and they definitely are attended by participants worldwide. They feel very global. So I appreciate the transparent Eurocentric admission there, but I would say that probably FIAT/IFTA is doing a lot better than a lot of organizations in global representation. I know that you have done surveys in the past, in your time, I think even before you were president, you were involved in a working group that did some surveys to the FIAT/IFTA membership. And I think since you’ve been president, you’ve done some of these. I want to ask you to go into all of them, but I wonder, are there any that were particularly interesting in their findings and would you be willing to share maybe what the questions, what was the gist of the questions and what were the findings?

Brecht Declercq: 20:32

It’s true that we do love surveys as an instrument because it’s interesting towards our members and also towards our broader stakeholder group. And a survey that we do on an annual basis is called, “Where are you on the timeline?” And that really says it all in the sense that we’re doing it now this year, probably for the 15th consecutive time. And it’s a really short survey. It’s six or seven questions. I should check that. I’ve run it personally for three or four years. It really asks three, sorry, five, six, seven questions in a very concise way. And it allows the respondents to respond with a multiple choice. So they just pick the answer that fits or that describes their situation best. And the answers are formulated in a progressive way. So you just indicate what stage you are in, in what we consider it when we drafted this survey, a logical evolution of things. And that survey really allows us to see and to monitor the evolution that our members and beyond, because responding is not restricted to our membership, what level, what stage that archives are in. And we’ve seen things evolving up until the point where we are even saying now, like we should add extra options to our scale because things have evolved so much. And we see so many archives reaching those final stages that we had foreseen, I would say so many years ago, that we really have to extend that survey again. So that timeline survey is really a nice quote, but there have been others. We have been doing surveys about media asset management systems, for example, about metadata creation and the way how organizations create their metadata and how they look at that and the evolutions they expect there. So yeah. And sometimes we also give it a regional focus and that’s also very enlightening because that’s when our members really say like, okay, this allows me to compare, but really with comparable situations. So yeah.

Chris Lacinak: 23:03

I want to come back to the regional focus later. That’s an interesting point. I’d like to ask, I guess, in the surveys you’ve done, maybe, we’re about halfway in between the FIAT/IFTA World Conference, it was in October, so we’re about halfway to the next one and halfway past the last one. But between the conference, what you see happening in the conference and between those surveys, could you give us some sort of summary about what you see? And of course, it’s a large body of members. So any insights that you could share about what’s the state of affairs related to broadcast archives across the world?

Brecht Declercq: 23:45

Yeah. It’s hard to answer that question in a mono-directional way.

Chris Lacinak: 23:53

It’s a very unfair question. Yes.

Brecht Declercq: 23:56

Yeah. On a global scale, the situation is very different. I’ve been privileged enough to travel the world and to see broadcasters archives on every continent. And the situation can be very different, even within one region. It often depends on the, well, let’s say it like it is, the financial and budgetary wealth of a certain country. But apart from that, the evolutions that I’ve seen throughout the years, and people who are a bit longer active in this field will definitely recognize that, is that real wave of digitization that has conquered our field, I would say. And digitization, not only in terms of the digitization of working methods and the whole environment in which media is produced, but also in terms of archival digitization. So already in the mid 2000s, there were some alarm bells going on everywhere in the world, like, okay, this is happening. And then around 2010, 2013, if I’m not mistaken, a few very prominent audiovisual archivists in the world, I always quote Richard Wright from the BBC and Mike Casey from Indiana University there, they were warning and they were saying, beware, dear colleagues, because somewhere around 2023, 2028, to digitize large quantities of magnetic media, either audio or video, will become practically unaffordable. Not impossible in the sense that technically machines will stay around, some machines will stay around. If you have a huge collection and several hundreds of thousands of these audiovisual carriers, such as radio and television stations typically have, then things might become unaffordable. It’s going to cost so much money to have those carriers digitized that you’re not going to be able to pay it anymore. And actually that wave is now, I would say, coming to an end in some parts of the world. There are several broadcasters in the FIAT/IFTA membership, for example, that have finished digitization. My own employer here in Switzerland at RSI, we have practically finished almost everything. I think we’re at 98% or so. We’re just thinking of re-digitizing some film material, but that’s it. But there are indeed many broadcasters still in the world that haven’t digitized everything yet. I was in Tunisia a few weeks ago and I hesitate to say this because I don’t want to blame anybody, but we have to look reality straight in the eyes. And reality is that we are losing that battle. We are losing that battle and it’s important to be aware of that. In the poorer parts of the world, what Mike Casey, I already mentioned his name, what Mike Casey has called degralescence, this portmanteau concept of degradation and obsolescence is striking and it’s striking first in the poorest parts of the world. I thought first it was a coincidence, but when I started thinking about it, it wasn’t. In the last two days, I received two notifications, two emails from broadcasters and I won’t mention their name because that doesn’t make any sense, but from poorer parts of the world asking whether I considered it possible in their country to have two inch open reel video tapes digitized and my clear and honest answer was no, not even in your neighboring countries. So yeah, that degralescence is striking. We are coming at that point now that was predicted so many years ago by so many people. So that’s an important evolution that I want to point to. Another one, and it’s partially overlapping now, is that AI wave. It’s undeniably so. It has been for long predicted. It has been predicted for so long in the broadcast world. As I said, as early as the early 2000s, we were all talking about it. The world was buzzing like there is this new technology that’s going to take over the documentalist’s job. And then the strange thing is that we had to wait for it so long that some in the media archiving world already started to doubt. They said like, “Isn’t it all rumors? Isn’t it all like fake news almost?” And my answer, my personal answer was always like, it’s not a question of if, it’s a question of when. And if you’re seeing now how quickly things are going, I am still convinced that broadcast archives were amongst the first parts of the media industry that adopted artificial intelligence first. And we were very aware of what was coming, but then still we were surprised by the speed that it actually made throughout the last, let’s say, two years after the launch of ChatGPT and DALL-E, everything changed, of course. So that’s that other wave that I’ve seen coming. Yeah, I do.

Chris Lacinak: 29:57

You’re right. I remember early mid 2000s, a lot of hype around AI and just major disappointment on the execution and delivery of the promise. And it did take a while. Yeah, it took 10, 15 years before it came back with something that was impressive enough to grab people’s attention. Although we did see lots of organizations doing smaller, interesting kind of proof of concepts along the way. I want to go back to, you touched on, and this touches on, you talked about the regional nature of your surveys and things. You talked about how countries with less resources are suffering, kind of the lack of digitization. Can you help people understand what’s lost if these materials are lost to degradation and obsolescence? What, you know, across the globe as you look, what are some things that we miss out on both regionally but globally in our understanding of the world that goes along with the media that’s lost?

Brecht Declercq: 31:04

Yeah, that’s a very good question. But because I, every now and then I have to give that answer to make people aware. But I’m going to give you a very, very simple answer. Let’s have a look at the, let’s focus for a second on Africa. The African wave of independence, so that started off around the mid-50s in Ghana, it was Kwame Nkrumah, which was an African leader of, a great charismatic leader. And I’m not going to tell the whole story of the independence of Ghana, but my point is that’s where it all started off and it continued up until the 70s, that wave of independence. But that is also the era in which broadcasting, television production was actually switching gradually from film recording onto video recording. So that era is the era in which, from which we have the oldest videotapes. Also in those countries, you have to be aware that the countries that those African countries became independent of were mainly, as we know, European, Western European countries, France, Great Britain, Belgium, my own country. And those television systems in those countries had been installed by those colonizers. So they were also the ones that provided technology and that decided about the technology and that was videotape evermore. And after that independence, of course, those broadcasters, those public broadcasters, they became independent institutions under the wings of their governments, of course. And they are still now preserving their archives. But once again, I’m not blaming anyone here, I’m just describing a few facts. In many African countries that became independent in the 50s, 60s, 70s, those archives are in a dreadful state. So what these archives are losing and what their countries are losing is the audio visual documentation of their birth.

Chris Lacinak: 33:25

Wow.

Brecht Declercq: 33:26

So take a second to think about that. Take a second to take the American Declaration of Independence. Can you imagine that you would say, “Ah, sorry, we can’t read it anymore.” That’s what happening now in Africa, now as we speak. That’s what happening. And then take this on a global scale and then I would say like, “Okay, let’s make a little comparison.” Try to imagine today’s world and the importance of audio visual media and try to be aware that also throughout the course of the 20th century, many, many historical evolutions were documented on radio and television. Television and radio were amongst the most popular media and the most influential media in the 20th century. You cannot explain the rise to power of Adolf Hitler without acknowledging the role of radio. So try to imagine that we would lose that kind of heritage. Try to imagine that we’d have to explain history without having access to radio and television as historical sources. It would simply be impossible. And then now I quit, I rest my case.

Chris Lacinak: 34:44

Yeah, wow. Well, you can imagine. So, I mean, just to kind of reiterate and follow up on what you just said, the fast forward, 50, 100 years, I would say even with the presence of archives, it can be difficult to represent the true narrative of history. But the source material is there, right? Imagine the picture you’ve just painted. In many cases across the world, the source material is lost. Just what a major shaping of the historical narrative takes place from that could, and I would say it’s probably likely to misrepresent what’s happened historically across the globe. That’s major. You make a very good case.

Brecht Declercq: 35:36

Can I point to one simple example as well? Just a very small state on the globe, it’s called Timor-Leste, Portuguese for Eastern Timor. It’s a small island close to Indonesia. And that country became independent in the 90s. And there was a, if I’m not mistaken, it’s a French German cameraman called Max Stahl, and he documented all that was going on in the independence war, because that country has become independent from Indonesia. Now filming there, that cameraman has filmed a lot of the violence of the Indonesian army throughout that war of independence. That archive in itself is documenting the birth of Timor-Leste in the 90s. Luckily, that archive was saved at some point, also thanks to the intervention of INA, the French National Audiovisual Institute. But that is another example of a country that could have lost the documentation of its birth, paired with, let’s say it like it is, crimes against humanity during that war of independence. So, it demonstrates once again that unique documentational role of not only of media corporations of course, but also of audiovisual heritage in general.

Chris Lacinak: 37:10

Do you have feedback or requests for the DAM Right podcast? Hit me up and let me know at [email protected]. Looking for amazing and free resources to help you on your DAM journey? Let the best DAM consultants in the business help you out. Visit weareavp.com/free-resources. Stay up to date with the latest and greatest from me and the DAM Right podcast by following me on LinkedIn at linkedin.com/in/clacinak. I want to shift away from this specific topic, but stay in the general theme of kind of differences and discrepancies across the globe. And I’m going to maybe just focus in a bit on, well, I’ll ask you to paint a picture for us, but maybe we can use kind of Europe versus the United States as a place to focus in on in particular, which is, I think a lot of people, if you haven’t been in the field, you may not recognize just how different broadcast operations look in various countries. And here I think of both the commercial versus the non-commercial nature, the public kind of government backed broadcasters versus commercial broadcasters. Can you paint a picture for people what some of those differences look like and how they operate, how they’re funded and what the meaning there is?

Brecht Declercq: 38:39

Yeah, it’s true what you say, that there is often a very big difference between, I would say, profit driven and non-profit organization in that respect. For what I see or what I know from my daily experience, I haven’t worked for a commercial broadcaster yet, but what I know is firsthand, testimonial by people who work there is that typically a commercial broadcaster has less of that heritage perspective. And that’s okay, that’s perfectly legitimate, I’m not saying that they should. But when you are in a public broadcaster, there is this double perspective always, there is always this double perspective between on the one hand, and this is something they have in common with commercial broadcasters, broadcasters archives are always there in the first place to support their own production, their own production departments. And that’s what they typically cater for, I would say. But at the same time, there is always this perspective of a contribution to society. A public broadcaster’s archive is always supposed to help external customers as well. And external customers that often don’t have a commercial perspective at all, libraries, museums, whether they want to access those archives in a small kind of way, just asking for one or two tapes or one or two clips or so, or whether they want to use it really on a structural scale to open it up towards the whole educational world and the whole school system, etc., etc. And as a public broadcast archivist, you can barely, you can’t barely say no to that kind of requests. And it’s not an intention either. I mean, I always say like, without use, a broadcaster’s archive, a broadcaster’s, a public broadcaster’s archive, their shelves are empty, if you understand what I mean. This kind of what I call a heritage perspective, contributing with the archives to the society’s needs without the requirement of earning money with that, that is a perspective that is always present in a public broadcaster’s archive. In a commercial broadcaster’s archive, and I’ve seen that several times, that kind of perspective is absent or close to absent. And that gives them the liberty to take decisions with their archive that I, as an historian, sometimes regret. But you can barely blame them for that because in many countries, there is no such thing as what is called a legal deposit, the legal obligation to deposit a copy of what you have broadcasted to some kind of institution that then preserves it and in the longer run, respecting copyright, et cetera, et cetera, in the longer run gives access to it, such as it happens with books. So many countries in the world have a legal deposit for books or any kind of written publication. So little countries in the world have a legal deposit when it comes to audio visual publications and especially radio and television broadcasts. And that’s the difference in the perspective that I see so often. It doesn’t exclude that some commercial broadcasters do have that heritage perspective as well in certain parts of the world and I really respect them deeply for that because they are often not obliged to do so. On the contrary, the driver that they often have much more is a profit-driven driver. So they often really consider their archives as a source of income. And once again, that’s perfectly legitimate, but this is a whole completely different perspective. For them, it’s a way to valorize in a financial way what they have. It’s really assets in the true sense of the word, on condition of course, that they’re findable and that they have the rights to exploit them in a financial way, of course. But it’s a completely different perspective. And just as a side note, in FIAT/IFTA we bring those two together so you can imagine how difficult it can be to unite those two perspectives sometimes.

Chris Lacinak: 43:28

I feel like I have seen instances of broadcast archives that are not commercial also trying to valorize their archives in order to create a more sustainable kind of business model, even when it is a government-based institution. Is that right? Have you seen that as well? Yeah, that’s correct. That’s absolutely correct. Let’s not deny that. Many public broadcasters’ financing is public financing is under heavy pressure in many countries which you see is currently, for example, in Slovakia, the government is threatening heavily the financing, the funding of public broadcasting. And so public broadcasters do all they can to mitigate that kind of effects by searching for other sources of revenue and selling or licensing archival materials are for many broadcasters one of their many ways to counter those effects. And that for me doesn’t necessarily mean that it is a big source of revenue. We have to be honest about that. There are not many public broadcasters archives that can fund, I would say not even two or three full-time equivalents on an annual basis with what they sell in terms of footage. That’s something to keep in mind. There is no, in my opinion, there is no sustainable financing model for public broadcasting based on the licensing of footage or archival material. I’m very sorry for those who believe in that, but I don’t.

Chris Lacinak: 45:19

Yeah, that was years ago there was a concept I was running with around cost of inaction, which was kind of, you know, looking at the traditional return on investment. And because I had within organizations of all types, broadcasters, non-broadcasters, universities, you know, all sorts, this concept that usually executives in the organization would hold around, how can we see a return on investment on our archives? And it just, it never calculated out to be advantageous. And it seemed to always lack a holistic perspective on what the true value was. If you, you know, it wasn’t, it didn’t just come down to dollars. And while that’s obviously important, funding is a critical issue that when you look at it alone, it never seemed to do the issue real justice. And some of the things you talked about earlier really paint a picture about the value of these archives.

Brecht Declercq: 46:17

Yeah, if I can just intervene because I want to add a perspective. In 2013, there was a research by the Danish public broadcasters archive. And what they did was for one week, seven consecutive days, 24/7, they recorded the full broadcasting, the full broadcasting schedule on their two main channels. And they measured the duration of all the content that was being broadcasted. And they make the distinction between broadcasted for the first time or not broadcasted for the first time. They came to the conclusion that 75% of the broadcasting schedule, the duration of the broadcasting time was not filled with content that was broadcasted for the first time. And they said, this means that this content has passed through the archive, 75% of that broadcasting time. And if you take a look from that perspective, you could say it’s probably not an exact calculation, but you could think like if we’d have to fill all that time with new productions or with acquired stuff, broadcasting would probably cost us three to four times as much.

Chris Lacinak: 47:45

That’s interesting. Right.

Brecht Declercq: 47:48

It’s an interesting perspective because you never get to think about things that way. But yeah, and it’s not exact, of course, that measurement, but it switches your mindset.

Chris Lacinak: 47:59

Yeah, absolutely. That’s a good framing. Well, I want to jump into, we’ve talked kind of up high, I’d like to jump into what does a broadcast television archive look like? And we’ve just talked about all the disparities and differences. So obviously I want to lean on your personal experience here. Can you offer some insights into, for someone who maybe has worked in digital asset management, has worked in archives, but has never worked in a radio and television archive. And here you’ve had the experience, at meemoo you saw all sorts of organizations. So broadcast was just one source. There was lots of others. But you do have some unique perspective here. Can you give us some insights into what is a radio and television broadcast archive look like? How’s it staffed, organized, those sorts of things?

Brecht Declercq: 48:55

Yeah, let’s first start off by saying that the size of the country usually does not necessarily coincide with the size of the broadcasters or the size of the broadcasters archive. The determining factor is how many channels they have had throughout their history. That typically describes the size of the collection, if we talk about that. So typically in any kind of country for a long while, you’ve had like for a while, one channel, then a second one, then a third one, and four to five, and then some regional channels, et cetera, et cetera. And then television came in the fifties and they started with one channel, they added a second, sometimes a third or a fourth, et cetera, et cetera. And then you’re venturing into the 21st century. And typically that created up until, let’s say the end of the nineties, the start of the 21st century, that created collections about say 400,000 to 500,000 hours of film and videotape. And often taking into account that a lot has been lost, 200,000 to 300,000 of hours of radio or broadcasted radio content, taking into account as well that typically the music programs are not being preserved because their content is not considered unique. So there you have an idea about the size of those collections. And then take into account that in the 21st century, when the MAM systems came up, television and radio archives were much better prepared and much better able to preserve everything that they were broadcasting. So then you’re really talking about an explosion of content. And these days, it’s absolutely no exception that you come into a broadcaster’s archive and you meet say collections of more than a million hours of television content, six, seven, 800,000 of hours of radio broadcast content. And then when it comes to the structure of these archives, once again, up until I would say the nineties, the early 2000s, many, many broadcasters, public broadcasters and also commercial ones had a distinction between their, if they were making radio as well, it was a distinction between television and radio and they had separate archives. That also had historical backgrounds. And I could talk about that for ages, but I’m not gonna do that. But in the 2000s, many of those radio and television archives, they merged within one organization. They became one up until a certain extent, of course, because there were some differences in the processes. And well, what they do is I tend to keep things clear and to say like their typical activities are situated in acquisition and preservation. Yeah, well, the broad domain of acquisition and preservation. And then they intend to invest a lot of their resources also in documentation and cataloging, a lot of their resources, because those processes were the most labor intensive typically, and also therefore the most expensive. And then a third domain of activities is in access and valorization, either internally by delivering their content to their own production environments or by selling footage sales and or by developing all kinds of platforms or websites to which the larger audience or specific target groups within society can access those archives. And there’s a difference, as I said earlier on, between the public and the commercial broadcasters.

Chris Lacinak: 53:01

Yeah.

Brecht Declercq: 53:02

So that gives you an idea. And then maybe what you said about the number of staff. Well, it strongly depends. It strongly depends. Here at RSI, I have a team of about 40. But the General Secretary of FIAT/IFTA, Virginia Bazán, she is now head of archives at the Spanish public broadcaster, RTVE. And if I’m not mistaken, her staff is between 350 and 400 people. So yeah.

Chris Lacinak: 53:32

I want to come back to staff and kind of what your staff does, but I want to touch on something. As you were talking, I just had the thought we were talking about differences and types of archives. I just want to say in my experience, I mean, you’re talking about preservation and archiving as a role within the organizations you’ve been in, and those have been public broadcasters. I would say that there is a big difference I’ve seen between broadcasters in that it sounds like I’m going to guess that the organizations you have worked for have had a mandate or a mission of some sort to preserve and archive. In other broadcasters we’ve worked with, they may or may not have a mandate, but they might have a very strong business case. They have content that they can monetize and it’s very popular content. And so they have a business case to preserve an archive, even if they don’t have a mandate, which has implications because for the stuff that is less popular or less monetizable, then that tends to get lesser treatment. So a mandate would typically cover things that are both popular and non-popular. So there are implications to having a business case without a mandate. And then there are organizations that we have run across many of who don’t have a mandate and don’t have a really strong business case whose collections have either been thrown in dumpsters or saved from dumpsters by a university or some other entity that sees the cultural value and grabs it because they see it, even if the organization that created it doesn’t. So I just want to point out that difference across different organizations.

Brecht Declercq: 55:12

Yeah, you’re absolutely right. You’re absolutely right in that. Yeah, definitely. It’s an observation that I’ve made as well. And there are some regional differences in the world as well there, I think.

Chris Lacinak: 55:24

Let’s come back to the staffing. For your organization that has 40, I think you said 40, four zero, right?

Brecht Declercq: 55:30

Yes.

Chris Lacinak: 55:31

Okay. Can you just describe some of the, like, what are some of the roles and responsibilities tasks? I guess I wonder, how does it bump up against, how does your operation bump up against kind of the production side of the operation? And then on the other side, like on the distribution, publishing, access side, what’s the division of roles and responsibilities on what you all do? And I guess maybe one thing to focus on in particular would be like description. Like how much metadata and description is there on the way in? How much do you guys do? And then how much is there done post?

Brecht Declercq: 56:04

Yeah, that’s a very good question because exactly that point that you’re talking to is in, it’s currently, that’s my feeling, it’s being revolutionized by AI amongst others. And a typical situation I would say in a broadcaster’s archive currently is that there is a production, let’s limit ourselves to television only for now, because radio is somewhat parallel there, but you have a production platform and several production systems and post-production systems circulating around a, what you would call a PAM system, a production asset management system. And then from the archives part, connected, often connected to that PAM, you have a MAM, a media asset management system. And those two are often connected to each other and that situation might differ from organization to organization, depending on how they look at things and where they situate their archive exactly at the right in the middle of the production process or at the end of the chain of production. That is still a point of debate with many broadcasters archives. So typically what you see is that broadcasters archives try to connect their systems in such a way that as many descriptive, administrative, and technical metadata are inherited by the archival databases coming from all kinds of production systems. And so they connect these systems to each other through APIs and other kinds of protocols, I would say. And then they try that way to limit the manual work that still has to be done by the documentalists. That is a typical situation. But as I said, it’s in full evolution there because what is jumping in is AI. And so what we have seen throughout the history is that four big groups of metadata creation have grown, I would say. And those are like the old school manual work by documentalists that has been around for 80 years, say. Then inheritance by true production systems, inheritance, what I just described, like connecting PAM and MAM systems and inheriting as much metadata as possible. And then a third group, which is kind of a bit off the radar these days, but nevertheless interesting is what we used to call user generated metadata. The metadata that users that are involved in documentation processes via any kind of project, for example, could create and then deliver to the archive, but also in conscious ways of doing that. And I tend to call that consumer generated metadata. The fact that you watch a clip for only 5 seconds and not for 10 seconds is what I would call an interesting consumer generated metadata for the archive. It all has to do with media companies being data driven these days. And the fourth way of generating metadata is the broad world of AI, what I would call automatically generated metadata in some way. Now, what I had been thinking 10 years ago is that those four groups would always be combined and they’re covering up for their weaknesses and strengths and finally result in a fully filled up archival database. What I’m seeing now is that the quality of the results of artificial intelligence algorithms is increasing so quickly and the cost of, for example, connecting MAM systems and PAM systems and all kinds of systems that could provide metadata, that cost is so high that is quickly being overhauled by the evolution of AI algorithms. Also because all those several systems within a broadcaster, within a media production, they all have what I call asynchronous life cycles. Their technologies evolve in their own way and many, many broadcasters, they call upon the service of external providers or they tend to use a plethora of systems and to make them communicate to each other has become impossible. And then all of a sudden AI is there as well and obtains results that are nearly as good and often cheaper.

Chris Lacinak: 61:26

Could you put some more clarity? I just want to talk a bit more on the, you talked about PAM and for listeners, I’ve heard PAM recently, but on the CPG, consumer product side for product asset management. So this is not that, this is production asset management, which is… In the kind of production and post part of the organization. And you mentioned MAM, I wonder in your experience, where have MAM and DAM lived in an organization and how does that interact? How does the archive interact with that?

Brecht Declercq: 62:02

That’s a good question as well, because when I first contributed to the development of a MAM system that was in 2006, 2007, when I was working for the Flemish public broadcaster VRT, the reasoning was that a MAM system would be the, I would say the spinal cord of media production and the archives main database at the same time. So the theoretical background to that, and I wish to refer to one author in particular, that’s Annemieke de Jong from the Netherlands Sound and Vision, Netherlands Institute for Sound, but she did a lot of work around this. And she said like, what we see is that the archive evolves from being at the end of the production chain into the center of the production chain. And she was right, her theoretical thesis was absolutely correct. But still that didn’t really happen. I don’t know why, it’s hard to say why it didn’t happen completely as she predicted. But I do think that many broadcasters have been bringing in the expertise of audiovisual archivists into the center of their production environment because they acutely became aware of the importance of, yeah, I can’t describe it with other words than managing their assets. And whether you do it with the aim to, I would say store them for the longterm or store them to be reused the day after, I would almost say, what’s the difference?

Chris Lacinak: 63:52

The practices are the same.

Brecht Declercq: 63:54

Yeah. Yeah, you could add, for the archivist, you could then come up with the whole story of digital preservation and longterm preservation, tens of years, et cetera, et cetera. That’s a world in itself, I would say. But often, and this is also what makes broadcasters archives a bit particular, often that kind of subjects, that kind of challenges are tackled by the IT departments. Strangely enough, because radio and television archives, they have been also logistics guys and gals, but the whole digital logistics part is now covered by IT engineers that are not working anymore for the archives department.

Chris Lacinak: 64:44

And what I’ve seen in broadcast operations too, I mean, you have, of course, scheduling systems, which are their own kind of asset management components. My view is that the landscapes within broadcast operations with regard to digital asset management are typically more complex than in, say, a corporate archive or a corporate entity where you have some very specific spots you tend to see DAM, MAM, PAM, those sorts of things. I want to shift a bit towards talking about as broadcast operations or broadcasters move more towards on-demand and streaming as being the primary driver, I’ll say. What are the implications of that to the archives within these organizations? Are there implications there?

Brecht Declercq: 65:39

Yeah, definitely. I think this is also an evolution to which I think many archivists have been looking forward because it stresses the importance of the archive. And on an annual basis, I contribute to the call for papers of the FIAT/IFTA World Conference. And this year, and it’s not the first time, I really pushed to have one theme in this call for papers that is like OTT platforms, over-the-top platforms or streaming platforms or archival catalogs. What’s the difference? That to me is an intriguing question. We are evolving ever more with broadcasting, with television towards a world, and it might even be more the case in the US than it is already over here in Europe. We are evolving ever more into a situation where linear broadcasting is becoming a marginal thing. And I even foresee within a few years the closing down of television stations. The general director of the BBC has announced that there won’t be a linear broadcasting by the BBC anymore by 2030. I think that’s realistic. And then the question becomes what those broadcasters, if you can still call them that, those media companies are offering is content, right? It’s content on any kind of platform. And what the archive has been offering is content as well. It might not be content that is recently produced. It might be content that has been produced a bit earlier, but the border between the two is ever more getting irrelevant. And I remember illustrating that evolution towards people who inquired with me about it, by saying like, for you, when does the archive begin? If you have to count back from now, from one second ago, you’re listening to the radio, watching television, when does the archive begin? And most people then say like, hmm, maybe one year ago or 10 years ago. Then my answer is, how can you reasonably sustain such an answer? It doesn’t make sense. It for me, the archives begin tomorrow because in our archive, as we speak, the interview with the Pope that I just referred to was already in our archive a month before it was spread worldwide. So we already have stuff in our archive that is like not even yet broadcasted. So it’s coming ever more together. The lines are really blurring there.

Chris Lacinak: 68:45

So does linear broadcasting then gets replaced by platforms for watching and listening to content and the linear component, I guess, the kind of curation gets replaced, I guess, by recommendation engines and things like that, that seem to look at the behavior of the consumer and tries to feed them content they think they’ll be interested in. Is that what the future looks like, you think, for broadcasts?

Brecht Declercq: 69:14

Yeah, I don’t think I’m saying revolutionary things if I agree with you. Yeah, that’s how I look at things. And then the question for the archivists, but also for the person responsible for filling those platforms could be like, what kind of things from our huge catalog of recently produced or long time ago produced stuff are we going to publish today? I mean, I want to illustrate this with a very, in my opinion, a very interesting evolution. So in France, the archive of the public broadcaster and of so many other broadcasters is managed by the Institut National d’Audiovisuel, a French National Audiovisual Institute, which is one of the biggest audiovisual archives in the world. And they have decided to call themselves since last year, a media heritage company. They have their own streaming platform. They are, I would say, as much a streaming platform as Netflix is. That says it all to me. It says it all. They’ve just evolved into something Netflix like or something Disney like.

Chris Lacinak: 70:39

What are the ethical considerations here? I mean, do you just open up the archive entirely? How does rights play into that? How does content that this station may want to put some sort of moderation or context around that’s historic and maybe problematic in some ways? What do you think that looks like?

Brecht Declercq: 91:02

That’s also a very intriguing and very interesting question. I’m really aware of the sensitivity of this subject just because our broadcasting history, our media history is almost, it’s touching for many people is touching upon almost what I would call their identity. And that once again proves between brackets how influential television has been throughout its history. If people find their favorite programs from their favorite channels that have been broadcasted so many years ago and that colored their youth, if they find that so important, well, that shows how impactful television in particular, but radio also have been. But this might be also a bit of a European standpoint, but I think in Europe, our answer, although it took us some time to learn to deal with this, but I think we recognize, I’m really careful choosing my words here. I think we recognize that broadcaster’s archives are undeniably reflecting their own history and the history of human conceptions and human ideas throughout history. And if we want to look history in the eyes, we also have to look into the eyes of the more painful parts of our history. And let’s make no mistake, for example, the use of language evolves with humanity. And I always say, who knows which kinds of words that we pronounce now without asking ourselves any question, which words will be considered in 50 years from now, very problematic. We don’t know that yet and the people who pronounce those words 50 years ago, they in some cases have been unrespectful also. There are some words that were a hundred years ago already insulting and still they were used 50 years ago, but they have been used. And as an historian, it’s my opinion that you cannot falsify history. What you can do as an archivist is point to those problematic episodes of your own history and say, look, what we are showing you here is not intended as a source of entertainment, not necessarily. Please consider it as an historical document as well that was made in an era with certain values, applicable editorial values, editorial guidelines applied in the era of production. And today we adhere different norms. And if you think that this would be insulting to you, we’re warning you already that this might occur, but we’re not going to hide it because it is our own history and it’s a difficult part of our history now today, but it’s there. And you could then argue like, do you have to publish it in such a public way? Shouldn’t you just keep it on a sidetrack that is only accessible for historians or so? That’s a different discourse as well.

Chris Lacinak: 74:50

When you say, I just want to clarify, when you say you can’t falsify history, I take that to mean that what you’re saying is you can’t hide the ugly parts away and just show one part that would be a falsifying of history. Is that the right interpretation of what you just said?

Brecht Declercq: 75:08

Yeah, correct. Correct. And I realize how problematic this might be, but it’s the historian speaking here. And yeah, it’s a debate that is not yet finished. And I see it also on OTT and streaming platforms all over the globe that broadcasters and media companies tend to consider this question in a different way. And it also has to do with how they interpret their own role. I find it perfectly legitimate that a company like Disney says, look, our streaming platform is not intended as an historical source. And it’s intended as a form of entertainment. Those historians who would want to watch the original things, because for them, for their historical profession, it’s important that they can access authentic sources. For them, we have other ways to show them. What I mean is it depends of your mission.

Chris Lacinak: 76:18

Yeah, I know that’s a very interesting kind of dissection of you’ve got. Because it would be easy to look at broadcast all as under the entertainment umbrella. I think that’s probably how most people would think of it. And so it’s interesting to just kind of put that point on there to say that in some cases it’s in the mission of the organization, that there’s a historical documentation component, perspective, lens, and then there’s an entertainment perspective or lens. And those are two different animals that may get treated in two different ways. Yeah. Well, let’s wrap up here. You’ve been very generous with your time. And before we started, you said you’ve got more work to do today. It’s already late where you are. So I don’t want to keep it too much longer. But maybe could you tell the listeners when the next Fiat IFTTT conference is and where it is?

Brecht Declercq: 77:15

The next FIAT/IFTA World Conference takes place from the 15th to the 18th of October in Bucharest, Romania, hosted by the public broadcaster of Romania, TVR.

Chris Lacinak: 77:24

That sounds like an interesting and fun destination to go to as well as a great conference.

Brecht Declercq: 77:30

Yeah, definitely.

Chris Lacinak: 77:30

And I’ll share a link in the show notes to the conference or into the FIAT/IFTA site so folks can find that if they’re interested in finding out more. I’m going to wrap this with a question that I ask all of our DAM Right guests, which is, what is the last song that you added to your favorites playlist? Feel free to look at your phone.

Brecht Declercq: 77:57

And now this can be a very shameful moment.

Chris Lacinak: 78:00

It lets us…

Brecht Declercq: 78:02

Okay, no, it’s not so shameful. It’s not so shameful. It’s “The Way It Is” by Bruce Hornsby and The Range.

Chris Lacinak: 78:08

All right, a classic, classic song.

Brecht Declercq: 78:10

And also you could say it’s an archival… It has been archivally reused. Several times.

Chris Lacinak: 78:20

What was the circumstance? Did it come up on shuffle or something? You’re like, “Oh, I have to add this to my liked list.” Or did you seek it out because you remembered it? How did it come to end up on your favorites playlist?

Brecht Declercq: 78:32

Yeah, it’s got a great melody in my opinion. But it’s, you know, that piano. I’m always intrigued by how musicians come to that kind of genius melodies, you know? And that, no, it was just pure coincidence. I was driving in the car and said like, “Oh, I want to hear that song.” And then I said like, “Let’s add it to my favorites list.”

Chris Lacinak: 78:54

Yeah, that is a great song. Great. Well, Brecht, I really appreciate your time and all the super interesting and valuable insights you’ve shared today. I thank you very much. Thanks for your service to FIAT/IFTA II as the President. And yeah, I just, I think the listeners are going to really love this episode and we’ll get a lot out of it. So thank you.

Brecht Declercq: 79:18

It’s been really a pleasure to talk with you, Chris.

Chris Lacinak: 79:21

Do you have feedback or requests for the DAM Right Podcast? Hit me up and let me know. Visit [email protected]. Looking for amazing and free resources to help you on your DAM journey? Let the best DAM consultants in the business help you out. Visit weareavp.com/free-resources. Stay up to date with the latest and greatest from me and the Damn Right Podcast by following me on LinkedIn at linkedIn.com/in/clacinak.

Recap of the Henry Stewart Creative Ops Conference 2024

23 May 2024

Welcome to our recap of the Henry Stewart Creative Ops Conference, which recently took place on May 16th. The conference offered a wealth of knowledge across four tracks: creative operations, photo studio operations, design operations, and creative production. Both Kara Van Malssen and Chris Lacinak attended and are here to share their insights and key takeaways.

Overview of the Conference

The conference was packed with sessions that made it tough to choose which ones to attend. Kara opted to jump between various tracks, while Chris focused primarily on creative operations. This approach allowed them to gather diverse perspectives on the evolving landscape of creative operations.

Key Takeaways

1. Creatives Doing More with Less

A recurring theme at the conference was how creatives are adapting to do more with fewer resources. With increasing demands from stakeholders and evolving audience needs, many are forced to innovate within constraints. One notable example came from JJ Pagano of Paramount Pictures, who shared how they reduced the time taken to create content significantly through automation and AI. This shift has led to astounding efficiency gains.

2. Creating More from Less Content

The second takeaway highlighted the importance of creating more with less content. This idea again ties back to efficiency. Several panels discussed the need for a master creative asset that could be repurposed into various derivative forms. Nickelodeon shared how they adapted during the pandemic by repurposing existing content into new formats, such as puppet shows.

3. The Role of AI in Creative Processes

AI was a significant focus throughout the conference. Many speakers addressed the anxiety surrounding job security in light of AI advancements. However, there was also optimism about AI’s potential to streamline mundane tasks, allowing creatives to focus on more impactful work. Dax Alexander emphasized that AI is here to stay and that embracing it is essential for future success.

4. Change Management in Creative Operations

Change management emerged as another critical theme. Dax discussed the cultural shift necessary for adopting AI technologies, stressing the importance of leadership support and clear goals. The idea that change is not permanent resonated with many attendees, reinforcing the need for adaptability in a rapidly evolving industry.

5. The Relationship Between DAM and Creative Teams

Lastly, Tony Gill shed light on the often-fractured relationship between digital asset management (DAM) systems and creative teams. He pointed out that many enterprise DAM solutions do not cater to the speed and collaboration needs of creative operations. This mismatch can leave creatives feeling unsupported, relying on outdated methods to manage their workflows.

Final Thoughts

The conference was a resounding success, with engaging discussions and valuable insights. Both Kara and Chris appreciated the opportunity to connect with industry leaders and peers. The final session, which brought all the moderators together for a recap, was particularly well-received, fostering lively discussion and engagement among attendees.