Article

Ghana

23 May 2011

Things That Shouldn’t Be Archived #9 — Practice Doesn’t Make Perfect

18 May 2011

As you no doubt heard, the Original Champagne Lady Norma Zimmer passed away recently. This was sad news to me because I felt rather a close connection to Lawrence Welk’s stable of performers. Though I didn’t grow up during the height of its popularity, The Lawrence Welk Show reruns have been a staple of Public Broadcasting for decades. And, I don’t know if this makes me sound incredibly cool or like the nerdiest loser around, but, I spent many a Saturday evening in college eating dinner with the show and concocting elaborate, imaginary backstories for the performers, stories full of dark character flaws and tense relationships that betrayed their happy family onscreen presentation.

Ah, youth! And the entertainment options of the low income college student! Anyway, one of the actually interesting things about watching Lawrence Welk was seeing all of the patterns and repetitions that occurred over the years, or even within shows: Costumes and sets re-used, camera angles and edits (and the same exact camera progression used for the first half of a song and the second half), and the Welkian set of standard songs.

Unfortunately, the same way that costumes get a little threadbare over the years, the songs, too, seemed to follow a natural rate of decay. Whereas it may start out as something actually pleasant, like this:

Neil LeVang

It would soon degrade into well intentioned kitsch, if a blandly literalized interpretation. Though you can’t help but love the twins:

Otwell Twins and Aldridge Sisters

And then finally, it stumbles into full blown Las-Vegas-pills-and-booze-bloat:

Guy and Ralna

Not sure if this is the kind of education that PBS meant to provide. Let’s leave it off with some Norma to bring a little effervescence back.

— Joshua Ranger

Select Few

3 May 2011

I may regret admitting this, but from the ages of about 9 to 14 I was pretty deep into collecting baseball cards. Of course maybe I should be proud to admit it, if only to prove that I have moved beyond Baudrillard’s infantile, scatological collector’s mindset. Whatever the case, I recall that I could never get rid of any cards, no matter how many duplicates piled up. Five 1988 Topps Oddibe McDowell cards, one with a gum stain on the back? Keep ’em all and let me sort them out, in increasingly smaller piles arranged by number (first by 100s, then by 10s, then 1s…). Monetary value was one factor in my collection, but, obviously, it was not primary consideration. Just because Beckett’s Monthly categorically confirmed that those 1988 Topps were valued at 2 ½ cents for “Commons” doesn’t mean that anyone would actually pay anything at all for them.

Maybe if I had grown up in New York City I would have been more of the mind of getting rid of unwanted items by placing them on the sidewalk in front of my apartment building, as is the local tradition. I appreciate the sentiment of the practice — I can’t use this, but maybe someone else could, which is preferable to throwing it away or taking it to an overpriced “thrift” store — but I often wonder at the ideology of the situation. If you can’t use a pile of unmatched Gladware lids, do you really think they would be a great boon to someone else? And once that sweater or box of VHS exercise tapes have sat out through an overnight rainstorm, shouldn’t they just be tossed? A very odd mindset here indeed: one can’t let go enough to throw something away, but once it’s on the sidewalk, it is no longer one’s responsibility no matter how long it sits untouched.

But enough on my localized pet peeves of navigating Brooklyn sidewalks and tripping over cheap Ikea furniture. What prompted these thoughts were a couple of articles I recently read related to the concepts of selection and deaccessioning. One might say that these are some of the dirty little secrets of archiving…except they’re not dirty and they’re not secrets. Or, they shouldn’t be secrets, but they are in a way because the general public doesn’t really know what goes into the practice of archiving.

This is quite apparent in the first article I read about the investigative journalist Paul Brodeur’s feud with the New York Public Library. Seems that Mr. Brodeur donated his papers to the NYPL Manuscripts & Archives a number of years ago. It sounds as if the donor agreement had the standard stipulation that NYPL had the right to return any materials they determined to be inessential to the collection. There are a number of reasons for this kind of policy — duplication, non-original or non-unique materials, content that has no bearing on the interpretation of the collection, Xeroxes, etc. Space, staff, and storage resources are highly limited — and researchers don’t really want to dig through more than they have to — so this kind of culling is standard practice.

However, after an extended processing period, NYPL informed Mr. Brodeur that there was X percentage of papers not desired, and he could either take them back or NYPL would dispose of them. Seems Mr. Brodeur blew a gasket over this and now is using all of his connections and muck-raking powers to demand the full collection back and shame NYPL into bankruptcy and/or revising long established archival standards.

This conflict was exacerbated to a degree by the lag between ingest and completion of processing the collection (another issue, another time…), but I feel like things were at least equally exacerbated by the lack of knowledge about archival process and the emotional ties to objects one has similar to my devotion to iconography of journeyman infielders with .250 lifetime averages. I would guess that when Mr. Brodeur donated his papers, he simply emptied his file cabinets into boxes and sent them along. As we all experience, our personal files (or desk piles) are filled with important papers, but also with all the things we didn’t want to deal with at the time and then forgot about. Junk mail that got thrown in with other papers, copies of articles we read or always planned on reading, to-do lists, receipts, Chinese restaurant delivery menus…Things mingle, pile up, and, if we’re not careful, they take over physical and mental space they do not deserve.

To the creator, just as to the person who cannot trash 3-year old packets of soy sauce from old take-out, each sheet, each object is imbued with potential significance or emotional import. The archivist must have a clearer head — What level of resources are available to care for all collections? What will researchers use most? How is the integrity of the collection and of one’s profession best maintained? These decisions may seem arbitrary, Procrustean, or insensitive to those outside the process, but the decisions (should) have a strong basis in an organization’s mission statement and collection policy, best practices, subject area expertise, and various institutional factors. Articulating these issues and how they are evaluated to donors and the public should be an important opportunity for outreach and education from the archivist’s and the institution’s positions.

Which is why I was heartened to read Linda Holmes post “The Sad, Beautiful Fact That We’re All Going To Miss Almost Everything” on NPR’s Monkey See blog. Ms. Holmes has crafted an intriguing meditation on the fact that there is more cultural content in existence than any of us could ever consume in multiple lifetimes, and so this has lead to a couple of coping strategies: Culling, the act of pre-screening what one chooses to take in, and Surrender, which is more a melancholy acceptance of the facts combined with an undiminished interest in enjoying what little we can attain.

Though this post is from the user’s position rather than the archive’s position, it still touches on similar themes and considerations that we all must face as active imbibers and cultural custodians. Ms. Holmes comes down on the side of the more lyrical strategy of Surrender, but I feel that both have their uses. Accepting that not everything will be accessed or saved is important, but it is more passive in nature. Culling, which could be considered curation in a way, is an active process for shaping and maintaining collections. Archives are living entities that require active management, not stacks of papers stored in boxes waiting around just in case someone decides to browse the contents. Archivists perform highly-skilled, highly valuable duties to help make sure that our culture doesn’t surrender too much. That’s a thought worth holding onto and putting out on the street for the public to take.

AVPS Partners With METRO To Support Media Archiving

2 May 2011

AudioVisual Preservation Solutions is again partnering with the Metropolitan New York Library Council (METRO) to provide training and resources to regional libraries and archives for the preservation and management of audiovisual collections. As part of METRO’s Documentary Heritage Program, AVPS will be conducting three training workshops and will work on development of the Audio/Visual Community Cataloging toolset (AVCC), a set of guides, templates, and utilities that libraries and archives can download as a tool to assist in planning and performing a cataloging project for audiovisual materials making use of collaborative or volunteer efforts. It’s a great honor for us to support the efforts of METRO, and we look forward to working with the community they support. The full text of METRO’s press release is below and can also be found at http://www.metro.org/en/art/310/

—————————————

Through a new partnership with AudioVisual Preservation Solutions (AVPS, http://avpreserve.com), the Metropolitan New York Library Council (METRO, http://metro.org) will offer three workshops and create a pilot project to serve critical needs to libraries and archives charged with preserving and providing access to audiovisual resources. The partnership enables professional development for the library and archives community and provides greater accessibility to collections held in archives and special collections in the metropolitan New York region.

The cornerstone of the partnership between AVPS and METRO will be three workshops in June and July 2011 aimed at serving the professional development needs of archivists, librarians, and collection managers who work with audiovisual and file-based collections. On June 1, AVPS experts will lead “Managing File-Based Collections for Small Institutions” – introducing digital collection caretakers to utilities and processes that will help them perform routine archival tasks in the file-based domain. On June 16, “Using Metadata for Audiovisual Collection Management” will address how, with legacy and digital audiovisual materials, the array of technical, relational, administrative, rights, and preservation related metadata fields present a great deal of utility in the management, distribution, and monitoring of materials. On July 12, “Processing Audiovisual and Video Collections” will focus on core knowledge and skills needed to process audio and video materials for planning, budgeting, cataloging, access, grant applications, and long term storage. Details and registration for these workshops can be found on METRO’s calendar at http://metro.org.

In addition to the three workshops, the partnership also supports the creation of an Audio/Visual Community Cataloging (AVCC) tool set. The AVCC will offer a set of guides, templates, and utilities that libraries and archives can download as a tool to assist in planning and performing a cataloging project for audiovisual materials making use of collaborative or volunteer efforts. AVPS Senior Consultant Joshua Ranger notes, “The backlog of under-documented or unprocessed AV materials is one of the primary impediments to enabling access and planning for preservation. We are dedicated to finding new, cost-effective approaches to overcoming these types of hurdles and helping libraries and archives better manage collections, and we’re proud to be working with METRO towards these goals.” After initial development is complete, AVPS and METRO will be looking for libraries and archives in the region to help test and refine the tool set later this year in preparation for general release of this free resource via the METRO website.

METRO’s Documentary Heritage Program also supports work at New York University’s Tamiment Library (http://www.nyu.edu/library/bobst/research/tam/index.html) and Asian/Pacific/American Institute (http://www.apa.nyu.edu/) to document the history of the Asian/Pacific/American community in the New York metropolitan area.

“Collaborative relationships like this are essential to sustaining the important work being done by our region’s archivists and librarians,” says Jason Kucsma, Acting Interim Director at METRO. “By leveraging the expertise of consultants at AVPS, METRO is able to offer quality professional development resources to under-resourced libraries and archives that hold some of the region’s greatest treasures.”

This partnership and the services produced are made possible with funds from the Documentary Heritage Program of the New York State Archives, a program of the New York State Education Department.

About AVPS

AudioVisual Preservation Solutions is a full service audiovisual preservation and information management consulting firm. AVPS provides effective individualized solutions founded on our broad knowledge base and extensive experience in the area of collection assessment, metadata development, digital preservation, and strategic planning. With a strong focus on professional standards and best practices and the innovative use and development of technological resources, we aim to help our clients achieve efficient, high-quality capabilities to meet the challenges faced in the preservation and access of audiovisual content and institutional data.

About METRO

The Metropolitan New York Library Council (METRO) is a non-profit organization working to develop and maintain essential library services throughout New York City and Westchester County. METRO’s service is developed and delivered with broad input and support from an experienced staff of library professionals, the organization’s member libraries, an active board of trustees, government representatives and other experts in research and library operations.

As the largest reference and research resources (3Rs) library council in New York

State, METRO members reflect a wide range of special, academic, archival and public library organizations. In addition to training programs and support services, METRO also works to bring members of the New York City and Westchester County library and archives communities together to promote ongoing exchanges of information, resources, and ideas.

Why We Fight

22 April 2011

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (City, that is) recently announced the successful restoration of an audio recording of a speech Dwight D. Eisenhower gave at the museum in April of 1946. General Eisenhower’s speech was part of the Met’s 75th Anniversary wherein he was being honored for his role in overseeing the protection and repatriation of monuments and artworks during and after World War II as performed by the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Section of the allied armies (MFAA).

The audio was recorded on glass-based lacquer discs — a highly fragile format that, like most lacquer discs, is at severe risk for chemical and physical degradation. Last year the Met received a grant from The Monument Mens Foundation, an organization dedicated to honoring the work done by the MFAA and continuing to support the protection and repatriation of art works in areas of armed conflict, to preserve the audio and make it accessible to the public. Our own Chris Lacinak was very honored to be one of a group of professional advisors who provided the Met with guidance on planning their restoration.

As always, it’s great to see a successful preservation project completed, and, going beyond Eisenhower, the story and (continuing) mission of the Monuments Men is fascinating, essential history. On a personal level, however, what this story brought back to me was a memory of what a scapegoat Eisenhower was when I was growing up — the middle-of-the-road, middle-of-America, caucasian patriarch who was the symbol of the hegemonic complacency our parents were oppressed with. Perhaps an exaggerated response considering the other forms of oppression occurring in the 1950s, but for years those too-brightly-lit, kinescope-distorted, early television images of Eisenhower in close up went hand-in-hand with scenes of mushroom clouds and children ducking under desks in various documentaries or other uses of stock footage.

But then something started to happen. Saving Private Ryan and The Greatest Generation made Boomers start to reconsider their parents’ lives. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq made people think about how the military is run and the president’s role as commander-in-chief outside the emotions caused by Vietnam. Eisenhower’s farewell speech, which included the warning about the military/industrial complex, became an ur-text of liberal politics. The past from my past became a different past as the interpretive position shifted from the heat of one moment to the glow of hindsight and the heat of another moment.

The cycle of generational context would suggest that I scoff at such softening as I continue to cling to my childhood anger at the dismantling of social, educational, and arts support in the 1980s. Reagan, too, has been making a comeback of late as both sides of the aisle fight over who best represents his ideology and his legacy. Either I’m a stubborn-headed fool or this is a good sign that I’m not too old yet.

A commonality in these parallel trends is the use of audiovisual materials to support reassessments — televised speeches, recorded visits of state, audio interviews — all of it easily distributable, easily accessible content. A commonality in this commonality is that, for the most part, one can assume these recordings come from major events covered by major news outlets. This is far from an assurance that such recordings would always be preserved, but, if they were, they would be and become part of the common cultural memory. Be because of the significant audience at the time. Become because of the repeated airplay they may receive in documentaries and news stories, a situation which can create a familiarity that causes people to believe they experienced the event the first time around…which then promulgates further reiteration of the same footage, becoming a visual shorthand for wide swaths of history. To half-misinterpret the old saw about Woodstock — if you remember being there you probably weren’t.

To me, this pseudo-echo effect has two meanings. First, audiovisual content is so powerful that it can embed itself in our memory quite easily. Second, we need to dig deeper with our support of smaller local, regional, or institutional archives and historical societies in order to uncover new stories that create a fuller picture of the past. The Eisenhower recording at The Met is a great example of this. DDE’s work with the MFAA, while incredibly important, has not been a major part of the wider representation of his military and political career. Thanks to The Met and the Monuments Men, we now have a greater understanding the career and the man.

One can also look to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting’s American Archive project, which is poised to uncover loads of locally produced programming that will be highly meaningful to our understanding of broadcast history and American culture, and as equally impactful to the pleasure we derive from both. Or among some recent clients I’ve worked with, one might look to institutions like Hartwick College in upstate New York whose archives contain a treasure trove of regional oral histories and audio or video recordings from the numerous scholars, artists, and cultural figures who have spoken at the college. Or the Tenement Museum‘s extensive oral history collection of Lower East Side residents, material that can be used to support research as well as the creation of exhibits and educational material which support the Museum’s mission.

It seems so common to repeat that humans and history are complex and deserve the full picture archival material can provide. Common, but worth restating because it is so easy to take for granted that archiving just happens, that of course everyone is taking care of their stuff because it is so valuable and that all that material is easy to find and use. Archiving is more than putting items in a box on a shelf. It requires active planning, management, advocacy, and promotion. As the MFAA and the military were aware, archiving and preservation do not happen unless we make them happen, unless we enable them to happen, unless we demand they happen. I reckon they were a might good generation after all.

Azimuth Adjustment For Magnetic Audio Recordings By Audrey Young And Peter Oleksik

14 April 2011

The ease of using cassette-based media — pop it in and press play — and the development of compact, no-frills consumer electronics helped make audiovisual materials more accessible to a wider population, but there has also been the side effect of distancing users from the processes involved in recording and playback that were more apparent with open reel media and higher end decks. This is less of an issue with commercially recorded tape where standards are more regulated, but when dealing with field recordings, oral histories, and other original material, the configurations and settings of the recording device and playback device can have a major impact on audio or visual quality if unaccounted for.

In the first in a series exploring all of those knobs, switches, and buttons you see on decks, Audrey Young and our own Peter Oleksik have written a brief primer on azimuth and why it matters for archivists, researchers, and other people who listen to or work with magnetic audio recordings.

Noting Screening The Future

12 April 2011

While our own Dave Rice was presenting on a panel at the recent Screening the Future symposium in The Netherlands, newest AVPS team member Kara Van Malssen was herself on hand to participate and learn. Here’s her review of the doings that transpired:

Screening the Future

15-16 March 2011

Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, Hilversum

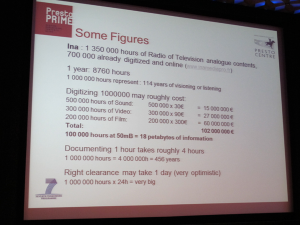

Screening the Future: New Challenges and Strategies in Audiovisual Archiving was an intensive two-day event on common challenges and solutions in the audiovisual heritage domain, held at the spectacular Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision in Hilversum. In a tightly packed schedule, 22 practitioners spoke on digitisation, workflows, digital preservation, sustainability, funding, improving access, and much more. The event marked the launch of the PrestoCentre, a new competence center for digital audiovisual preservation in Europe. A result of the successful European Presto project series (including the completed PrestoSpace and ongoing PrestoPRIME projects), PrestoCentre is a non-profit membership organization which will “provide analysis and advice to custodians and creators of audiovisual content, through online and offline services, publications and training.” There is already a wealth of useful information on their website, which is sure to grow into an indispensable resource for audiovisual archive professionals.

The conference celebrated the successful transition that many European audiovisual archives have made into the digital realm, while simultaneously sparking debate on the many ongoing challenges that these organizations still face: How can we valorize our archives? How can we fund ongoing digital preservation? How can we become more efficient? How should we approach the collection of the flood of born-digital (especially user generated) content that is not currently addressed by traditional heritage organizations? These are big questions, without simple answers.

There was quite a range of topics and speakers. However, given that it was a European event to celebrate European projects and progress, it was interesting to note that a large number of speakers were North American (or based in North America – such as the case of David Rosenthal, British, based in California). Also noteworthy was that only one woman speaker graced the stage over the course of two days (women, we can do better!). In any case, the expertise and experience of all the speakers was inspiring, and nicely balanced technical talks (like the presentation of new preservation planning tools from the IT Innovation Centre in the UK) with broad strokes.

Full presentation available here.

My personal top three presentations of the event addressed complex issues, sparked debate, and were energetic. I felt they left us with a charge, a task to improve, a direction to move toward.

———-

Peter Kaufman’s (Intelligent Television) keynote “Towards a New Enlightenment: Moving Images, Recorded Sound, and the Promise of New Technology” presented an overview of the landscape that audiovisual archives are entering as we move into the digital age, one in which audiovisual content is of equal or greater value than the textual asset (where, in fact, differences of media are evaporating altogether). Referencing Kevin Kelly’s new book, What Technology Wants, Peter whet the audience’s appetite with the notion that the millions of recorded sounds, images that archives are contributing to the web are fueling the electronic mind of the growing planetary electric membrane; we are contributing to the collective synthetic intelligence each time we give a name to an image online, or when we click a link. This global super computer is getting smarter everyday, and video is increasingly becoming part of that intelligence. With new tools like HTML5 and popcorn.js (live web citation and analysis of video content!), video is becoming a more integrated part of the web. There is enormous potential yet to come.

With that introduction, Peter offered 6 recommendations for the PrestoCentre, to help its members build together toward a “Digital Renaissance” – referencing the important recent publication by the European Comité de Sage – rather than a digital dark age. In sum:

- Engage our publics. Peter and Paul Gerhart have been working on this for the JISC-funded project, Film and Sound in Higher and Future Education. This is a marketing challenge, but one that AV archives cannot ignore.

- Engage with Technology. Make our content completely discoverable. Enabling resource discovery is a technical challenge, and involves applying relevant metadata. Users find that the range of user interfaces, search terms, and classifications make it difficult to find what they need. The commercial sector is exploiting the potential of recommendation engines (e.g. Pandora, Netflix). Can we learn from what they do? Google images can search automatically on rights embedded metadata. Wikipedia can crawl and ingest Flickr images that are Creative Commons-licensed. Peter’s recommendation: Develop a research and action plan for engaging with Google and other resources that make content discoverable.

- Facilitate use, clear rights. In order to achieve this, we must collaborate with current owners and their lawyers. Systematically set out the obstacles to making AV content available to education. Using new technology (like popcorn.js) we can actually identify rights holders, unions, and other contributors to a work, and…promote them! Give them credit where credit is due! A novel idea.

- Work with producers. Archival content begins as the point of creation. In the digital era, we can’t afford not to work with them.

- Work with business. Collectively determine best practices for public-private partnerships in AV heritage.

- And one bonus: Work with Americans! (We need your help!)

———-

Brewster Kahle’s energetic presentation, “Scaling Up, Scaling Down: Making the Most of What We Have,” on building cost effective digitization workflows and data centers for large scale digitization preservation had the audience hanging on to his every word (Brewster is certainly one of the most compelling speakers I’ve ever had the pleasure of listening to). His talk was framed around the work that has been accomplished by the Internet Archive (Millions of books digitized! The entire web archived!) on essentially a shoestring budget. Taking a bit of a jab at the Europeans, he pointed out that “large amounts of money give us excuses to not do things.” By focusing on efficiency and lowering costs, the Internet Archive is now able to mass digitize video at $15/hour and film at $200/hour. Off-air television is captured for very little, with Electronic Programming Guide and Closed Caption data extracted to improve searchability. He admits that it takes a lot of money up front to get started, but there are a number of ways to reduce costs over the long-term, such as leveraging the infrastructure of partners, and using your data center to heat your building(!). The Internet Archive measures its own progress in terms of bits in and bits out, and they are doing quite well: outbound they have 10 Gb/s of bandwidth being accessed by 2 million users each day. They are the 200th most popular site on the web, despite the fact that their “user interface is as bad as it gets.” The Internet Archive has so successfully built a cost-effective infrastructure that they can down offer cloud storage, at a cost of 1 terabyte for $2000….forever. That’s a one time payment folks.

Brewster had a lot to say about access as well. He discussed their business model, and how they are able to sustain themselves using a “free to all” access policy. He noted that, “archives make terrible business models,” and argued programs like digital lending are working, without getting the attorneys all heated up. He challenged the audience to think about their mandate as archives: are we just the preservation people, or are we the ones who are going to make stuff available on iPads? With a resounding “shame on us” he chided archives for keeping the best of what we have to offer in our basements, away from the reach of children who learn from what they can find on the Internet. We are not just archives anymore, we must be libraries too. Brewster is ready and willing to partner (for large scale data backup swaps), to offer services (digitization, storage, access), and he is going to do it cheaper and faster than most other organizations. His conclusion: “We get more done because we have less money than you.”

———-

The entire morning of the second day was a panel on “Building Workflows for Digitization and Digital Preservation,” which paired presentations from service providers (Michel Merten, Memnon; Jim Lindner, Media Matters) with representatives from some very large audiovisual archives (Daniel Teruggi, INA; Tobias Golodnoff, Danish Radio; Tom de Smet, Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision; James Snyder, Library of Congress). At first, I found it surprising that a large portion of the conference was devoted to digitization. After these talks, however, I realized that rather than a series of questions about the challenges of digitization, which has been the focus of many presentations over the past several years, these were digitization success stories: after years of trial and error, millions of hours of audiovisual heritage have been digitized. Something to be proud of, but we still have a long way to go.

Of these talks, I found Jim Lindner’s presentation on improving digitization workflows particularly useful. Jim’s simple argument is that by evaluating every point in the chain, by measuring bottlenecks, we can realized increased efficiencies. Sounds obvious, but turns out to be rarely practiced. Quite often, he finds that the problem isn’t where you might think it is, but perhaps further up the chain. Dependencies in the workflow mean you must untangle entire thing to find the problem, and then fix it.

Jim’s message is to take cues from the real world – security lines at airports, traffic, McDonalds – where efficiency is paramount. Business management and manufacturing literature can be particularly useful to the audiovisual sector. He recommended a number of books (Brussee’s Statistics for Six Sigma Made Easy, Womack and Jones Lean Thinking) but stressed that if you are just going to read one business book, make sure it’s The Goal by Eliyahu M. Goldratt’s (author of Theory of Constraints). Goldratt, and Lindner, press the need to look at the entire system, and identify the constraints, or bottlenecks. These are the places to measure things.

To illustrate the method, Jim used a typical audiovisual digitization workflow, which follows a process of accession → selection → digitization. Most archives perform selection because digitization is expensive, therefore, we shouldn’t digitize everything. But in this workflow, a backlog begins to form, and it isn’t at the digitization stage, where one might assume, but at the selection stage. Turns out, selection requires a surprising number of steps and individuals: choose tapes for selection; identify extant viewing copies, if any; generate viewing copies; view copy; catalog. If there is any bottleneck in this sequential process chain (unable to find copy, no machine to create copy), work stops proceeding. Thus, if we re-examine the overall goal, and look at the available tools to support the entire workflow, it might just make more sense to do the selection on the digital side.

———-

At the conclusion of the event, the moderator, Bernard Smith, along with Jeff Ubois, reviewed the conference themes, and asked the audience if we felt they were adequately covered. Do we know what we are preserving, and are we making the right choices? Have we developed good practices for working with the private sector? Do we have adequate funding models for sustainable digital preservation? Do we know how to best valorize our collections in today’s evolving landscape? The answer was a resounding NO. We have a lot of work left to do. Here’s hoping we’ll reconvene next year to revisit these issues and see how much progress we’ve made.

— Kara Van Malshttps://www.weareavp.com/team/kara-van-malssen/sen

AVPS Welcomes Kara Van Malssen

5 April 2011

AVPS is proud to announce the addition of our newest team member, Kara Van Malssen. Kara joins us from Broadway Video Digital Media where she was Manager of Archive Research on the Corporation for Public Broadcasting American Archive Strategy Consultancy. Kara is a 2006 graduate of NYU’s Moving Image Archiving and Preservation program, and she has held consultancies with CPB, National Public Radio, and the Museum of Modern Art, and previously worked as a Metadata and Digital Preservation Specialist in a joint project between NYU and public television broadcasters. She maintains strong interests in audiovisual preservation training and international outreach — having been invited to teach instructional sessions in Ghana, Mexico, India, and Lithuania — and also blogs on world cuisine at The Confined Nomad: Eating the UN, from A-Z, without Leaving NYC.

We have had the pleasure of working in tandem with Kara over the years on projects related to metadata development, digital preservation, and repository development, and we have always admired her skillz, strong character, outgoing nature, and wide range of personal interests. We’re extremely happy to have her join us now and look forward to the exciting opportunities ahead.

Archiving Ephemera — A Mini Manifesto (Semifesto)

21 March 2011

The lyrics for Talking Heads song “Love For Sale” were, according to David Byrne’s liner notes in Sand in the Vaseline, a not entirely successful attempt to write a love song using product or commercial tag lines. He has his own artistic reasoning behind his assessment, but from my point of view one problem is that he created a decontextualized archive of cultural information. I have plenty of peers that can cite all of the song’s references (and probably recite the entire commercial they originated from), but to my young nieces and nephews the lyrics would be empty containers that lack their purported meaningfulness. Similarly, I know plenty of 50-somethings that could recite commercial pitches from early television, and plenty of 70-somethings that can recall radio jingles and slogans from products that don’t exist anymore — all of which are meaningless reference points to subsequent generations unless footnoted in a scholarly edition of a period novel.

This begs the question of what the value is in the extensive archiving of such ephemeral, temporally-specific output. I like to think, I absolutely have to think in order to maintain momentum, that there is a value beyond kitsch or other forms of ironic re/mis-appropriation. I really hope my work is about more than saving audiovisual works with funny outfits and hairdos that people can giggle about or use in mash-ups. This is why I consider contextualization as an integral part of archiving. Despite the feelings of the general public, preservation requires a lot more than putting things online where they will “last forever”.

What, then, constitutes contextualization? There is the historical and there is the personal, and then there is where those converge. That convergence is key; neither strict historical nor strictly personal contextualizations can stand on their own as true pictures of the past. As Errol Morris suggests in his recent Times essay series “The Ashtray”, when we say that History (big H) is a social construct, we should not infer that to mean that history does not exist. It factually does. The methodology of History and the personal experience or interpretation of historical or otherwise time-based events are constructed from our own points of view and social milieu, and then degraded by the passage of time and the vagaries of memory.

The two sides establish a necessary balance between those Keatsian values of beauty and truth. History requires a degree of, not fiction — the division of fiction and non-fiction is too arbitrary and restrictive to be useful — but a degree of aesthetics or humanism. Both are truth: history is the truth of factual events and personal narrative is the truth of human experience. The context of both is required because an archive is not a resting place, but a living entity that can shift in meaning even as it does not change in content. Ephemera is not just material, but also speaks to the intangible, inconstant nature of memory, which must also be preserved.

As we lose context, we lose what ties us to the past and what moors us to humanity. The responsibility of archives to safeguard the tether to both is an essential function of what we strive to perform.

— Joshua Ranger

Noirstalgia

17 February 2011

This post was written in support of the 2011 For the Love of Film (Noir) Film Preservation Blogathon. The Blogathon is a yearly event that helps raise money to preserve a film and also raise awareness of film preservation in general. This year’s film is the 1950 noir The Sound of Fury, directed by Cy Endfield and starring Lloyd Bridges. Donations that go directly to preserving this piece of cinematic history can be made at this secure Paypal site: https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr?cmd=_s-xclick&hosted_button_id=LAWFPAB4XLHAW. And great thanks to Blogathon hosts Ferdy on Film and The Self-Styled Siren. You can find more information about the blogathon on their sites as well as links to the blog posts from all of the participants.

That said, I have to admit I had a bit of trouble deriving a topic for this post. It isn’t that the theme is of disinterest to me — rather it is of too much interest. Noir is one of those areas of obsessive deep-diving I’ve covered in my free time. As a result I’ve seen several great films, a load of mediocre films, and more than my fair share of bad and/or disappointing films. So my problem is not apathy, but more a dilemma of the omnivore, of too many treats and too much desire. (Feels like I’m sounding like a noirish protagonist here…)

Where, then, does one start in such a scenario? Well, logically and filmicly I should start with a flashback to where it all started. If I think back on it, the first noir I saw was actually Chinatown. Depending on your level of zealotry, this could be considered more a neo-noir, or perhaps a derivative heap of tripe, but whatever the case, it wouldn’t be termed a “true noir”.

Or, in a sense, it actually could be. A common noir theme is the burden of the past — characters desperately trying to escape their past in conflict with other characters desperately trying to bring it back. The ex-con that can’t go straight; the one last heist and then we’re out for good; the amour fou that cannot be the same again; the life of coulda beens that just has to be this time…

In this sense, neo-noirs like Chinatown peddle in similar obsessions, albeit in a more meta manner. The burden of the past is not isolated to the story, but also extends to the filmmaking itself in the desire to slavishly recreate angles, lighting, story arcs, mis-en-scene, and other stylistic matters, as well as the obsession with clinging to the false memory of a when men were men and dames were dames society. Neo or non-traditional noir tries to escape this burden at times as well through creative re-imaginings, recasting of roles, or the use of unexpected settings. As we know from noir, however, the harder you work to unburden the past the more you cling to it — or it clings to you.

I was going to try and be (overly) clever here and dub this concept Noirstalgia, the obsession with a past, real or imagined, that eventually destroys you and your efforts. However, upon further consideration, I’m not so sure that plain old nostalgia itself couldn’t be defined in this same way by someone like Ambrose Bierce, and I moved on from this unnecessary neologism.

What these mental doodlings did make me think, though, was, man, I really wish preservation were this simple, that all we had to do was actively work at forgetting a film and it would therefore naturally persist in order to haunt us. This got me thinking about the climax of Fahrenheit 451 where the bombs are going off and the characters are recalling — verbatim — books they had read. This scene has stuck with me perhaps more out of wonderment than anything else. I have a terrible memory for books, dialogue, lyrics, etc. I can listen to a song 157 times (Thanks for keeping track of how lamely I waste my time, iTunes!) and still not be able to recite lyrics except for a nanosecond behind real time while listening to it. The end of Fahrenheit 451 may be a powerful image, but it’s incomprehensible to me as a denouement, and I still obsess about how it could be possible.

In truth, noir is a highly stylized genre (okay, okay, if it really can be considered a genre), and cultural memory tends to work more like my own — without an immediate presence or other triggers, the materials we value so dearly are quickly forgotten or replaced by newer distractions. We have to struggle to preserve that past not so that it consumes us, but so that it is not consumed and destroyed by physical and memorial degradation. So support the efforts of For the Love of Film and of all the audiovisual preservation efforts across the globe that are required to maintain our cultural heritage so that we’re not tempted to stray back off into our dark past.

— Joshua Ranger