Article

Masstransiscope

8 October 2009

A follow up about tonight’s talk by Bill Brand at the Transit Museum in Brooklyn on his public art project Masstransiscope. Installed in 1980 in an abandoned subway station and restored in 2008, Masstransiscope basically creates a life-sized zoetrope through the interaction of the moving train and the positioning of the images, lights, and view holes.

This is a magical work of art that surprises and delights me every time I view it on the train, right up there with walking across the Brooklyn Bridge and seeing the Statue of Liberty from the Staten Island Ferry.

Bill Brand is a filmmaker, film preservationist through his company BB Optics, and a teacher of filmmaking and preservation. I caught his talk on this back in June. Entertaining and informative about the mechanics of moving image devices like zoetropes, about his process for creating the work, and about the recent preservation process. Highly recommended to check this out or some of Bill’s other work.

—Joshua Ranger

Andy Lanset Of WNYC Honored By NYART

7 October 2009

We tweeted about it last week, but it would be remiss of us to not more fully congratulate Andy Lanset of WNYC Archives for being honored with the Award For Archival Achievement by New York Archivists Roundtable. (Kudos also to the winners of the other awards, Columbia Center for New Media Teaching & Learning and Westchester County Executive Andrew Spano.)

Andy has worked tirelessly to centralize, organize, preserve and make accessible over 80 years worth of broadcast materials in all manner of formats. His efforts have reformatted and digitized a collection that spans almost the entire history of radio and that has become a valuable living resource for WYNC and other users. WNYC listeners (and listeners of stations which broadcast WNYC programs) are reminded of Andy’s contributions and the significance of WNYC’s audio archives on a regular basis. Almost no day goes by where Andy Lanset isn’t thanked and credited on air for making the amazing content held in the WNYC archives accessible for incorporation into current programs.

Andy got his start as a volunteer and then staff reporter at WBAI radio, and in the mid-80s he began freelancing with NPR as well. His work as reporter and story producer led to a greater and greater interest in field recordings and the use of archival materials in documentary pieces. This led to an increasing focus on recording, collecting and preservation work. Through his own initiative and continued pestering regarding the great importance of their collection, Andy essentially created an Archives Department and Archivist position at WNYC in 2000, which quickly grew and has become a model archive. He continues to work closely with the NYC Municipal Archives and their WNYC holdings which make up a significant portion of the older WNYC collection.

Andy’s well deserved honor reminds us of the multi-faceted aspects of being an archivist. It’s easy to get caught up in or bogged down by the technical ins-and-outs of archiving: storage, handling, arrangement, metadata (oh my!)… However, caring for a collection also benefits from a passionate advocacy for its contents. How we express our love for the content and the media. The stories we tell about the work we do. The ability to place materials in a historical and/or artistic context that all levels of users can understand. Getting across just a little bit of the enthusiasm and joy we feel about our collections and their importance can be a powerful tool for increasing support, funding, and access.

We’re not saving the world, but we’re preserving a little piece of it. Let’s hear it for Andy for doing his part to keep the tape rolling.

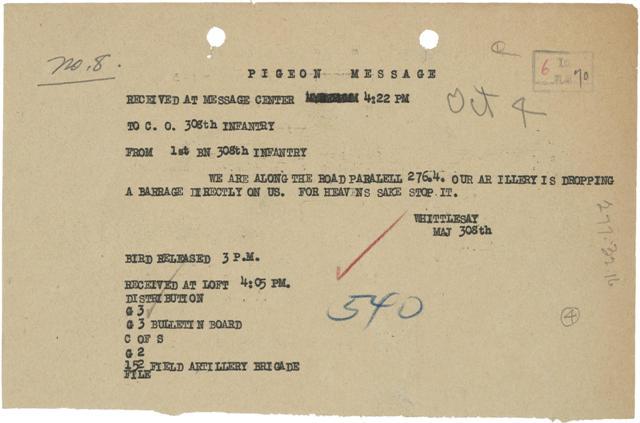

Pigeon Message

5 October 2009

From NARA’s Historical Document of the Day, transcription of a note sent via messenger pigeon during World War I — The same kind of “media format” referenced in one of our banner images. I guess they had to do an “open with” and “save as” on a typewriter in order to access the attachment.

America’s Next Top Presidential Libraries Model

4 October 2009

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) recently published their Report On Alternative Models For Presidential Libraries, an institutional review mandated by Congress to develop prospective archive models that would attempt to balance issues of cost savings, improved preservation, and increased access. (Even the big dogs have to deal with the impossible seeming task of producing more while spending less…)

Though not a light read, it does, like many of NARA’s initiatives and reports, offer plenty of tips, inspirations, or supportive arguments for preservation practices and projects. For example, the importance of “non-textual funding” for creating preservation copies of AV materials is underscored. These assets need a different kind of attention than textual materials, and consideration and funding of that “has resulted not only in better access to holdings, but also improved preservation of the original tapes” (pg. 20).

Also of note in the NARA report are sections like the one delineating proposed changes to how presidential records are processed (pgs. 25-26). Combined with the necessary review for sensitive content and the huge amount of materials suddenly available after the end of a presidency, the heavy influx of requests through the Freedom of Information Act created a sluggish response time. Searching through unprocessed folders while trying to maintain provenance and performing traditional start-to-finish processing became a hindrance to acceptable response times.

Instead, as in other archives, the implementation of a tiered system of processing prioritization has been established which takes into consideration content types. Categories such as “frequently requested,” “historically significant,” or “non-sensitive” are prioritized accordingly, thereby contributing to improved resource allocation and speedier progress.

The five alternative models to NARA’s current operational model are too specific to their history, organizational structure, and mission to discuss in depth here. Instead, three additional important points can be gleaned from NARA’s reporting process:

1. As we know too well, the continual spectre of too much work and too few resources is daunting. Strategic partnerships, pooling of resources, or repository models; exploring new areas to use assets or create access; and exploiting powerful new tools and technologies are just some of the things that should be considered in working to improve the functionality of archives and ensuring their long-term sustainability.

2. The consideration of different aspects of centralization versus decentralization is key. Just as certain audiovisual formats require a reconceptualization of the asset that separates the consideration of content from the consideration of the physical carrier, the archive itself can undergo renewed consideration from the idea of a central location to one of multiple / virtual entities. Of course, this must be accomplished while still adhering to fundamental principles of preservation. What this means is that the “virtual” needs to be understood on its own terms in order to be fully and properly utilized, just as some of the unique aspects of audiovisual archiving have needed to be understood separately from traditional paper archiving in order to apply the same kinds of standards and principles.

3. A finer point is held within Alternative Model 4 (pgs. 43-46) of a centralized archival depository where all presidential records would be maintained, unlike the current model where an archive and a museum are dedicated to a single president and those facilities are located, typically, in the president’s home state. This alternative model would involve building a new facility as well as planning and implementing a large scale digital archive for storage and access — certainly daunting, costly tasks. However, what is of note with Alternative Model 4 is that it has the largest initial cost outlay to implement but that, in the long run, it will provide more archiving jobs as costs can be reallocated from what would have been decentralized facilities, will make for more efficient access, and, ultimately, it will save more money than the alternative models offered that are less expensive at the initial implementation.

Alternative Model 4 has its pros and cons like the others, but an important lesson here is one of time. Archiving and preservation are long range efforts concerning the persistence of the past well into the future. As such, they deserve far-sighted planning and goals. This can be a difficult struggle to implement, and may not have results one sees in ones lifetime, but there are ways to model, to plan, and to advocate for the collection and for the generations to come.

— Joshua Ranger

Breaking Apart The Union Catalog — Vol. 1

29 September 2009

Google Books has been in the news a lot lately, and that inevitably prompts me to thinking about one of the main things people love and/or hate about Google: The centralization or unification of, more or less, everything. Communication, research, education, work, home, personal management, etc. It is not my place nor my interest to argue the relative beneficence or malevolence of Google. There are plenty of voices doing that, and plenty of people trying to work within or outside the system to help keep it honest. What my mind always comes back to in relation to this topic is the issue of centralization within the practice of archiving and preservation.

The advent and increase of computing tools in libraries and archives has held great promise for significantly increasing capabilities for the storage, discovery, and access of assets, whether they be digitized or not. Those of us that remember performing research projects before the widespread availability of online databases — or even before the subscriptions and portals for them became more streamlined — can attest to the partial fulfillment of this promise. There have of course been many other pushes throughout history to create a centralized repository of information or knowledge well before the digital age. The Oxford English Dictionary, the encyclopedic list of encyclopedias, national libraries, etc. We could be high-minded and discuss the human urge to organize and contain in order to deal with the uncertainties, the multiplicities, the messiness of existence. Or we could discuss it more in terms of efficiency — sure the chase of research is fun, but it can be a luxury to have the time to search so many sources and limits advancements to do work that has already been done before.

What we can say is that, though the universe tends towards decay, the human mind tends to turn away from it and back towards unity. However, we are a frustrating bunch and more often than not turn heel in the face of unity as well. I say this because, in spite of the beautiful dream of a union catalog, and despite the many well-intended and well-organized attempts over the years to create some sort of union catalog, the actualization of the dream and implementation of the various attempts have been a mixed-bag of results. At some point, the plan seems to lose steam or support or gets superseded by something else. Might this be a problem with the specific project, or might this be an inherent result of any such attempt?

Over the next few posts on this topic I will be looking at the issue of union catalogs in relation to media archives: What are some of the difficulties involved in establishing one? What other union catalogs have succeeded and what has contributed to their success? Is this an attainable idea or even a good one? And what kinds of solutions exist that archives can apply for internal use at the least, or for positioning themselves for the future? We may or may not gain a clue as to how to design and implement the ultimate union catalog, but we will definitely gain a better understanding of the process and how planning and execution relate to any project within the archive, whether large scale or not.

— Joshua Ranger

Creating Content / Creating Context

23 September 2009

Film is the great American medium. When it came along, we were still struggling to attain approval of our literary and cultural production from a withholding Europe. As an epicenter of the creation of the film industry, we were able to develop “languages” and styles that have become a major part of defining what filmic expression is. Among current filmmakers, the documentarian Ken Burns and director Quentin Tarantino could arguably be considered two of the greatest distillers of American culture within this medium, even though they take such radically different stylistic approaches. While their base approach is much the same – the consumption and reworking of archival/cultural materials – their presentational styles reflect the differences in what they are trying to accomplish. Both men work under a system of appropriation. Burns appropriates the actual materials, whereas Tarantino appropriates the aura of the materials — styles, themes, the experience associated with viewing film…

In this clip from Burns’ upcoming documentary The National Parks: America’s Best Idea airing on PBS we see his standard use of archival materials: panning across period images paired with a dramatic reading of some writing from around the same period or a commentator’s gloss on the topic:

Of course, Burns leans on the aura of the materials as well, but he is concerned with the kind of aura we typically associate with the Archive — the sense of uniqueness, of history, of a piece of the past preserved that we grasp at to try and understand but that remains not entirely tangible. Leaving any critiques of this method aside, we can see that one result of his style is the transference of the aura of the archive to his own work. That warm feeling we have towards the historical building blocks of the piece extend to the work as a whole. This is one of the great values of archival materials that more and more filmmakers are relying on — the use of items that often have less expensive licensing fees compared to commercial works but that have an immediate cache of seriousness and high culture.

Compare this then to Tarantino, especially his most recent works which have become less and less homage as their elements of pastiche have increased. Compare this clip from Jackie Brown which recalls 70s heist and exploitation films:

with the preview from Kill Bill that throws together incongruous styles from Kung Fu, Japanese crime, and Anime films (for starters):

The ultimate expression of this manner of appropriation is Grindhouse (with Robert Rodriguez and others), an attempt to recreate a very specific movie-going experience of viewing a B-movie double feature in a run-down theatre, complete with “damaged” film, missing reels, previews, and plenty of gore & sex (though you do have to provide your own broken seats, sticky floors, and disturbing odors).

In the same way Burns does, Tarantino relies on extra-textual meaning to add context/depth to his work. This is a basic tenet of art, but, depending on one’s own proclivities, Tarantino’s approach may be seen as either less significant than Burns’ (it relies on pop culture, not serious culture) or more significant than Burns’ (it relies on low culture, not more canonical historiography).

We could perhaps, then, almost consider Tarantino the more austere Archivist as compared to Burns. In our field, in trying to navigate some of the ideologies adopted from traditional archival theory of paper-based works, we deal daily with the conflict of preservation of the original item versus preservation of only the content. This issue is being pushed to the fore with the increase in the creation and preservation of digital assets. In one approach, part of preserving the original is the idea of preserving the experience — the look, the feel, the great intangible whatsit. Without content we would not have memory or history, but it is often the emotional/experiential connection to the past that drives preservation efforts. There are many reasons to preserve, and many ways to advocate for a collection. Is there a single “stylistic” approach that works?

— Joshua Ranger

Project Outsourcing: Navigating Through The Client/Vendor Relationship To Achieve Your Project Goals

16 September 2009

A guide and checklist to help clients successfully work with vendors.

AVPS Works With Library Of Congress In Developing The Library’s National Recorded Sound Preservation Plan

26 August 2009

Among the directives in Congressional legislation establishing the Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Board in 2000 are mandates requiring the Board to conduct a national study of the state of recorded sound preservation in the U.S., and to produce a subsequent National Record Sound Preservation Plan. Now that the national study is complete, Chris Lacinak, founder of AudioVisual Preservation Solutions, Inc., will assist the Library of Congress by participating in a task force making recommendations for Digital Audio Preservation and Standards. These recommendations will be incorporated into the Library of Congress National Plan for Recorded Sound Preservation.

The required recommendations will include developing a consensus on “best practice” standards in areas of audio preservation and the codification of this information for public dissemination. Areas which will be under consideration are metadata, digital preservation, digital storage and content management, and capture of analog and born digital recordings. The group is charged with formulating ideas for developing core audio metadata schemata and the tools to create and manage metadata. Consideration will be given to scalable best practice standards that can be applied to a variety of situations, including archives with limited resources. The final plan is scheduled to be completed and released to the public mid-year 2010.

We at AVPS are pleased to assist The Library of Congress and the other preservation specialists on this project.

AVPS Participating In AMIA Conference In St. Louis Nov. 4-7, 2009

26 August 2009

AudioVisual Preservation Solutions is pleased to be contributing to the advancement of archive community knowledge afforded by participation in three panels at the annual conference of the Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA) being held in St. Louis, Missouri this November.

The three sessions that we will be chairing and presenting at are as follows:

- Harnessing Collective Knowledge: Three Case Studies of New Collaborative Tools

Chris Lacinak (AVPS), Richard Wright (PrestoSpace), Mick Newnham (National Library of Australia)

A discussion and viewing of three new exciting projects – PrestoSpace’s wiki, National Library of Australia’s Mediapedia, and AudioVisual Preservation Solutions’ CEDAR – each of which provides open, collaborative, online resources that harness the expertise within the community through the use of centralized sites.

- Accessioning and Managing File-Based Born Digital Content

Chris Lacinak (AVPS), Grace Lile (WITNESS), Brian Hoffman (NYU), Dirk Van Dall (Broadway Video)

This session brings four experts and two case studies to the table to offer insights into the challenges that born digital file based video brings to your archive and offers strategies for managing it.

- Digitizing 102: Video Digitization Workflows and Challenges

David Rice (AVPS), Angelo Sacerdote (Bay Area Video Coalition), Skip Elsheimer (A/V Geeks LLC)

This session is a primer on the planning process for video digitization projects. It will examine case studies for working with damaged or ‘not-to-spec’ materials, address documentation practices for preservation workflow, and stress how to perform quality control on the process and the results.

Please join us! We hope to see you there.

For more information about the Annual AMIA Conference:

www.amiaconference.com

Comparison Between PBCore And VMD For Technical Media Metadata

29 July 2009

As posted to PBCore Resources

Introduction

VMD stands for Video Metadata and is a schema resulting from the Library of Congress AudioVisual Prototype Project. The documented schema lives at http://lcweb2.loc.gov/mets/Schemas/VMD.xsd and was last updated in 2003. From the annotation in the schema:

“VIDEOMD contains technical metadata that describe a digital video object. It is based upon metadata defined by LC. VIDEOMD contains 36 top-level elements.”

Carl Fleischhauer of the Library of Congress oversaw that activity and he reports that, in the end, the actual digitization was limited to audio and thus the VMD schema was never used by the project. He added that the community’s renewed interest in technical metadata means that this is an excellent time to revisit the topic and consider how best to document the relevant facts about video objects.

PBCore is a schema as well as a set of tools resulting from funding by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. The documented schema lives at http://www.pbcore.org/PBCore/PBCoreXSD_Ver_1-2-1.xsd and was last updated in February 2009. From http://www.pbcore.org:

“The Public Broadcasting Metadata Dictionary (PBCore) is … a core set of terms and descriptors (elements) … used to create information (metadata) … that categorizes or describes …media items (sometimes called assets or resources).”

VMD and PBCore both contain specifications for technical metadata describing video. Since these “standards” were created at different times within different environments and represent two of only a few available options this blog post offers a comparison of each of their advantages.

VMD is designed to document the technical attributes of a single video object (one video file or one videotape) to be incorporated into a METS document. A METS document may contain multiple VMD instances with structural metadata describing the relationships between them. In contrast to VMD, PBCore is designed to support documentation of multiple video objects and their structure and relationships within a single record. Given these differences, meaningful comparative analysis requires identifying the appropriate level within PBCore to compare with VMD. VMD is roughly the semantic equivalent to the PBCore’s instantiation element and sub-elements which will serve here as the level of comparison.

The objective of performing this analysis is two-fold. First, to highlight some differences that may be helpful to those considering using either one of these schemas, and second, to identify specific strengths and weaknesses, some of which may prove to be valuable points of consideration for future alteration of both standards.

So let’s begin!

Flexibility vs. Control: Man vs. Machine

The design of the PBCore XML schema definition allows for almost all of the values to be expressed as flexible text strings (exceptions to this are ‘language’ and ‘essenceTrackLanguage’ which must be expressed as exactly three letters between ‘a’ and ‘z’). This allows for a field like ‘formatDataRate’ to use “Video 25 megabits/sec”, “Video 3.6 megabytes/sec”, “25 mb/s”, “3.6 MB/s” or “26085067 bytes/second”. Although each of these PBCore values are human-readable and easily understandable, the flexibility allowed in expressing technical data makes it difficult to sort, filter, or evaluate PBCore records from different systems. For instance, if a PBCore record is evaluated to determine if an instantiation is compliant with a broadcast server’s specification, the evaluation process is challenged if one PBCore system says “44.1 kHz” and another says “44100” or one system says “4 Mb/s” while another says “524288”. The equivalent fields in VMD are used solely for the value while the unit of measurement is a fixed aspect of the value’s definition. Phrases that would be mixed into PBCore technical values like ‘ fps’ and ‘ bytes/second’ are not necessary (and not valid) in VMD.

As mentioned, VMD’s XML schema approaches technical data with more constraint. The schema constrains allowable values through validation rules to various data types like integers, text strings, or schema defined data types. The VMD equivalent of PBCore’s ‘formatDataRate’, ‘date_rate’, will not validate unless it is expressed solely as an integer. This restriction enables better interchange and forces the user to a specific manner of expressing data rates rather than stating the value in a unit of measurement within the field itself (PBCore-style).

In general VMD enables greater interoperability because of the constraints on allowable values, but in a few cases the constraints inhibit the entry of valid information. For instance ‘frame_rate’ must be an integer, so frame_rate=”30″ is valid, but frame_rate=”29.97″ is not valid. In this case, PBCore may more accurately represent technical data that requires decimal values, such as “29.97”. Within some organizations VMD has been extended to allow decimal values in place of integers.

Attributes

Both PBCore and VMD utilize XML attributes in order to augment XML data. VMD uses an ID attribute to allow unique identification of XML elements within the VMD document. Thus individual XML elements that may occur multiple times within a VMD record such as ‘compression’, ‘checksum’, ‘material’, and ‘timecode’ may be referred to elsewhere via the ID attribute value. The ID attribute serves a role similar to keys within a database. VMD also uses attributes for identification of an item as analog or digital (similar to PBCore’s use of formatDigital or formatPhysical) and for describing the dimensions of a piece of media.

PBCore 1.2.1 contains one attribute called “version”, an optional attribute to refer to the specific PBCore schema utilized. This attribute may occur within elements of type “pbcore.string.type.base” and “pbcore.threeletterstring.type.base (about half of the PBCore elements).

The use of attributes within these standards accomplishes different goals. PBCore’s version attribute potentially helps in the upgrade process of PBCore records to newer versions of PBCore since the “version” attribute can clarify which release of PBCore applies to the document. Since both VMD and PBCore have moved elements around and changed their definitions with various releases this attribute provide significant value in helping conform records from multiple sources to the current PBCore release.

The use of ID attributes in VMD allows the various elements to be related within a metadata framework. As PBCore user-feedback often points out the need for internal linking inside a PBCore document such as associating a rightsSummary with a specific instantiation or stating that this audienceLevel corresponds to that instantiation but not this one, the application of internal identifiers, such as VMD utilizes, may be worth considering in further PBCore development.

Checksums

Checksums are pertinent to the management of a digital archive and VMD provides a ‘checksum’ element that may contain ‘checksum_datetime’, ‘checksum_type’, and ‘checksum_value’. This allows VMD to document multiple checksum algorithms as applied to a digital object over time.

While PBCore’s schema and document do not directly address checksums, it is feasible that checksum data could be stored in the ‘formatIdentifier’ field (where the checksum algorithm and date is the ‘formatIdentifierSource’) or perhaps as an ‘annotation’. Since the transaction of metadata and content is a key use of PBCore and checksums validate the successful transaction, it is recommended that PBCore users determine or adopt a best practices strategy for handling checksums or that checksum management becomes a consideration of further PBCore development.

EssenceTracks and Compression

PBCore instantiation records contain ‘essenceTrack’ elements to describe the various tracks of a media object, such as video, audio, subtitle, timecode, captioning and more. In contrast VMD records do not document the individual tracks but, more specifically, the types of compression used in the file. Although VMD allows for preservation-orientated values such as ‘codec_creator_app’ and ‘codec_quality’, PBCore’s essenceTrack is more extensive with regard to technical and structural information.

formatGenerations and use

The VMD value for ‘use’ must be either ‘Master’, ‘Service’, ‘Service_High’, ‘Service_Low’, or ‘Preview’. Other values for ‘use’ would invalidate the record. For organizations that do not use this terminology this could be an awkward fit and cause semantic confusion. In contrast, PBCore’s ‘formatGenerations’ value may be any text string and provides an extensive list of suggested values at http://www.pbcore.org/PBCore/picklists/picklist_formatGenerations.html.

Summary

VMD’s XSD is much more prescriptive than PBCore for which values may be used to describe various technical aspects of video. Attractive qualities of VMD include:

• Fields for documenting checksums, their datetime stamps and types.

• Fields for documenting the encoding environment, compression quality, and tools that manage encoding/transcoding.

• Unique IDs for XML elements, enabling some linking where elements are repeatable.

• More extensive validation enables greater interoperability between systems.

In comparison to VMD, attractive qualities of PBCore include:

• A metadata structure that more closely mimics audiovisual wrappers (by the instantiation, essenceTrack and annotation elements)

• Greater degree of flexibility along with a greater capacity for data

• Extensive recommendations for controlled vocabularies

• A support system around the schema to provide information to the user on best practices, suggested vocabularies, tools to implement the schema

• And last but not least – PBCoreresources.org !

Eggs in One Basket?

It’s important as a community to figure out whether there is more value in having two standards to express technical video metadata or one. Maintaining two standards raises many issues. For instance, two issues which affect the compatibility of the two standards are:

• the scope of technical metadata

• structural relationship of the metadata’s subjects (asset, instantiation, etc)

However, both VMD and PBCore have advantages over the other in the scope of technical metadata covered by the system. In some environments increased documentation on tracks and annotations may be preferable whereas details on checksums and codec creation environments may be more relevant to another. Either of these standards could be extended to accommodate the advantages of the other (potentially PBCore could already handle VMD’s additions with the definition of best practices for their implementation).

Currently the standards are not interchangeable due to structural reasons and variances in the scope of technical metadata. PBCore is orientated to a fixed relationship between descriptive and technical metadata (a PBCore document must have at least one instantiation and an instantiation must have an asset) whereas VMD is technical only. A strategy that could harmonize these two standards could include defining the PBCore instantiation element itself as its own “mini-standard”. With this approach either VMD or PBCore could accommodate the advantages of the other standard while offering similar implementation strategies.

My hope is that this post offers some insights and generates some discussion in response to these thoughts and questions. In a best case scenario, this may result in some sort of community consensus on a path forward. In the absence of this ideal, I hope that this post offers some thoughts for consideration that will help you, the reader, make an informed decision on selecting a path that best aligns with the goals and needs of your organization.

Dave Rice, AudioVisual Preservation Solutions

thanks to Carl Fleischhauer and Joe Pawletko