Materialism, Morality And Media Culture

May 15, 2013

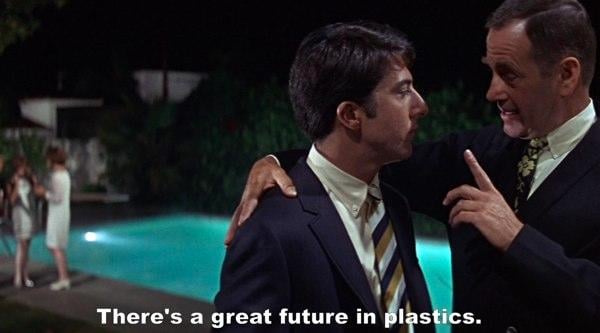

Plastics!

Film buffs know what this means. As in One Word. As in selling out one’s soul to live the life of a corporate middleman. As in a lifetime of creating cheap, soulless, synthetic replicas formed from deadly chemicals.

Film (and other media) buffs also ought to know what this means on a more physical level. As in plastics are a major component of the material object that we love. Plastic helps store the images and signals. Plastic helps transport the movements and sound through the decks and projectors. Plastic encases the hubs and reels, which themselves are often plastic.

Plastics!

So are we sellouts for worshipping plastic and chemicals, despite the warning we received from the past?

Well, apparently not so much, for it seems that digital has replaced plastics as the symbol of mass production and soullessness. In a recent blog post for Good Magazine, Ann Mack explores the analog countertrend to the digital era and decries the intangibility and inauthenticity of the digital as symbols of our fall from grace.

In Mack’s view the imperfection of physical objects makes them more real and more present to our lives than the slick perfection of digital devices. (I would ask if she has ever used a PC or an iPhone in order to review this idea…) The comparison morphs into an battle of real vs. fake. Fake is mp3s and streaming video and emails. Real is a live concert, handwritten letters, and vinyl LPs.

One could easily dismiss the gaps in logic and false equivocations as just part of the nature of blogging (I am not an unguilty party here.), but my sense is that this argument is representative of the general feeling out there around the digital vs. analog issue, as well as representative of how we conflate that issue with an assessment of cultural trends and moral judgement.

When we talk about our love for media there are three possible aspects we are referencing: the materiality and mechanisms of the physical object, the characteristics of the format that present themselves during playback, and the content itself outside of the object/format. One or many of these factors may be an influence on the viewer depending on their level of knowledge and engagement.

For those of us deep in the audiovisual production and preservation field this separation may not seem right. If we love one portion, shouldn’t we love them all for working perfectly in concert to create an experience? Love them all despite their flaws and physical or intellectual failures. And fail media does. Often. Often and often spectacularly.

But the complete formation of this golden triangle is seldom the case. This movie is awful but it was shot and distributed on VHS, so that makes it more interesting…This independent movie overcomes the flaws of how it was produced due to the performances and story…This movie is a minor classic but we’re seeing it projected on a nitrate print so that elevates it…This home movie is amazing but the original was so shrunken that it’s full of gaps and poor image quality…

Really though, these issues are incredibly academic and trend-based in nature. Delving down to that level requires an extreme knowledge and experience with film history that many people would not care about, but it is also linked to shifts in what a cultural moment considers valuable and relevant. This shifts back and forth from the new to the nostalgic, from the analog to the digital — though not all formats are considered equally within their respective categories (audiocassettes have a minor nostalgic following but will never be as respected as vinyl).

I find it interesting that the arguments Mack makes are largely about the experiential — the album cover, feeling paper, face time — and seem to mirror the studio arguments in the 50s on the superiority of the theatre experience over television. In either case this is a facetious argument because the format or experience is not a telling factor of the quality or purpose of the content, but more the individual’s reason or ability to select one experience over the other. A banal handwritten letter is still a banal letter. A film projected on a screen does not necessarily gain in aesthetic or intellectual quality purely due to that occurrence, or the fact that you were eating Goobers while watching it. (But, then again, Goobers.)

But this area of the format wars seems well trod and is not where my interest here lies. To chase a trend in order to explain it seems as frivolous as chasing trends to simply follow them. What I am concerned about is the moral judgement that this analog/digital divide gets saddled with. About the link of authenticity to physical media, to imperfection, and to time away from the screen as Mack puts it.

In and of themselves these are not bad things to be interested in, and neither are their opposites. Where I have a big question is whether we have been tricked into having an argument over the superior format of consumerism and branding. In Mack’s blog the positive examples are about growths in revenue and materialism. Does it really matter if one is purchasing a typewriter or a computer, a DVD or a movie ticket? And what about the moving line of nostalgia? Typewriters are old and cool, but it’s still mechanical and not handwritten. VHS was feared as the death of film, but now, perhaps because the threat was averted, it’s got more cache via nostalgia than DVD or streaming. Do the qualities of a material need to be perceptible to be of value (the grain of film, the touch of paper, the whir of the projector)? These sensual events do have meaning and value, but why is that more important than the intangible, indescribable, or worse, the inconvenient facts of materiality?

In the end, yes, the relative availability of formats or content is market driven, and that has an impact on our ability to preserve materials. But I wonder what happens when we internalize consumption as a point of advocacy or a valuative argument, and then merge that with the moral judgements we make on what and how other people consume. What does that do to our critical faculties, to what we are willing to accept or reject, to latch onto or overlook in our assessment and decision making? And do the results of that force us into a moral rigidity when we need to be much more plastic?

Plastics!

— Joshua Ranger